By Maxwell Hormilla and Daniel Salomon

The monthly Employment Situation Report release is extremely important to investors in that it can move markets and many analysts consider it to be the best single measure of the health of the economy. To two key data points of the report are changes in nonfarm payrolls and the unemployment rate. In the days leading up to the release of the Employment Report, the market starts to brace itself by looking back at the prior month’s report and how the economic environment has changed since then. Forecasts start coming in from economists trying to predict what these key indicators will be. And the market turns to other reports, such as the ADP Employment Report and the Weekly Jobless Claims report to try and see which way the wind will be blowing. In March, we were coming off a barn-burner of a February report, which touted Nonfarm Payroll increases of 313,000 new jobs and an unemployment rate at a steady 4.1 percent. Economists anticipated some payback in March, especially considering the poor weather conditions, and we started seeing forecasts ranging from about 155,000 to 200,000 new jobs being created. Two days before the release of the Employment Situation Report, the ADP (Automatic Data Processing) Employment Report was released with 241,000 new private sector jobs in March. Across the board, the unemployment rate was anticipated to go down to 4.0 percent, supported by weekly Jobless Claims report that for the most part was steadily decreasing. And so, as of the morning of April 6th, the market was anticipating Non-Farm Payroll Increase of about 195,000 jobs and an Unemployment Rate of 4.0 percent.

Then the March Employment Situation Report came out. The results fell pretty short of expectations, as nonfarm payrolls increased by only 103,000, and the unemployment Rate stayed at 4.1 percent. Now, by all accounts this was not bad news. The economy is still expanding with new job additions and the unemployment rate suggested a tight labor market where anybody looking for a job could find one. Yet, the market reacted negatively, with major stock indices closing around 2 percent lower than they opened. The report was considered a disappointment. So, what happened? Why were the forecasts off? Why was there such a large discrepancy between the Employment Situation Report and the ADP Employment Report? We are going to take a deep dive into the data and try to explain what exactly is going on and why.

It should be noted that the Employment report is made up of two separate surveys overseen by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, or “BLS”. The First Survey is the “Establishment Survey”. It is a sampling performed directly by the BLS of more than 400,000 non-farm businesses across the United States. It is the most comprehensive labor report available, covering about one-third of all non-farm workers nationwide, and presents final statistics including the ever-important nonfarm payrolls data, hours worked, and average hourly earnings. The data sample is both wide and deep, with breakouts covering more than 500 industries and hundreds of metropolitan areas.

The second survey is the “Current Population Survey” or “Household Survey” which measures results from more than 60,000 households and produces figures representing the total number of individuals out of work, changes in size of the labor force, and the labor force participation rate. This data is compiled by the U.S. Census Bureau with the assistance of the BLS, and carries a census-like component, bringing demographic shifts into the mix, which gives the data a difference perspective.

While the Establishment Survey portion of the March Report showed a meager 103,000 increase in nonfarm payrolls, another important thing to note in this data series is the adjustment to prior months. The BLS is constantly revising its previously stated data due to receiving subsequent reports from other agencies, and further tinkering with their seasonal adjustments. February’s already good Nonfarm Payroll numbers were adjusted even higher, from 313,000 to 326,000. January, however, did not fare so well, with an adjustment down from 239,000 jobs to 176,000. On one hand, the BLS was not only reporting March numbers that fell short of expectations, but the net result of prior month adjustments was 50,000 fewer jobs created than originally reported. On the other hand, the economy still added a monthly average of over 200,000 jobs per month this year, which is not exactly bad news. And, despite less jobs being created in March, we saw a 0.3 percent increase in earnings from February, or a 12 month increase of 2.7 percent and an unchanged average hourly work week.

This raised two questions, which are in opposition to each other. The first was, if March saw only a third of February’s job additions, why was the monthly change in earnings three times that of February? Also, if this is about the 90thmonth in a row of job creation, why is the increase in earnings not more? To answer these questions, we had to dig a little deeper. When we drilled down on the month to month breakdown of job creation by industry, we noticed some key details that could explain greater increases in earnings between March and February, despite weaker job growth. We are all pretty familiar with February’s story by now, there was a lot of job creation across the board in all industries except in Information. But by far, the two big winners in February were Construction and Retail. Coincidentally (or not, as we will discuss a little later) these two industries were the big losers in March with actual decreases in the amount of jobs. This job loss definitely impacted the net payroll numbers, but what about earnings? Well, Construction and Retail jobs tend to be on the lower end of the wage scale. So an increase in construction and retail jobs in February would not have much of an impact on overall average earnings. In March, the biggest additions were in Professional Services, Education and Healthcare. These jobs tend to fall more in the mid to high range of the wage scale, so job creation in these sectors would move the needle more.

