By Marján Attila and Szuhai Ilona

Is our global humanitarian system in transition? If so, what are the key issues before the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit

“Today’s needs are at unprecedented levels and without more support there simply is no way to respond to the humanitarian situations we’re seeing in region after region and in conflict after conflict.” António Guterres, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees

Introduction

The world is preparing for the World Humanitarian Summit. The United Nations will host the event in Istanbul, in 2016. Before the meeting, regional consultations are held in several parts of the world hit by humanitarian crises. Expectations are high. The study forecasts how the EU can financially contribute to donor activities in the future taking into account the fact that there are too many humanitarian crises.

Recognising that the humanitarian landscape has changed tremendously over the past few decades, the UN Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon initiated the World Humanitarian Summit (WHS) as a three-year initiative which will set the scene for a wide-ranging international discussion on how to adapt the humanitarian system to the new reality so that it serves the people in need more effectively.

The WHS has a two-fold objective:

1) secure commitment to a strategic agenda which makes humanitarian action fit for the challenges of 2016 and beyond;

2) develop stronger partnerships and seek innovative solutions to persistent and new challenges so that the agreed strategic agenda is implemented after the Summit.

As Jemilah Mahmood − Head the WHS Secretariat at the UN Headquarters in New York – stated, “Now more than ever, we need to recognise the sheer magnitude of the problems we face in the humanitarian and developmental sectors, and focus our collective resources on solving them.” The WHS is an opportunity for governments, the UN and intergovernmental agencies, regional organisations, non-profits and civil society actors, the private sector, academia as well as people affected by crises to come together, take stock of humanitarian action, discuss the changing landscape, share knowledge and best practices, and chart a forward looking agenda.

Before the Summit, through a two-year consultation process, the aim is to build a more inclusive and diverse humanitarian system by bringing all key stakeholders together to share best practices and find innovative ways to make humanitarian action more effective. The process is being managed by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). The European Commission’s Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection Department (ECHO) is taking an active role in contributing to the discussion throughout the entire WHS process.

The following agenda for consultations have been established:

- West and Central Africa − Côte d’Ivoire, 19-20 June 2014;

- North and South-East Asia − Japan, 23-24 July 2014;

- Eastern and Southern Africa – South Africa, 27-29 October 2014;

- Europe and Others − Hungary, 3-4 February 2015;

- Middle East and North Africa − Jordan, 3-5 March 2015;

- Latin America and the Caribbean − Guatemala, 5-7 May 2015;

- Pacific Region − New Zealand, June 2015;

- South and Central Asia − 3rd Quarter 2015;

- Global Consultation − Switzerland, October 2015.

Consultations will engage a broad range of partners, including people from affected territories, humanitarian actors, technical experts and the public through the WHS web platform. The key findings from both the regional and online consultations will be included in the final report of the Secretary-General that will set the summit agenda and influence the future of global humanitarian action.

Change is needed in the international humanitarian system as almost 25 years after UN General Assembly resolution 46/182 created the present humanitarian system – around the ERC, the IASC and a set of established core and guiding principles – the landscape of humanitarian action has changed considerably. Inter-related global trends, such as climate variability, demographic change, financial and energy sector pressures or changing geo-political factors have led to increased demand for humanitarian action. This focuses around three types of humanitarian realities: armed conflicts, disasters caused by natural hazards, and ‘chronic crises’ where people cyclically dip above and below acute levels of vulnerability. Each scenario has its own characteristics and challenges.

