Why Trump’s tax cut is not working

By Arthur S. Guarino

The Trump Administration and Republican Congress were enthusiastic about a tax reform package that would not only pay for itself, but increase government revenues due to a rising American economy and decrease budget deficits. The expectations have fallen far short and the tax cuts could actually spell trouble for the American economy.

When Donald Trump ran for president, he promised a growing American economy through tax reform and cuts in tax rates for individuals and corporations. With the backing of a Republican House and Senate, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) became law in December 2017 and went into effect in January 2018. The expectation was that the act would simplify the United States tax code, lower tax rates for households as well as large and small businesses, and see government revenues increase by spurring growth in the American economy. This has not occurred as planned and the Federal budget deficit has drastically increased along with the national debt while the American economy has not shown the Trump Administration’s promised 4 percent growth rate. Now the key question is: What went wrong?

What the TCJA was supposed to accomplish

The TCJA was designed to make changes to both personal and business taxes. With regard to personal taxes there were major changes. The standard deduction was increased for married couples from $12,700 to $24,000 while single filers saw the deduction go to $12,000 from the old $6,350. This may cause more families to use the standard deduction over itemized deductions in the future. However, the personal exemption was eliminated under the TCJA which was a $4,050 deduction per taxpayer and dependent.

Another major change was that the Child Tax Credit went from $1,000 to $2,000 for each child under 17 years of age and that $1,400 is refundable with a $500 credit per other dependents. Under the TCJA a single filer taxpayer can receive the full credit if their income reaches a maximum of $200,000 and $400,000 for joint filers. A big change under the tax act was that the deduction for state and local income tax, sales tax, and property taxes, otherwise known as the “SALT deduction” was capped at $10,000. Prior to TCJA, there was no ceiling for the SALT deduction and for states that have high property taxes such as New Jersey, Massachusetts, and California, this deduction was a significant relief for homeowners.

Another major change was the estate tax. Under the old law, a single person’s estate over $5.6 million was taxed at 40 percent. But under the new tax law, only estates over $11.2 million will be subject to the 40 percent tax while for married couples who combine their exemptions, their estate will incur the same rate if the estate is above $22.4 million.

The TCJA reduces the impact of the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) since the exemption level for married taxpayers filing jointly was increased from $84,500 to $109,400 and for single filers the amount increases to $70,300 where it was previously at $54,300.

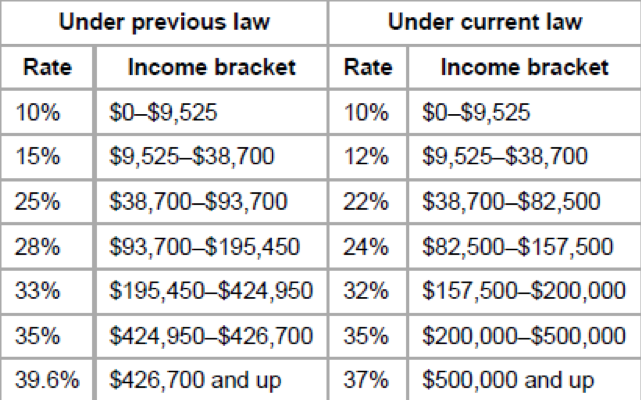

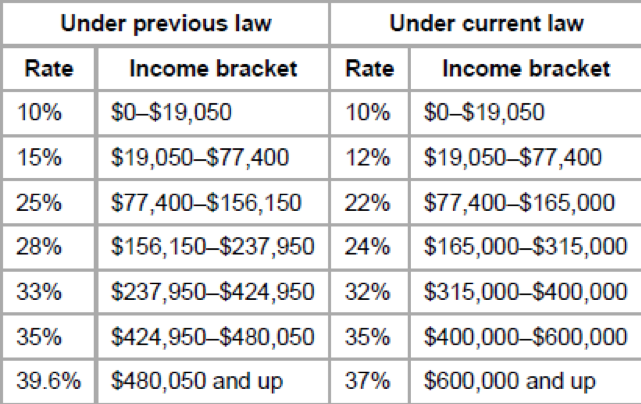

But perhaps the biggest change to the personal tax structure has been alterations to the single and married filer’s tax rates. For single taxpayers, the top or marginal tax rate under the old law was 39.6 percent but it has been changed to 37 percent. This also includes the new tax bracket for the marginal tax rate of 37 percent increasing to $500,000 while before it was at $426,700. Also, the tax rates have been reduced to 12, 22, 24, and 32 percent covering lower income brackets. For those married and filing jointly, the marginal tax rate is 37 percent which is reduced from 39.6 percent. The new tax bracket for the marginal tax rate of 37 percent increases to $600,000 while under the old law it was $480,050. The new law also has reduced tax rates of 12, 22, 24, and 32 percent.