But again, 0.3 percent? That’s not exactly what most economists would expect this far into expansion with a labor market this tight. So, what is going on? Why are average earnings not increasing along with rate of job creation? It turns out we were not alone in asking this question. In February 2018, The New York Times published an article examining the very question: Why has pay lagged behind job growth? The Times proposed that we could attributed this lag to six reasons:

- Declining Unionization: Industries and regions with a large union presence tend to have higher pay levels than non-union areas. And the rate of union membership has been declining since the 1980’s. At that time, membership was in the upper teens, and today it is only about 6.5 percent.

- Restraints on Competition: Non-compete clauses have become more and more widespread across all industries. Once it only applied to highly skilled upper level employees, but now the practice has now filtered down to laborers. Typically, the biggest bumps in pay come from when these workers leave one company to go work for a competitor. These non-compete clauses severely reduce those kinds of opportunities.

- A Lagging Minimum Wage: The Federal Minimum Wage has remained at $7.25 since 2009. Obviously raising the minimum wage would boost average hourly earnings. There are arguments for and against this. The pro side of the argument is that the minimum wage really has no buying power. It did not in 2009, and it really does not today. If you increase the minimum wage, you give the lowest paid employees the ability to participate in the economy’s expansion. With this in mind, several states have passed local legislation to increase minimum wage. The Con side of the argument is simply – a rise in minimum wage is a job killer and reduces hours worked.

- Globalization and Automation: Technologies and automation have made it easier for companies to find cheap alternatives to paying their employees more money.

- Sluggish Productivity: Standard economic theory suggests that productivity and earnings should grow in tandem. From the 1970’s through 2004, productivity had grown annually at 2 percent. But starting in 2005, productivity has only grown by 1 percent.

- Outsourcing:There has been a growing trend of companies using contractors to perform certain functions that were once handled by fulltime employees. And typically, companies do not pay contractors the same rate as they do full time employees.

While the above reasons could explain why earnings have lagged behind job creation, the question remains about the sluggish March job creation numbers. The simple and most obvious answer is winter. As nice as the weather was in February, March had brutal weather for much of the country. All those outdoor construction jobs created in February became undone in March, and the bad weather disrupted transportation channels, cutting off supplies of materials reaching plants and preventing consumers from reaching stores. All analysis of the March report pointed to weather as being the single biggest factor effecting new jobs.

But this raises another question: If weather was such a factor, why did it not seem to have the same impact on the ADP Employment Report? That report presented 241,000 new jobs created, barely down from their February 246,000 jobs. Why was there such a big disconnect between these two reports? Both reports are basically presenting the same thing to the market – how many new jobs were created (or lost) in the month that just ended. However, the differences in the sources of data and how they are compiled can cause quite a divergence in the results of both reports.

As we already reviewed, the nonfarm payroll data comes from the Establishment Survey, conducted by the BLS, and is taken from 400,000 established businesses across all nonfarm industry sectors, including government. The ADP report is the joint effort of Moody’s Analytics and ADP and is made up of data pulled from ADP’s client base, which makes up roughly one-fifth of the private sector in the United States.

The ADP data is coming from a much narrower slice of the pie, and the data is more scrubbed than that collected by the BLS – each month’s data is entered into a time series that goes back decades, extreme values are removed, matching pairs are created, seasonal adjustments are made, and then the data is further adjusted to match the size and scope of the BLS report. This difference in compilation alone explains why the two reports often differ. However, there is another key difference in both reports – this one in the nature of the data itself.