In response to the challenges, humanitarian actors have sought to improve their services and maximize their impact on people in need. In particular, the 2005 Humanitarian Reform and more recently the IASC Transformative Agenda developed new approaches to working more accountably, predictably and effectively, and discussions to update international humanitarian legislation take place each year in the General Assembly. But there has been no collective exercise to take stock of the achievements and changes that have occurred since the current system was formed. Nor has a structured dialogue taken place between the four major constituencies that contribute to humanitarian action today: Member States (including affected countries, donors and emerging and interested partners); the global network of humanitarian organizations and experts; associated partners, (including private sector, religious charities, etc.); and, affected people themselves – as first responders, communities and civil society organizations, to think through how to address the current challenges. While the fundamental principles enshrined in General Assembly Resolution 46/182 will continue to guide our work, we need to explore how to create a more global, effective, and inclusive humanitarian system.

The Summit hopes to engage states in commitments to a new range of global humanitarian policies and financing. The main aim of the Summit is to: “set an agenda to make humanitarian action fit for the challenges of the future, by broadening and deepening partnerships for those in need.” The Concept Note that is guiding consultations running up to 2016 has put innovation right at the centre of its work, and is focusing on four main themes: humanitarian effectiveness; reducing vulnerability and managing risk; transformation through innovation, and serving the needs of people in conflict.

Humanitarian crisis

According to Humanitarian Coalition, humanitarian crisis is an event or series of events which represents a critical threat to the health, safety, security or wellbeing of a community or other large group of people, usually over a wide area. Armed conflicts, epidemics, famine, natural disasters and other major emergencies may all involve or lead to a humanitarian crisis that extends beyond the mandate or capacity of any single agency. Humanitarian crises can be grouped under the following headings: Natural Disasters (earthquakes, floods, storms and volcanic eruptions). Man-made Disasters (conflicts, plane and train crashes, fires and industrial accidents). Complex Emergencies (when the effects of a series of events or factors prevent a community from accessing their basic needs, such as water, food, shelter, security or health care). Complex emergencies are typically characterized by: extensive violence and loss of life; displacements of populations; widespread damage to societies and economies; the need for large-scale, multi-faceted humanitarian assistance; the hindrance or prevention of humanitarian assistance by political and military constraints; significant security risks for humanitarian relief workers in some areas.

The causes for a crisis are always context-specific and each crisis is different. Humanitarian crises usually require a multi-sectoral response. Complex emergencies pose many challenges to humanitarian actors, including access to vulnerable populations, human rights abuses and the possible presence of armed actors.

Do we live in a safe or dangerous world?

Humanitarian crises in the world today − Syria, Iraq, Central African Republic, South Sudan and now Gaza − all demand immediate and massive humanitarian response. The crises are not only large-scale, affecting millions, but the conflicts also are complex, each with unique political realities and on-the-ground difficulties. They are not alone among crises competing for our attention. They are simply the biggest, pushing off the front pages other crises where human needs remain urgent: Darfur, Central America, Pakistan, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Somalia. The question is obvious: Do we live in a safe or dangerous world?

During 2012 − the most recent year for which there are data − the number of conflicts being waged around the world dropped sharply, from 37 to 32. High-intensity conflicts have declined by more than half since the end of the Cold War, while terrorism, genocide and homicide numbers are also down. And this is not simply a recent phenomenon. According to a major 2011 study by Harvard University’s Steven Pinker, violence of all kinds has been declining for thousands of years. Indeed Pinker claims that, “we may be living in the most peaceful era in our species’ existence.”

Over the last decade, claims that the number and deadliness of armed conflict has declined since the end of the Cold War − while not uncontested − have become increasingly accepted. The most telling finding is that the number of high-intensity state-based conflicts − those that kill a thousand or more people a year − has declined by more than half since 1989.

