Ultralong bonds: Can they work?

The Treasury Department is entertaining the idea of issuing ultralong-term debt instruments with a possible maturity of 100 years. The real gamble is whether investors will buy such an instrument and what are the risks they would face in owning these bonds.

The Treasury Department under President Trump is seriously considering issuing bonds with maturities of 50 to 100 years as a way to keep the federal government operating. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin has been studying the various ins and outs of issuing such bonds, known as ultralong Treasuries, and whether there is a market for these instruments. The real concern is how they could affect the national debt, the interest expense the Federal government would be facing, and how receptive investors would be.

Current national debt situation

The key reason that the Trump Administration is deeply interested in issuing ultralong Treasury instruments is the increase of the National Debt. As of November 1st, 2019, the National Debt exceeded $23 trillion marking the first time in U.S. history that it reached this milestone. Of this $23 trillion in debt by the federal government, $17 trillion is held by the general public such as private American citizens, pension funds, commercial banks, mutual funds, insurance companies, and foreign countries such as China, Japan, and South Korea. The remaining $6 trillion is held by loans within the federal government such as Social Security.

This is an amazing situation financially because when Donald Trump took office in January 2017, the National Debt was at $19.9 trillion. The National Debt has grown 16 percent since the Trump Administration took over. But the growth of the National Debt has been greatly helped by the growth of the Federal Budget deficit under the Trump Administration. For the 2019 budget year, the Federal Budget deficit reached $984.4 billion which is the highest level since 2012. In order to support the budget deficit, the Federal Government must borrow huge sums of money, thus increasing the nation’s debt.

The Trump Administration has held the nation’s debt ceiling hostage at times by shutting down the Federal Government, but this only puts off the inevitable as far as the increase in the National Debt. The Federal Budget deficit went up 26 percent from 2018’s shortfall of $779 billion. In order to pay for the increasing Federal Budget deficit, the Federal Government must continue to borrow at astronomical amounts, not seen since the height of World War II. And since Treasury debt instruments carry the safety and security of repayment at literally no risk, the Federal Government can continue to borrow huge sums of money without any hinderances. But the problem is trying the entice investors to purchase more U.S. debt even as the National Debt reaches new levels.

Use of ultralong debt

Ultralong debt can best be defined as debt that has a maturity of 50 to 100 years. Ultralong debt can work for the borrower as a way to entice lenders to invest in a very long-term debt instrument that can be handed down from one generation to another. Currently, the longest-term debt instrument that the U.S. government issues is 30-year Treasury bonds which are regarded as very conservative due to the perceived safety by investors of principal and interest. The Federal Government has never defaulted on any of its debt and does not recall or make early payments on its loans.

If the Federal Government issues a 30-year Treasury bond, investors know they will receive thirty years of interest payments and then get back the principal that was originally lent. Investors also like that Treasury instruments are highly marketable in that there are always buyers of U.S. government debt. The Treasury instrument with the highest degree of liquidity are Treasury bills, commonly known as T-bills. There is a large market for T-bills and investors know they can turn them into cash in a relatively short time. The only real drawback of Treasury instruments is the low interest rate. Ultralong debt issued by the Federal Government would probably fall into this same category, enjoying many of the same benefits as Treasury bonds. The Federal Government has previously issued 50-year bonds in 1911.

The Treasury Department has expressed interest in issuing ultralong bonds starting in 2017 despite concerns by the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee (TBAC) which represents large bond-trading firms. The TBAC stated its uncertainty of demand by institutional investors such as pensions or commercial banks and the relatively high issuance costs for these bonds. But the Treasury is attempting to finance the National Debt with very low interest rates and lock in these rates for 50 to 100 years. The Treasury Department would not need to conduct new auctions on new debt issues and therefore not roll over the debt for a long time.

There are other key reasons for issuing ultralong debt:

New financing of the National Debt: As stated earlier, ultralong debt could be used to finance the National Debt using low interest rates for a very long time. At the pace that the National Debt is growing, the ability to finance it will end up costing the Federal Government hundreds of billions of dollars. So, the Treasury Department must come up with a new plan to not only sustain the National Debt, but support the Federal Budget deficit that is nearing $1 trillion, and entice investors to purchase Treasury instruments.

Useful for Pensions: Ultralong debt could be very useful for pensions as pensioners are living longer. Pensions need to invest in assets that will last many years and have a high degree of certainty in their cash flow or in this case, the interest generated by ultralong Treasury bonds. Pensions are finding that pensioners are living longer than anticipated and more money must be paid to them than planned. In order to match pension plan assets with pension plan liabilities, ultralong bonds could be that instrument that solves the problem.

Insurance company annuities: Ultralong bonds could also be an enticing investment for insurance companies in order to finance annuities, especially fixed. Fixed annuities are generally backed by corporate and government long-term bonds, mortgages, and longer maturity notes. Insurance companies would find ultralong Treasury bonds useful for the guaranteed interest payments and safety of principal at maturity. The only problem for insurance companies would be the low interest rates on ultralong Treasury instruments.

Private investors: Private investors could use ultralong long bonds as a method to pass their wealth from one generation to the next. Private investors would be able to have the peace of mind of reliable cash flow for years to come and the safety of the principal being passed on to future generations. The demand would not just be by investors in the United States but globally.

