Dousing the sovereignty wildfire

In time, the current spat between French President Emmanuel Macron and his Brazilian counterpart Jair Bolsonaro regarding the Amazon rainforest may become a mere footnote. But other rows between collective and national interests are sure to erupt, and the world needs to find a way to manage them.

By Jean Pisani-Ferry

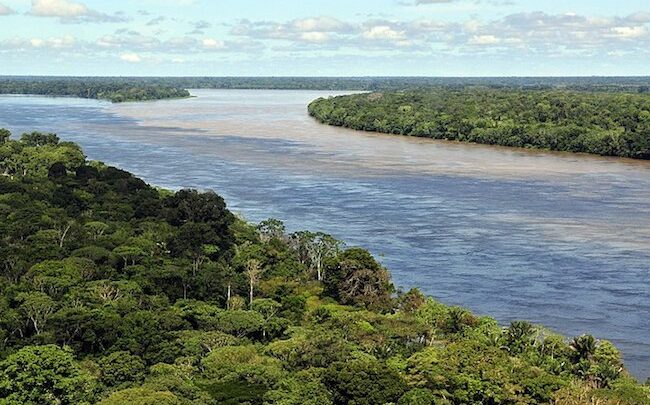

On the eve of the recent G7 summit in Biarritz, French President Emmanuel Macron described the Amazon rainforest as “the lungs of our planet.” And because the rainforest’s preservation matters for the whole world, Macron added, Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro cannot be allowed “to destroy everything.” In reply, Bolsonaro accused Macron of instrumentalizing “an internal Brazilian issue,” and said that for the G7 to discuss the matter without the countries of the Amazon region present was evidence of a “misplaced colonialist mindset.”

The row has since escalated further, with Macron now threatening to block the recently concluded trade deal between the European Union and Mercosur, unless Brazil – the largest member of the Latin American trade bloc – does more to protect the forest.

The Macron-Bolsonaro dispute highlights the tension between two big recent trends: the increasing need for global collective action and the growing demand for national sovereignty. Further clashes between these two forces are inevitable, and whether or not they can be reconciled will determine the fate of our world.

Global commons are nothing new. International cooperation to fight contagious diseases and protect public health dates back to the early nineteenth century. But global collective action did not gain worldwide prominence until the turn of the millennium. The concept of “global public goods,” popularized by World Bank economists, was then applied to a broad range of issues, from climate preservation and biodiversity to financial stability and internet security.

In the post-Cold War context, internationalists believed that global solutions could be agreed upon and implemented to tackle global challenges. Binding global agreements, or international law, would be implemented and enforced with the help of strong international institutions. The future, it seemed, belonged to global governance.

This proved to be an illusion. The institutional architecture of globalization failed to develop as advocates of global governance had hoped. Although the World Trade Organization was established in 1995, no other significant global body has seen the light since then (and the WTO itself does not have much power beyond arbitrating disputes). Plans for global institutions to oversee investment, competition, or the environment were shelved. And even before US President Donald Trump started questioning multilateralism, regional arrangements started restructuring international trade and global financial safety nets.

Instead of the advent of global governance, the world is witnessing the rise of economic nationalism. As Monica de Bolle and Jeromin Zettelmeyer of the Peterson Institute found out in a systematic analysis of the platforms of 55 major political parties from G20 countries, emphasis on national sovereignty and rejection of multilateralism are widespread. When John Bolton, the current US national security adviser, wrote in 2000 that global governance was a threat to “Americanism”, many regarded the idea as a joke. But few are laughing now.

True, nationalism hasn’t won the war. Despite Brexit and the rise of far-right parties in Italy and other countries, the European Parliament election in May did not produce the feared populist landslide. Growing segments of public opinion simply want policymakers to address problems in the most effective way, including at European or global level if needed.

Nowadays, however, international collective action cannot be based on further universal treaty-based obligations. The question, then, is which alternative mechanisms can address global challenges effectively while minimizing encroachments on national sovereignty.

Some models are already at work internationally. On trade, for example, burgeoning “variable-geometry” groupings are tackling new issues related to “behind-the-border” regulations such as technical standards, and the blurring of the distinction between goods and services. Corporate giants’ global abuse of market power is being confronted by the extraterritorial rulings of national competition authorities. Likewise, the effective strengthening of bank capital ratios resulted not from any international law, but from the voluntary adoption of common, non-binding standards. And although the world is lagging on climate-change mitigation, the 2015 Paris climate agreement has prompted several countries to act, including by mobilizing regional and city governments, and triggering private investment in clean technologies.

But because not all global problems are alike, such mechanisms will provide a suitable template for collective action only in certain cases. When the various players are willing to act, a modicum of transparency and trust-building is sufficient to ensure cooperation. In other cases, however, the temptation to free-ride or abstain can be countered only by powerful incentives or even sanctions.

That brings us back to the Amazon fires. The interests of Brazil and the international community are not aligned. For Brazil’s small farmers and big agri-food corporations, the economic value of the land matters considerably. But the rest of the world is mainly concerned with the rainforest’s ecological and biodiversity value. Time horizons also differ: unsurprisingly, the wealthy in the global North value the future more than the poor in the South do. Even if large segments of Brazilian society value the preservation of the rainforest, it is wishful thinking to believe that moral suasion and nudges alone will resolve differences between Brazil and its external partners.

In the case of the Amazon, the only hard instruments available are money and sanctions. Through transferring more than $1bn to the Amazon Fund since 2008, Norway already subsidises the preservation of the environmental service that the rainforest provides to the world (it interrupted transfers in August in protest against Bolsonaro’s policies). Macron’s alternative is to coerce Brazil into valuing the environment by making trade deals and other international agreements conditional upon the country managing its natural resources in a sustainable way.

Both options are problematic. Payments open an enormous Pandora’s box and reaching a significant scale requires an agreement on who will actually bear the burden: the annual social value of carbon capture by the Amazon rainforest is hundreds of time bigger than the Norwegian transfers. Coercion also is tricky, because there is only an oblique logical relationship between deforestation and trade. But because there are no other options, solutions will probably have to involve some combination of the two.

In time, the Macron-Bolsonaro spat may become a mere footnote. But other rows pitting global concerns against national sovereignty are sure to erupt, and the world needs to find the way to manage them.

Jean Pisani-Ferry holds the Tommaso Padoa Schioppa chair of the European University Institute in Florence and is a Senior Fellow at Bruegel, the European think tank. He is also a professor of economics with Sciences Po (Paris) and the Hertie School of Governance (Berlin).