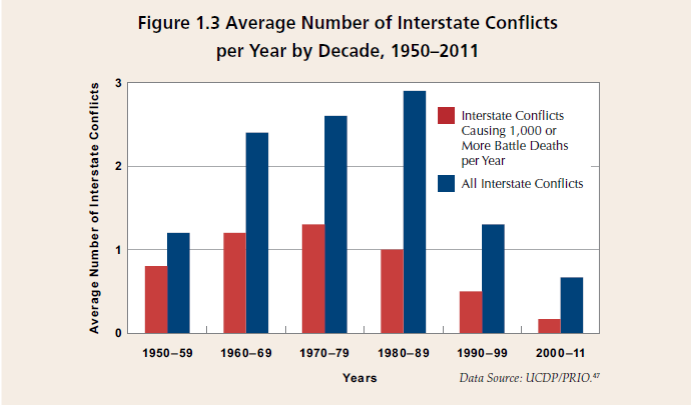

Conflicts between states − especially high-intensity conflicts − have become very rare since 1989. There has been less than one interstate conflict per year on average since 2000, down from almost three during the 1980s. Since the end of the 1990s there has been a growing – and increasingly heated – debate over recent and longer term trends in violence around the world. Proponents of what has become known as the “declinist thesis” argue that violence has declined; others accept the basic “declinist” thesis but challenge the explanations that seek to account for it. But while large-scale organized political violence has declined over the past quarter of a century, some analysts argue that organized – and often transnational – criminal violence has increased. In fact, death rates in some countries exceed those in the deadliest wars currently being waged around the world.

The rise of transnational organized crime is part of what has sometimes been described as “the dark side of globalization.” But the increase in global trade, investment, and other forms of transnational economic integration has also been associated with increased levels of human development, wealth and global freedom. Globally, the number of conflicts had been stabilising at a relatively high level. However, because today’s conflicts are mostly low in intensity, global battle-death tolls have remained relatively low – despite a slight increase from 2010 to 2011.

High-intensity conflicts have fluctuated at a relatively low level for most of the 2000s. The six high-intensity conflicts active in 2011 were located in Afghanistan, Libya, Pakistan, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen. Some of these conflicts have been active, and among the most deadly, for many years. Only one of the high-intensity conflicts mentioned above – that in Libya – was directly related to the Arab Spring. The wars in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Somalia, and Yemen were associated with ongoing international and local campaigns against Islamist group while the violence in Sudan was mostly related to the events surrounding South Sudan independence, and, to a lesser extent, to continuing problems in the Darfur region.

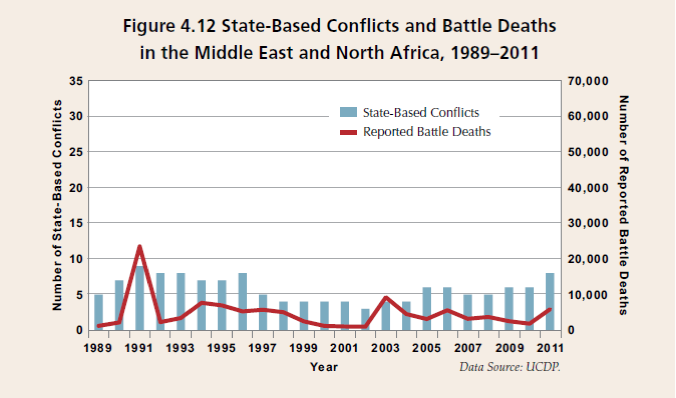

Most state-based conflicts today are intrastate conflicts, which are fought between the government of a state and one or more non-state armed group over control of government power or a specific territory. Many of the high-intensity conflicts in 2011 – such as the conflicts in Afghanistan, Somalia, and Yemen – were civil wars in which troops from other states participated in the conflict in support of one or more of the warring parties. On the other hand, in recent years, the Middle East and North Africa – the second-most-deadly region in 2011 – saw reported battle deaths triple, going from under 2,000 in 2010 to almost 6,000 in 2011. Part of the reason for this increase can be attributed to the events related directly and indirectly to the Arab Spring.

The number of conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa increased by two in 2011 with conflict onsets in Libya and Syria that were both related to the Arab Spring. Battle deaths in this region also increased in 2011. In addition to the Arab Spring conflicts in Libya and Syria, the increase was a result of the escalation of ongoing conflicts in Yemen, Iran, and Turkey.

