British troops massacred Indians in Amritsar – and a century later, there’s been no official apology

By Sumit Ganguly, Indiana University

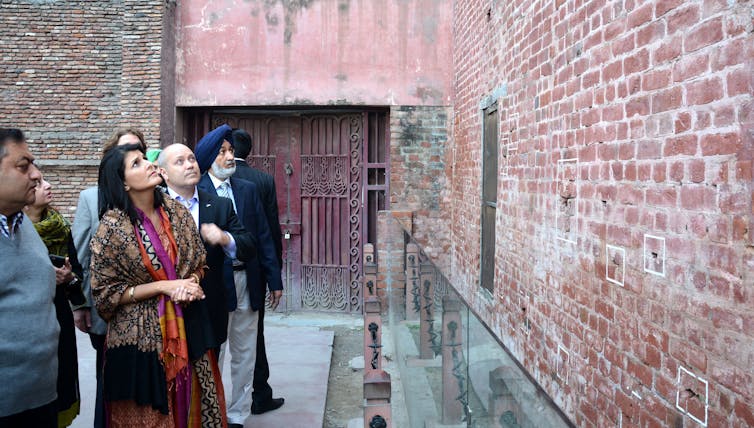

The Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby recently visited the site of a brutal massacre that happened in 1919 under the British colonial rule in India and offered his personal apologies. He expressed his “deep sense of grief” for a “terrible atrocity.”

Earlier in April, then U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May told the House of Commons that the episode was “a shameful scar on British-Indian history.” However, she had stopped short of apologizing.

The massacre is still remembered in India as a symbol of colonial cruelty. Here’s what happened a hundred years ago.

Killing unarmed protesters

After World War I, the British, who controlled a vast empire in India, agreed to give Indians limited self-government due to India’s substantial contribution to the war effort.

These reforms, named the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms after the secretary of state for India and the viceroy of India, promised to lead to more substantial self-government over time.

However, around the same time the British had passed the draconian Rowlatt Acts, which allowed certain political cases to be tried without trial. And the trial was also to be conducted without juries. The acts were designed to ruthlessly suppress all forms of political dissent.

The Rowlatt Acts were designed to replace the constraints on political activity that had been embodied in colonial rules, known as the Defense of India Rules, which had been in force during World War I.

Not surprisingly, there were widespread public protests, led by the noted Indian nationalist leader, Mahatma Gandhi.

As part of this nationwide agitation, some 10,000 individuals gathered in a park in the northern Indian city of Amritsar on April 13, 1919. Since this protest was in defiance of a curfew which prohibited political gatherings, Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer, who was stationed in the nearby city of Jalandhar, decided to take action.

Troops under his command blocked the sole entrance to the park, called Jallianwallah Bagh. Without warning they opened fire. The British officially estimated that 379 people died. The unofficial count was more. Close to 1,200 were injured.

Dyer’s men stopped firing only after they had run out of ammunition. The soldiers did not offer any medical assistance to the wounded, and others could not come to their aid because of the imposition of a curfew on the city.

An apology long overdue

Then viceroy of India, Lord Chelmsford, convened an inquiry commission which led to Dyer being relieved of his command. However, upon returning to the United Kingdom, he found support for his actions among a segment of the British population.

In India, there was widespread shock and horror over this wanton use of force. The Nobel Laureate in literature, Rabindranath Tagore, protested by renouncing his knighthood, which he had received from the British Crown in 1915. Writing to the viceroy, Tagore decried “the disproportionate severity of the punishment inflicted upon the unfortunate people.”

As a political scientist who has written on the impact of British colonialism on India, I believe that the legacy of this episode, along with a host of other ugly events, continues to trouble Indo-British relations.

Britain, for the most part, has failed to come to terms with its tragic colonial heritage in South Asia and elsewhere. In the wake of the the archbishop’s apology, I believe, it is time for the British government to follow suit.

An unequivocal apology to the memory of the victims is long overdue.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter. ]Sumit Ganguly, Distinguished Professor of Political Science and the Tagore Chair in Indian Cultures and Civilizations, Indiana University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.