The Nonfarm payroll data released by the BLS only includes employees who have actually been paid for a job. The ADP report includes any worker on the company’s books, regardless of their status or if they are actually owed payment. This means that temporary employees or hourly laborers that were not used, and therefore not paid in a given month, would not show up on the BLS’s Establishment Survey, but would show up in ADP’s data feed. This key difference could explain why, in a month where bad weather continuously interrupted business as usual, ADP would report more new jobs than the Employment Situation Report did. Taking an average of the difference between the BLS nonfarm payroll numbers and the number put forth by the ADP querying of their user data, we get an average of 89,000,000 for the last 10 years and an average of 78,000 over the last 5 years.

The second survey that makes up the Jobs Report is the Household Survey. This survey draws data from 60,000 households across a range of geographic regions and demographics. The survey looks to count all who have a job and those who are unemployed and actively looking for work. The unemployment rate is then calculated by the number of unemployed people actively looking for work divided by the labor force. Therefore, the key takeaway from this survey is the unemployment rate, the change in the labor force, and the labor force participation rate.

In March, the unemployment stayed locked in at 4.1 percent for the sixth month in a row. This is a very low unemployment rate and a good indicator that we are in a very tight labor market, or a labor market where there are more jobs than there are people looking for work. However, the number actually fell short of expectations, as many economists were forecasting unemployment to reach 4.0 percent in March, and as low as 3.8 percent by the end of the year. The labor force decreased by about 158,000 people in March, while the labor force participation rate also fell by 0.1 percent to 62.8 percent.

The Household Survey is actually a part of a much more comprehensive survey called the CurrentPopulation Survey (or CPS). The Unemployment Rate is just one metric taken from this survey. There are also narrower and broader metrics taken. The unemployment rate, also called U3, is the percent of unemployed people as a percent of the labor force. That remained unchanged in March at 4.1 percent. Note the following:

- U1 – is made up of those who have been unemployed for 15 weeks or longer as a percent of the labor force. This is the chronically unemployed population, and in periods of economic expansion it usually only captures structural unemployment. March U1 seasonally adjusted rate remained unchanged at 1.4 percent

- U2 – is made up of job “losers” or people who involuntarily lost their jobs or completed a temporary job and now find themselves back to being unemployed. This is where we usually find our Cyclical Unemployment. March saw a decrease in this rate from 2 percent to 1.9 percent

- U4 – is our first of the broader measures. This rate includes discouraged workers and counts them along with unemployed people who are actively looking for work. March decreased from 4.4 percent to 4.3 percent

- U5 – This measure augments U4 by including marginally attached workers. Marginally attached workers include anybody who could potentially work but who is not, and would not, fall under the category of discouraged. March U5’s results saw a drop from 5.1 percent to 4.9 percent

- U6 – The broadest unemployment measure, U6 includes all part-time employees in the unemployment calculation. The March U6 results saw a drop from 8.2 percent to 8.0 percent.

Thus, when we drill down to a narrower view, our cyclical unemployment metric, U2, is going down while our structural unemployment remains constant. All of our broader unemployment rates are also going down, so we can attribute the lack of decrease of our U3 metric to the decrease in the labor force and the labor force participation rate.