Researchers studying the Long Peace of the post-World War II period have identified growing international economic interdependence – manifest in the dramatic increase in international trade and foreign direct investment – as one important disincentive for interstate war in this period.

Conflicts between states, as well as those between states and rebel groups, tend to dominate war-related news headlines. Most people’s understanding of the incidence of armed violence around the world comes from the media. But media reporting – not surprisingly – focuses on bad news. Violence makes headlines – its absence does not. For the past two years world attention has focused on the escalating violence between Bashar al-Assad’s regime and armed opposition groups in Syria.

Too many humanitarian crises challenge the sources and capacity

Kristalina Georgieva, EU Commissioner for International Cooperation, Humanitarian Aid and Crisis Response, warns that there is “no light at the end of this tunnel: we must get used to a ‘new normal,’ where we face multiple challenges with finite resources.” We need to accept the reality of not having enough money to respond. With so many crises, the tendency is to focus on the latest and the “biggest” crises. A “crisis of the month” mentality has been replaced by “crisis of the week.” Numbers matter, so understandably our focus is drawn to large-scale crises. When hundreds of thousands of refugees flee a country, we respond. When smaller numbers are displaced by, say, a storm on a Pacific Island – even when proportionally a greater percentage of the population is affected − we tend to overlook it. A few years ago the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies reported that 90 percent of all natural disasters have fewer than 50 casualties; numbers not sufficient to mobilize an international response but no less devastating to those affected. Too many crises have consequences. In 2012 the worry was how the international community would come up with the resources to meet humanitarian needs in Syria, estimated at $1 billion a year. Today, the appeal for Syria is over $6 billion with less than 25 percent funded by mid-year. Syria is far from the only crisis for which urgent appeals for funding are made. South Sudan, Central African Republic and Gaza are all desperate situations that need a robust international response.

Too many crises also increase the demand for experienced staff. Humanitarian agencies find it daunting to maintain adequate stand-by capacity to respond to a wave of major disasters. Stand-by rosters are stretched. An overwhelming number of crises make it almost impossible for the international community to respond well − or even adequately − to the existing humanitarian disasters, much less to prepare for future ones. Humanitarian crises are influenced by political problems; the inability of our international political system to resolve these crises is stunning. The Responsibility to Protect populations from genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing has emerged as an important global principle since its adoption by the UN World Summit in 2005. The fact that there are too many humanitarian crises today is the result of a failure in global governance. Change is needed in the international humanitarian system and perhaps the World Humanitarian Summit in Istanbul in 2016 will provide an opportunity for fresh − and even radical − thinking about the way the system responds.

The Brookings Institution assessed the global response to humanitarian crises. Throughout 2013, international humanitarian actors have faced major challenges responding to conflicts and natural disasters across the globe. Tens of thousands of people died in Syria and millions were displaced while international actors struggled to get access to desperate people. While escalating violence in such diverse countries as South Sudan, Iraq, Yemen and the Central African Republic may have received less media attention than Syria, these situations also posed particular challenges to the international community. At the end of 2013, the international community was mobilizing a major relief effort to respond to Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines, a storm that affected more than 14 million people and displaced over 5 million. Beyond the headlines, there were dozens of long-standing conflicts and smaller disasters that impacted the lives of millions of people and overwhelmed the capacity of local responders to meet the security, food and health needs of victims. The slow and sometimes inadequate response to these emergencies raise challenging questions about the capacity of the humanitarian aid system to meet the needs of people most affected by these and other disasters.

Speaking at the Dubai International Humanitarian Aid & Development Conference & Exhibition, Ross Mountain pointed out that in vulnerable countries food prices, urbanization, migration, the impact of climate change and population growth are all increasing. But as the challenges grow, the resources available in OECD countries − the traditional donors − to respond to humanitarian crises are shrinking. Nevertheless at OECD level budgetary constraints has not yet resulted in dramatic drop in humanitarian aid spending.

