Iraq War: Not a mistake, but a Holocaustic crime

By Ben Tanosborn

Either our minds have softened in the United States, or our hearts have hardened way beyond the callous stage. Or, likely both!

Just 13 years past his criminal decision to invade Iraq, George W. Bush is campaigning in South Carolina to get his younger brother, Jeb, in the White House. A fitting payback by an illegitimate and unworthy former president to return Jeb’s intercession as Florida’s governor in America’s mishandling, comical if it hadn’t been for the eventual very tragic consequences, of the 2000 presidential election. It might be worthwhile to remember that it was the US Supreme Court that basically decided to put George Bush, and not Al Gore, in the White House in a 5-4 decision eloquently, but incorrectly, authored by the just-deceased and widely admired justice, Antonin Scalia.

Time and time again we, Americans, keep referring to the invasion of Iraq in 2003 as a mistake; almost in unanimity: Democrats and Republicans. But it was not a mistake, not by a long shot! It was a calculated, belligerent act by a government clique of elitist war-hawks, Bush-Junior and Dick Cheney at the top of the criminal heap. Fortunately for these American leaders, and unfortunately for the rest of us, only leaders from nations vanquished are indicted and go to trial. If the Axis had prevailed in World War II, and we were living in Hitler’s Millennium, there would not have been those Nuremberg Trials (1945-9), or the subsequent enactment of important, critical international law, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), or the Geneva Convention (1949). No, no gallows for Bush and Cheney… only admiration from fools!

We, as a nation, need to stop calling Bush’s Iraq-deed a mistake, and stop minimizing the holocaustic repercussions of such idiotic, ill-conceived criminal behavior. We should visit and revisit the consequences, if for no other reason than to learn or relearn; and keep George Santayana’s dictum alive: Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. And Bush’s decision was no venial sin, not just “a mistake”… and its disruptive consequences have proven to be grave and lasting.

US’ unnecessary and irrational post World War II meddling in the Middle East, helping the anachronistic Shah of Iran (1967-79) as the zenith of geopolitical stupidity, was only topped by lack of peripheral vision in international politics from a far from lucid George W. Bush… given credit by some (perhaps many) claiming “he kept Americans safe.” Yes, George (Santayana, not Bush); stupidity reigns supreme and history, unfortunately, recycles in a circle in this United States of America.

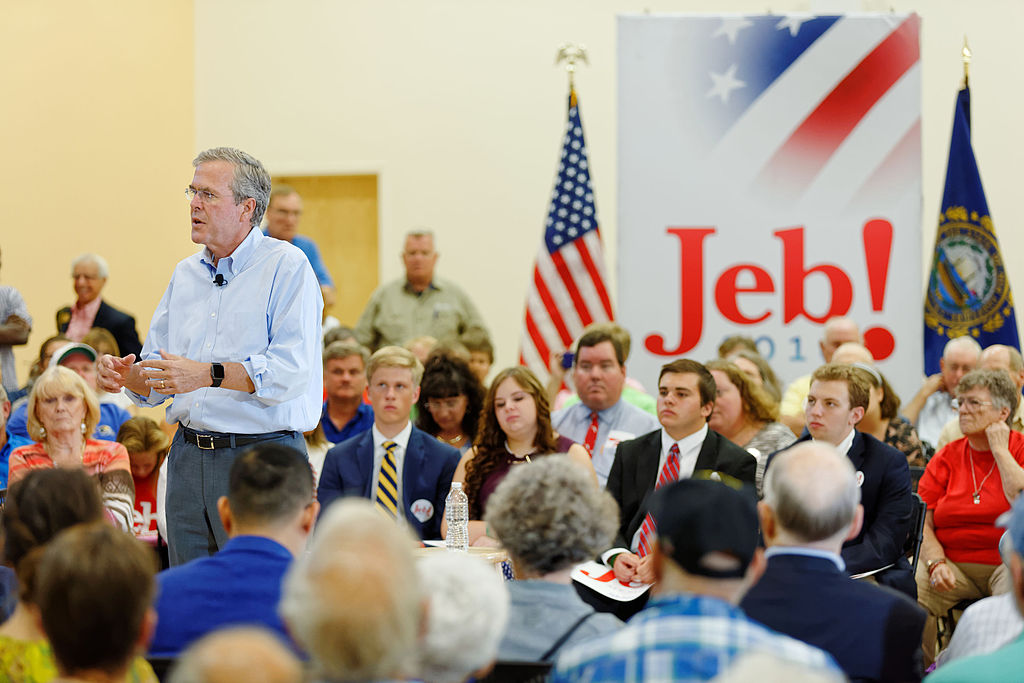

Bush-43’s new mission of the sibling-type, the election of Brother-Jeb, just like the other mission, Iraq, is only likely to become accomplished once again atop an aircraft carrier, but not at the polls; people (a definite majority) have had it with the Bush brand.

And, that same resolve is beginning to take hold in the Democratic electorate with the Clinton name. Hillary’s recitals of smartness-by-association with the likes of Obama, Henry Kissinger and Madeleine Albright may not bring her the credentials she is after. After all, Kissinger’s policies can be directly associated with the death of countless millions of innocent civilians in Cambodia-Vietnam; while Albright’s conscience should weigh heavily with the death of hundreds of thousands of Iraqi children.

Just a side note for Donald Trump and his legion of birthers: Wouldn’t it make sense to advocate “purity” in US’ presidential succession, making sure that the top 5 positions in government (maybe more) are filled by natural born citizens? The position of Secretary of State comes to mind as fourth in line (after the Vice President, the Speaker of the House, and the President pro-tempore of the Senate) which would have disqualified those two foreign born politicians, Henry Kissinger (Germany) and Madeleine Albright (Czech Republic) from becoming president.

Yes; Hillary Rodham Clinton, former First Lady, Senator and Secretary of State constantly invokes her extensive experience in affairs of state as strongly qualifying her for the White House; yet her vast experience follows for the most part decisions with bad judgment… bad experience which in my book is counterproductive to that required from a prospective good and effective leader. Two superbly flawed American dynasties or dynasties-wannabe: Bush-es and Clinton-s; yet, most Americans hold admiration for one or the other when both probably deserve to be flushed down the historical toilet.

Go figure!