There has been changes in the tax laws for businesses. A key change in the tax law was the repeal of the AMT for large corporations. The basis for the AMT was to ensure that large companies would not use multiple deductions in order to avoid paying their share of taxes. The TCJA did away with the corporate AMT altogether so that any and all businesses could take as many tax deductions as legally possible. The repeal of the corporate AMT covers large corporations, midsize businesses, and small firms.

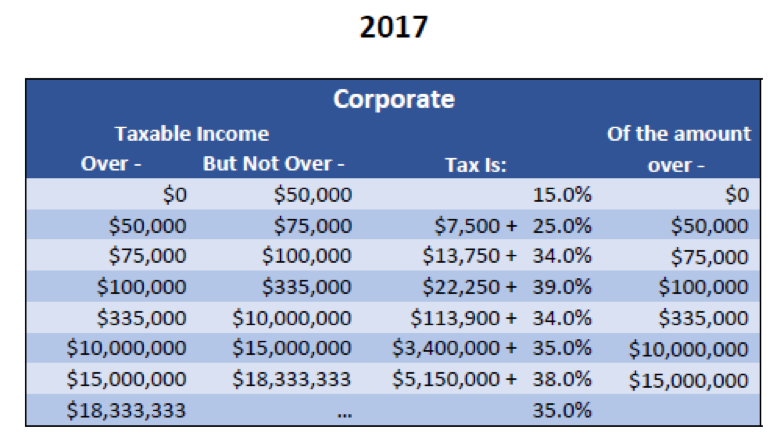

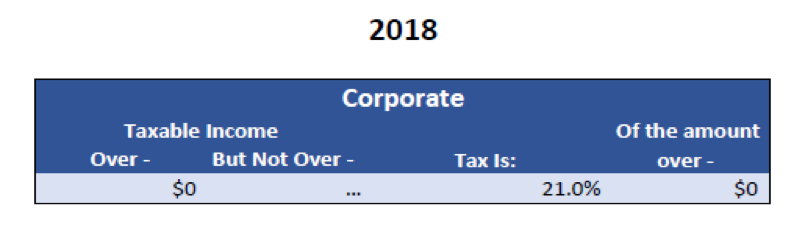

Another key change in the new tax law is a rate reduction for C-Corporations or C-Corps. A C-Corp is set up so that it is a separate and distinct legal organization from its owners. A C-Corp is set up to be a profit-making enterprise, have its own legal liability as a separate entity, and enjoys separate taxation from its owners. However, C-Corps can be taxed at both the corporate rate and the personal income tax rate if corporate income and payments are given to its shareholders. Under the TCJA, C-Corps now enjoy one, flat tax rate of only 21 percent rather than a possible high of 35 percent. This makes calculating a C-Corps tax liability much easier and provides for better financial planning.

Under the TCJA, corporations having international subsidiaries will receive favorable treatment for foreign income. Many American multinational firms have managed to send substantial sums of money overseas into foreign tax havens and thereby postpone paying income taxes on their overseas profits for an indefinite period of time until the cash was brought back to the United States. Under the new tax law, American companies could bring their profits earned overseas back to the United States at a 15.5 percent tax rate for cash and equivalents while also having an 8 percent rate for reinvested earnings. This allows companies the opportunity to bring their foreign earnings to the United States and enjoy minimal tax liability.

A key beneficiary of the TCJA are pass-through business owners such as partnerships, S-Corporations, and sole proprietorships. As a pass-through business, the firm’s earnings are taxed at the owner’s individual tax rates and under the old tax law this could be as high as 39.6 percent. Under the TCJA, there is a 20 percent deduction for pass-through income and the earnings for a pass-through business is now reduced to 29.6 percent but the benefit is reduced when earnings reach $315,000 if married and filing jointly and $157,500 if single.

The key provision of the new tax law is that the corporate tax rate has been reduced to a flat 21 percent from a high of 38 percent on a graduated scale. This is perhaps the most important aspect of the new tax law since corporations now will have a much easier time calculating their tax liability.

Why the TCJA is not working

While the TCJA was intended to cut taxes, help the federal budget, and reduce the national debt, the exact opposite has occurred.