Given the increased scale of needs and vulnerability, a shift in attitude and working practices is needed to integrate anticipation, disaster risk reduction, preparedness and resilience into programmes. Many governments and many organizations still operate on a model that focuses on short-term crises, rather than looking at the longer term trends and their humanitarian implications. If we do not take a more participatory preventive approach, we will be responsible for countless avoidable suffering in the decades to come. Governments are increasingly linking humanitarian assistance to political, military or anti-terrorism objectives. Think Afghanistan, Yemen, Libya, Sudan, Somalia and the occupied Palestinian territory. In other cases, like Syria, governments and/or armed groups have increasingly denied access to humanitarian organizations. There has been an explosion of NGOs in recent years; but also a change in the donor landscape. The economic downturn in the West has meant a growing role for donors and organizations from the Arab and Muslim worlds, for example. This means two things. First, the international community needs to better, and “more respectfully”, engage these new players. The tendency on the part of many of us in the international community is to come thinking that money is to be given so that we, the experts, go back and do the work. The talk should be more about strategic partnerships and not about money. Forging smart and strategic partnership is one way for the international humanitarian community to better respond to today’s growing humanitarian challenges.

International humanitarian funds

International humanitarian action − aiding and protecting people in armed conflicts and disasters − has expanded dramatically in the last twenty years to become a major global field. In 2012, official humanitarian aid totalled $17.9 billion dollars and reached 73 million people. Some 75 percent of these funds came from OECD governments, Saudi Arabia and Qatar. This makes states by far the largest contributors to humanitarian aid. The remaining 25 percent came from private funds. Around $3.3bn (18.75 percent) came directly from the donations of individual citizens, and $1.1bn (6.25 percent) from private foundations. The three largest state funders are the USA, EU and UK.

According to the OECD’s report published in April 2014 total development aid (which is a more comprehensive measure than humanitarian aid) rose by 6.1 percent in real terms in 2013 to reach the highest level ever recorded, despite continued pressure on budgets in OECD countries since the global economic crisis. Donors provided a total of USD 134.8 billion in net official development assistance (ODA), marking a rebound after two years of falling volumes, as a number of governments stepped up their spending on foreign aid. An annual survey of donor spending plans by the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) indicated that aid levels could increase again in 2014 and stabilise thereafter. However, a trend of a falling share of aid going to the neediest sub-Saharan African countries looks likely to continue.

In all, 17 of the DAC’s 28 member countries increased their ODA in 2013, while 11 reported a decrease. Net ODA from DAC countries stood at 0.3 percent of gross national income (GNI.) Five countries met a longstanding UN target for an ODA/GNI ratio of 0.7 percent. The United Kingdom increased its ODA by 27.8 percent to hit the 0.7 percent target for the first time. The United Arab Emirates posted the highest ODA/GNI ratio, 1.25 percent, after providing exceptional support to Egypt. Aid to developing countries grew steadily from 1997 to a first peak in 2010. It fell in 2011 and 2012 as many governments took austerity measures and trimmed aid budgets. The rebound in aid budgets in 2013 meant that even excluding the five countries that joined the DAC in 2013 (Czech Republic, Iceland, Poland, Slovak Republic and Slovenia), 2013 DAC ODA was still at an all-time high.

The largest donors by volume were the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Japan and France. Denmark, Luxembourg, Norway and Sweden continued to exceed the 0.7 percent ODA/GNI target and the UK met it for the first time. The Netherlands fell below 0.7 percent for the first time since 1974. Net ODA rose in 17 countries, with the largest increases recorded in Iceland, Italy, Japan, Norway and the UK. It fell in 11 countries, with the biggest decreases in Canada, France and Portugal. The G7 countries provided 70 percent of total net DAC ODA in 2013, and the DAC-EU countries 52 percent. The US remained the largest donor by volume with net ODA flows of USD 31.5 billion, an increase of 1.3 percent in real terms from 2012. US ODA as a share of GNI was 0.19 percent. Most of the increase was due to humanitarian aid and support for fighting HIV/AIDS. By contrast US net bilateral aid to LDCs fell by 11.7 percent in real terms to USD 8.4 billion due in particular to reduced disbursements to Afghanistan. Net ODA disbursements to sub-Saharan Africa fell by 2.9 percent to USD 8.7 billion.