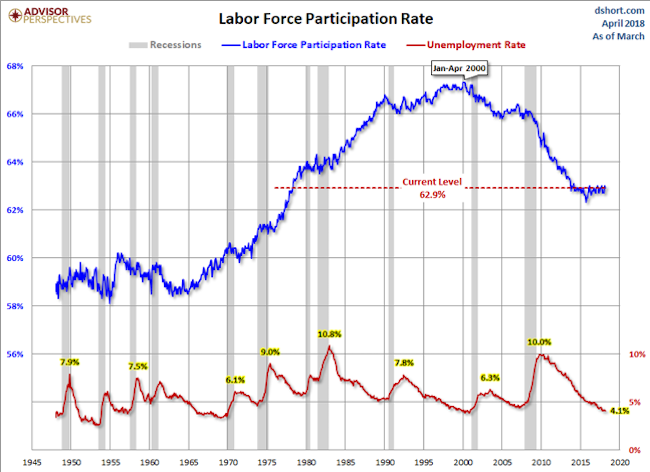

The above graph from Advisor Perspectives shows a nearly 60-year history of the U3 Unemployment Rate to Labor Force Participation Rate. From this graph you can see that we are historically at the lower end of the unemployment rate scale. This is not really news to anybody. What is interesting though is how the labor force participation rate is not moving in the direction you would expect. We are currently at a 62.9 percent labor participation rate which is on par with the rate we were at in the late 1970’s when we were at a much higher unemployment rate. This is a concern. You can see from the graph that our trouble began at the start of the Great Recession, when the unemployment rate shot up to 10 percent. The labor participation rate declined at a steady rate through the recession and well into recovery. Participation stabilized somewhat in the last few years, and we’ll take a closer look at that in a moment. But the key takeaway from this graph, we believe, is the effect of the baby boomer population. The surge in participation began in the early 1970’s, just as the first wave of boomers entered the labor force. When the Great Recession hit, that first wave of baby boomers was just about to reach retirement age. Between now and about 2030, the baby boomer retirement rate will be a downward moving force on the ratio of unemployment to participation rate.

So, what does this all mean going forward? In the short term for the non-farm payroll prediction for the month of April and for GDP in the long-term future? For the short term we have made a prediction using the following considerations: previous NFP, current jobless numbers, current employment indicators, consumer confidence, and any influences that current politics and policies may have. The previous Nonfarm payroll is taken as neutral. Even though the nonfarm payroll came in under predictions, the actual number for the month was still positive, at 103,000. Also, when considering the harsh weather for the month and February’s amazing performance, it tends to even out. Some data to reflect upon:

- Jobless Numbers, we looked at Initial Jobless claims as well as continuing jobless claims only. Other reports such as the Challenger job cuts were not available. Initial jobless claims are neutral at the moment with non-seasonally adjusted down by 30,000, while seasonally adjusted is up by 9,000. Continuing jobless claims are up early in April but have merely returned to the value seen at the same week last month.

- ISM non-Manufacturing and Manufacturing PMI were both up at 58.8 (up 2.2 percent) and 59.3 (up 2 percent) respectively. JOLTS Job Openings, showed a small down turn to 6.05 Million. Over all very good preliminary numbers for the month.

- Consumer Confidence was represented by the University of Michigan Consumer Confidence Index, which shows a value of 97.8 percent, which is down 3.6 percent from last month. Politics are summed up by more of the same uncertainty in the Tariffs and the effects of the tax-cuts.

What does this all mean? The interpretation is that we are plateauing. We may have seen the bottom and are at full unemployment or at least very near it. Coupled with neutral overall numbers in the above, the prematurely predicted nonfarm payroll change numbers for April (to be released on May 4, 2018) is expected at 140,000 with a 4.1 percent unemployment rate.

For the longer-term, the following factors should be considered:

- Strengthening Global Demand: Global GDP expected to increase by 4 percent up from last year’s 3.75 percent. China’s pace of growth is expected to be exceeded by India soon, China may be approaching economic maturity. The middleclass is growing which will be increasing domestic demand and China should begin to see a shift from production export base to more imports relying on the US and its Intellectual Property.

- Oil glut nears an end, so cheap oil is on its way out. And with new technologies in horizontal drilling that make the US competitive even in current oil prices, energy exports should be going up for the US.

- Tax reform could either leave companies with more money to improve GDP at the end of the year or leave more money for firms to buy back stock… only time will tell. This is one of those things that will help and hurt along the way.

- Natural disasters/weather… while losses where suffered in some areas due to the hurricanes, the rebuilding of these areas will only be a temporary moment of positive production… the rough year in weather will hurt in the long run.

- The shifting workforce demographics: As baby-boomers go away, the expected job growth added each month is expected to decline to 125,000 on average down from the roughly 200,000 we have been experiencing. So as a result, if GDP growth were to stay where it’s at, we may see gains in productivity that have not been realized for some time now. However, there is uncertainty in what this will do to wage inflation/inflation and as the cost of workers goes up, how much outsourcing will occur in the near future as a result… This is a wild card.

The general prediction: Expect slow and steady growth over the next 2 years with some hiccups here and there as items such as the tax policy solidifies, and whether or not the pending tariffs ever actually materialize or what their true intent is.

(We thank Professor Parul Jain at Rutgers Business School for her insights and support for our work)

Maxwell Hormilla and Daniel Salomon are MBA candidates at Rutgers Business School