First, the intention with the TCJA was to not only cut taxes for all businesses but also simplify the estimating and planning for a firm’s tax liability. Under TCJA, the calculation for a firm’s tax liability went from a long-used graduated tax scale to a simple flat 21 percent tax rate. While on the surface this may seem a step in helping a company estimate its tax liability, this actually depends on the size of the taxable income. For example, if a company has taxable income of $12 million, under the old tax law its tax liability would be $4,100,000 with a tax rate of 35 percent. But with the tax rate of the TCJA at a flat 21 percent, the tax liability is $2,520,000. For a firm this large, the tax savings is substantial. However, if the company is much smaller or just getting off the ground and has $65,000 in taxable income, under the old tax law it would be in a 25 percent tax bracket with a tax liability of $11,250. But under TCJA, the company would actually pay more at $13,650 under a flat 21 percent rate.

If company had $45,000 in taxable income, under the old law it would pay $6,750 at the base rate of 15 percent. Yet, under TCJA its tax liability under a 21 percent rate would be $9,450. Based upon calculations for various size firms in terms of their taxable income, larger firms with taxable income in the millions will actually see smaller tax liability under TCJA. However, smaller companies with taxable income at $90,000 and below will actually see an increase in their tax liability as opposed to the previously used tax plan. This is actually unfair to smaller businesses and individuals looking to start their own companies. Rather than help small businesses lessen their tax liability or assist them when times are tough, the TCJA actually hurts their ability to exist.

With regards to the federal budget, the situation looks quite bad under the TCJA. According to the United States Treasury Department, the federal government had a budget deficit of $310 billion in the period between October 2018 to January 2019 versus $176 billion for the same time a year earlier. The Treasury Department reported that for the period of October 2018 to January 2019, the federal government had expenditures increasing by 9 percent or $115 billion while total receipts went down $19 billion or 2 percent due to reduced business and individual income tax receipts. For the year 2018, revenues for the federal government went down 1.5 percent and spending increased 4.4 percent. The problem here is the rise in the federal budget deficit for 2018 to $913.5 billion. The problem is that the Trump Administration promised that tax cuts under the TCJA would pay for themselves and that with a growing macro-economy federal receipts would rise. This has not occurred and there has not been any increase in government revenues after the TCJA went into effect. According to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, there has been revenue losses between the years of 2017 and 2018. They stated that individual income tax revenue is basically unchanged from 2017 and total nominal revenue decreased 4.3 percent, with real revenues down 6.4 percent, and revenues as a share of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP) saw a drop of 8.8 percent. In sum, government revenue has seen a substantial decrease since the passage of TCJA. In the long term, the situation will actually worsen. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, under the TCJA the year 2026 will see government revenues come to 14.1 percent of GDP, which will fall far short of projections by the Trump Administration of 18.2 percent.

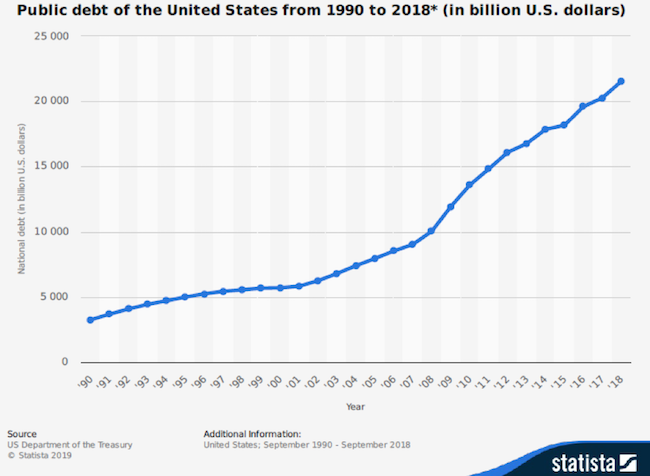

The TCJA will also hurt the national debt, in the short and long term. The national debt has gone from $20.244 trillion when Trump took office in 2017 to over $22 trillion in 2018. However, the situation will continue to worsen in the long run. The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimates that there will be $1.46 trillion increase in the national debt over the next decade. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) stated in April 2018 that the TCJA would increase the national debt by $2.289 trillion over the coming decade. The worst-case scenario is provided by the Tax Policy Center (TPC) in their analysis of the Trump Administration’s tax plan. The TPC has projected that the national debt will increase by $1.475 trillion in 2019 and by $2 trillion to $7 trillion by 2026. This will worsen the national debt and make the macro-economy a very bad situation if GDP does not increase accordingly in the next decade. The TPC estimates that the debt to GDP would rise to 25.4 percent by 2026 and increase to 49.9 percent in 2036.

Tax relief: At what cost?

While many Americans and financial analysts call for tax relief, the key question is: At what cost? The TCJA is now law, but it should be reconsidered in the future if the economy is not growing, the federal budget deficit is growing higher than projected, and the national debt is seeing phenomenal increases to the point when the interest payments will surpass paying for Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security combined.

*This post contains affiliate link(s). Click here for Affiliate Disclosure.