Nevertheless this survey also suggests a continuation of the worrying trend of declines in programmed aid to LDCs and low-income countries, in particular in Africa. CPA to LDCs and LICs is set to decrease by 5 percent, reflecting reduced access to grant resources on which these countries are highly dependent. Some Asian countries may see increases, however, so that by 2017 overall allocations to Asia are expected to equal those towards Africa. This will need special attention in the future

It is well-known that the European Union is the world’s leading provider of humanitarian aid. This aid, which takes the form of financing, provision of goods or services, or technical assistance, helps prepare for and deal with the crises such as natural disasters, disasters caused by human activity, or structural crises, outside the Union. The Union’s action comprises three instruments: emergency aid, food aid, and aid for refugees and displaced persons. ECHO coordinates this action and cooperates closely with partners who implement aid on the ground, in particular the United Nations and non-governmental organisations. EU Humanitarian aid policy is based on the principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence. EU Humanitarian aid must be coordinated with other policies so that it can be adapted to each situation and can contribute to long-term development goals. The EU contributes to developing collective global capacity to respond to crises. It commits to promoting reforms in the international humanitarian system, led by the United Nations, and in cooperation with other humanitarian actors and donors.

EU Humanitarian aid is financed from the ’Global Europe’ heading of the EU budget. This heading covers all external action by the EU such as development assistance or humanitarian aid with the exception of the European Development Fund (EDF) which provides aid for development cooperation with African, Caribbean and Pacific countries, as well as overseas countries and territories. As it is not funded from the EU budget but from direct contributions from EU Member States, the EDF does not fall under the MFF (the EU’s seven year framework budget).

International humanitarian funds generally are channelled through UN agencies (like the UN World Food Programme, UNICEF and UNHCR), the Red Cross and Red Crescent movement, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Humanitarian NGOs can be well known names like Oxfam, Medicines Sans Frontieres (MSF), the International Rescue Committee (IRC), CARE and Caritas, or they can increasingly be national and local NGOs that are growing fast in countries confronted by protracted conflict, chronic hunger or persistent natural disasters. Altogether, it is estimated that there are about 4,400 NGOs engaged in some form of humanitarian aid and around 274,000 humanitarian workers in the world today. The expansion of humanitarian aid and protection under UN guidance means that the international humanitarian system is becoming a nascent form of global welfare for people suffering from war, chronic food insecurity and natural disasters. Humanitarian aid is now an internationally organized safety net for many millions of people living in extreme situations as terrorized civilians, displaced people and refugees, or the victims of natural disasters like floods and earthquakes. The humanitarian system has expanded in a relatively improvised fashion, and contains hundreds of different and competing moving parts. Its many agencies may share the same strategic humanitarian goals but they each have their own organizational interests that compete for funds, profile and operational terrain.

The EU has begun to invest in these terms with its two initiatives: SHARE for the Horn of Africa worth Euro 270m in 2012/13 and AGIR for West Africa worth Euro 503m in 2012/13.21 The British Government’s Department for International Development (DFID) has also launched BRACED, a fund for NGOs to support people’s resilience to extreme climate change in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. This fund is targeting 5 million people and seeking applications from NGO-led consortia. This resilience strategy needs help if it is to inspire genuine innovations in processes, products and paradigms for building resilience. Without such innovations, these new funds, and those that follow, will be a lost opportunity in which NGOs simply bundle up old project types in new resilience wrappers.