Purchase by Social Security: Ultralong bonds could be a useful asset by the Social Security program in the United States as a method to maintain payments to recipients. As recipients are getting older, living longer, and increasing in number, the Social Security program could use ultralong bonds to successfully finance payment of benefits. Social Security would probably be a large purchaser of ultralong bonds since recipients such as the Baby Boomer Generation will be collecting benefits in mass in the coming decades and a reliable, sustainable cash flow is vitally necessary to keep the program viable. It will not be unusual for the average age of Social Security recipients to be well into their 80’s and that more live to be over 100 years old.

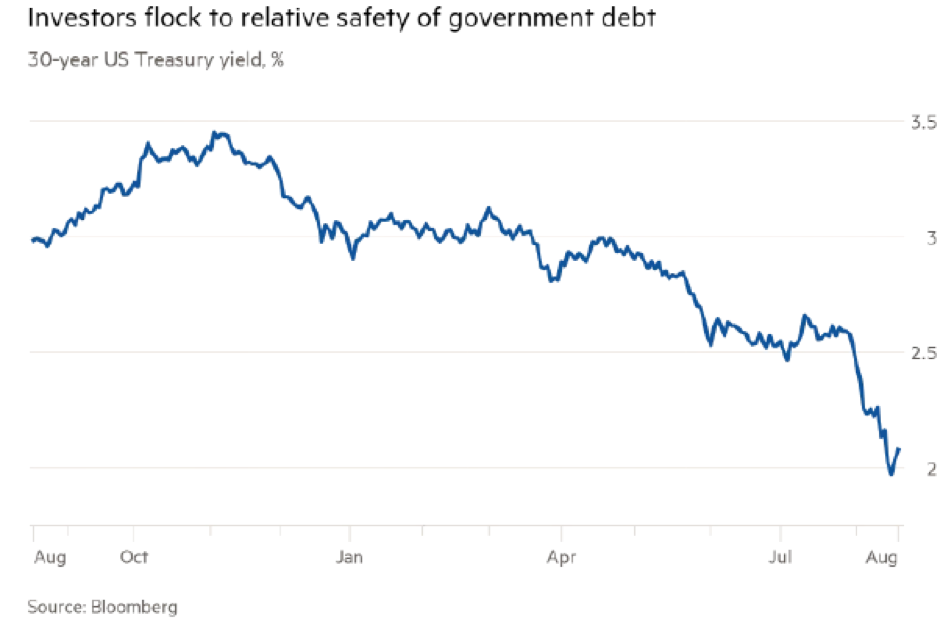

Counterbalance to negative interest rates: A concern among lenders and investors is the toll that negative interest rates will have on the total return of many portfolios. If the Federal Reserve Bank decides to use negative interest rates to stimulate the American economy in case of a recession, then lenders and investors may seek the safety and security of ultralong bonds even though the return may be low. The Federal Reserve has expressed the possibility of using negative interest rates to stimulate the American economy in the event of an economic slowdown and that they are limited in the number of tools in its financial toolbox. The global marketplace is currently using negative-yielding debt instruments totaling $16.4 trillion and growing. Therefore, lenders and investors will probably flock to ultralong bonds as a safe haven investment where even low interest rates are better than negative rates.

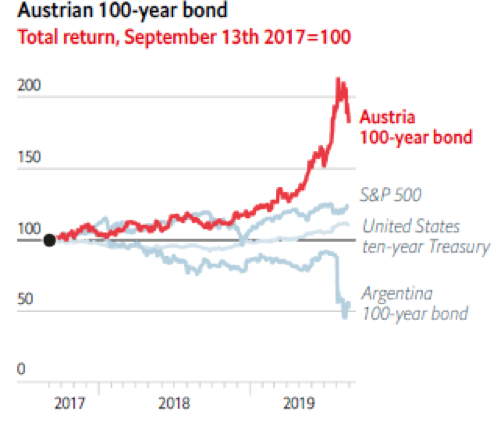

Currently in use: Ultralong bonds are currently being used by corporations and governments. In 2016, Norfolk Southernissued bonds maturing in 2105 while in the same year Goldman Sachs sold a 50-year bond issue. The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), a federally owned government body has a bond maturing in 2060. In August 2019, the University of Pennsylvania issued a bond maturing in 2119 with a 3.61 percent yield while 30-year Treasury bonds were only at 2.5 percent. Among the nations issuing ultralong bonds are Austria, Japan, Mexico ($1 billion with a 100-year bond offering denominated in dollars, pounds, and euros), Canada, Belgium, Ireland (€100 million 100-year bonds), Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. As interest rates continue to go down, more nations are tempted to issue ultralong bonds at cheaper rates and save money in the long and short term.

Will investors buy ultralong bonds?

The real question is whether investors and lenders will purchase ultralong bonds? These bonds may look tempting now that interest rates are low and the yield on ultralong bonds are comparatively higher. But the problem is that investors and lenders are taking a big risk in purchasing ultralong bonds if interest rates go up. If market rates climb due to the Federal Reserve Bank and other central banks raising interest rates because inflation starts rearing its ugly head, then the value of ultralong bonds will decline. Also, investors and lenders will probably have a difficult time trying to sell their ultralong bonds on the open market due to decreased marketability and less demand. There is also the possibility of increased default risk in the future for some of these bonds. Investors and lenders will have sunk billions of dollars, euros or yens into these instruments and have bonds worth a few cents each in case of default. Ultralong bonds are like any other bonds that have their returns and risks. The key question is: How much risk can an investor or lender tolerate?