Conclusion

Currently, the global community faces many challenges such as climate change, rapid population growth, urbanization, and water shortages. At the same time, there have global economic shifts, new actors engaged in humanitarian action, and tremendous improvements in technology. Given these challenges and opportunities, we need to improve how we respond to disasters and conflicts.

In the last ten years, the funding requirements of inter-agency appeals have increased by 600 percent from $3 billion in 2004 to $17.9 billion in 2014. However, inter-agency appeal funding received in 2013 $8.3 billion. In the same amount of time, the number of people targeted for assistance has more than doubled. The crisis in Syria is one of the worst on record given the sheer size of damage in the country and the effect on the region. The Syria Response Plan was 209 times bigger than the average appeal. More than 150 agencies and aid groups are working with local partners and national authorities to provide relief to the Syrian people in the region. In 2013, African countries like DRC, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, these countries had previously received approximately 60 percent of appeal funding, though Syria response plans received 38 percent $3.1 billion.

According to OCHA, crises are longer and more expensive. The crises in the Central African Republic, Iraq, South Sudan and Syria will remain top humanitarian priorities next year. The sharp rise in the number of people affected by conflict and of forced to flee and became dependent on humanitarian aid for their survival is expected to continue. The Global appeal for 2015 is $16.4 billion to help 57 million people in 22 countries. The UN and its humanitarian partners have launched an appeal for US$16.4 billion to help at least 57.5 million people affected by crises in 22 countries in 2015. As UN Humanitarian Chief Valerie Amos explained, “Over 80 percent of those we intend to help are in countries mired in conflict where brutality and violence have had a devastating impact on their lives…But the rising scale of need is outpacing our capacity to respond.”

As far as the EU’s preparedness is concerned one cannot be overly optimistic. In November 2013, after the European Parliament voted through the Multiannual Financial Framework which determines the European Union’s (EU) common budget and priorities over the next seven-year period, the so-called CONCORD Report was published. The 2014-2020 period is the first budgetary framework negotiated under the Lisbon Treaty, giving additional power to the European Parliament. The Parliament’s vote marks the beginning of the final stages of the process leading to the ratification of the EU budget for the seven years. The CONCORD report, ‘EU Budget 2014-2020: Fit for the Fight against Global Poverty?’ recognises that the MFF is not just a financial tool but a key tool in strengthening the EU’s place as a global development actor. The 2014-2020 period will cover both the 2015 deadline for the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals and the EU’s target to spend 0.7 percent of collective GNI on development aid, making it a crucial budget for the EU’s relations with developing countries. And yet the budget available for external action comes up short of what is needed to fulfil the many priorities and global challenges. But in 2014 the situation has dramatically deteriorated when the European Union’s humanitarian aid and development aid programmes were compromised by EU debts, and budget cuts forecast for 2015. Since 2011, the European budget has been amassing unpaid bills, which continue to rise in value. The budget by the end of 2014 was 26 billion euro in arrears, €23 billion of which are owed to the cohesion policy. This impacts the whole spectrum of European politics.

Unpaid bills in the budget category of “Global Europe”, which includes development aid and humanitarian aid, have reached 1 billion euro. The lack of funds has also forced the EU to roll back some humanitarian aid programmes. Some projects in the Sahel region of Africa, the Horn of Africa and Haiti have been postponed,” the budget Commissioner announced.

The lack of funding will also affect other humanitarian aid programmes. The impact of the EU’s current constraints on humanitarian aid is already being felt by the beneficiary countries. For example, aid to Iraqi refugees in Jordan has been reduced. NGOs are signalling that food security operations in Somalia and Ethiopia are being delayed and that their priority level is being reduced,” she added. The strain on the 2014 budget is in danger of becoming even worse in 2015, as member states have proposed significant cuts to the European Commission budget. These cuts would leave the EU unable to pay its currently outstanding bills and those that would arise in the course of the 2015 budget. The cut of 2.1 billion euros, equivalent to 1.5 percent of the total approved expenditure for 2015, will affect a broad range of European projects, but spending on development aid and humanitarian aid will probably be the hardest hit by these proposed cuts. The total budget of the section “Global Europe” could be reduced by 10 percent, representing €384 million. The budget of EuropeAid, dedicated specifically to development aid, may lose 192 million euros; 12 percent of its funding.

Globally the next two and a half years offers social entrepreneurs a real opportunity to team up with affected populations and humanitarian agencies to engage in humanitarian innovation. The new products, processes, positions and paradigms that emerge can then be presented in the UN consultation process and get traction through the Summit.

References

Bibliography and sources

AID POLICY: Humanitarianism in a changing world. http://www.irinnews.org/report/95237/aid-policy-humanitarianism-in-a-changing-world. (Accessed: 28 September 2014)

Attila Marján: Europe’s Destiny − The Old Lady and the Bull. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010. 393pp. ISBN 978-0-8018-9547-0

CONCORD report, ‘EU Budget 2014-2020: Fit for the Fight against Global Poverty?’ http://www.concordeurope.org/publications/item/283-concord-report-eu-budget-2014-2020-fit-for-the-fight-against-global-poverty

Dr Hugo Slim: Innovation in Humanitarian Action. 16pp. http://www.sbs.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Skoll_Centre/Docs/essay-slim.pdf. (Accessed: 22 November 2014)

Dubai International Humanitarian Aid & Development Conference & Exhibition, which ran from 1-3 April 2012. http://www.irinnews.org/report/95237/aid-policy-humanitarianism-in-a-changing-world. (Accessed: 28 August 2014)

Elisabeth Ferris: Too many humanitarian crises not enough global resources. http://www.globalpost.com/dispatches/globalpost-blogs/commentary/too-many-humanitarian-crises-not-enough-global-resources. (Accessed: 11 August 2014)

Euractive. http://www.euractiv.com/sections/development-policy/aid-programmes-hit-hard-european-budget-woes-309169. (Accessed: 11 January 2015)

Human Security Report Project, Human Security Report 2013: The Decline in Global Violence: Evidence, Explanation, and Contestation, (Vancouver: Human Security Press, 2013). 127pp. ISSN 1557 914X ISBN 978-0-9917111-1-6. (Accessed: 22 September 2014)

Humanitarian Crises in 2013: Assessing the Global Response http://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/support-us/events/humanitarian-crises-2013-assessing-global-response. (Accessed: 28 August 2014)

WHS 2016 Concept Note, Draft September 2013. 6pp. https://docs.unocha.org/sites/dms/Documents/WHS%20Concept%20Note.pdf. (Accessed: 22 September 2014)

World Humanitarian Data and Trends 2014 – highlights. 2pp. www.unocha.org/data-and-trends-2014. (Accessed: 22 September 2014)

http://ec.europa.eu/echo/en/news/world-humanitarian-summit-opens-online-consultation-european-region. (Accessed: 14 December 2014)

http://humanitariancoalition.ca/. (Accessed: 14 December 2014)

http://www.oecd.org/newsroom/aid-to-developing-countries-rebounds-in-2013-to-reach-an-all-time-high.htm. (Accessed: 11 January 2015)

http://www.thestar.com.my/News/Nation/2014/05/07/Jemilah-Mahmood-to-head-UN-humanitarian-summit-secretariat/. (Accessed: 22 November 2014)

http://www.unocha.org/top-stories/all-stories/2015-global-appeal-164-billion-help-57-million-people-22-countries. (Accessed: 14 December 2014)

http://www.worldhumanitariansummit.org/whs_about. (Accessed: 14 December 2014)

Original published in www.moderndiplomacy.eu

Attila Marján, Head of EU Department at the National University of Public Service, Budapest. Ilona Szuhai, Assistant Lecturer and Doctoral Student at the National University of Public Service, Budapest