People are a valuable resource that every nation needs. Whether as consumers or workers, humans are a vital resource in order to help any nation grow and develop economically. By acting as consumers, people pump money into an economy by spending in order to purchase goods and services from companies that in turn employ workers. These workers earn a salary for their labors and for the contributions they make to a company in order for it to invent better processes, techniques, and products. But unless there are people, none of this is possible.

Currently, there is what demographers call a “global fertility crisis”. This means there are less babies being born who will eventually become consumers and workers. But most importantly, they will replace the individuals who will die, either prematurely or due to old age, and this will result in a population decline in many nations. Countries such as Italy, Japan, Spain, China, Australia, and the United States are experiencing declining numbers in their respective populations that will have long-term economic, financial, and policy implications. Unless something is done to reverse this global trend, the situation will only get worse.

What is happening

Many nations are experiencing a serious decline in their fertility rates. Foremost among these nations is Japan in which, according to the United Nations, saw their fertility rate decline from 2.75 children born per woman in the 1950s to 1.44 in 2020. This means a population decline of one million people since 2015. Other nations, such as Spain and Thailand, will experience serious reductions in their population of greater than 50 percent from the years 2017 to 2100. Spain is expected to see its population decline from 46 million to below 23 million in this time period, while Thailand will go from 71 million to below 35 million in the same span.

Going around the world, the decline only gets worse. For example, Central and Eastern Europe, along with Central Asiawill see their population head downward from a peak of 418 million in 2023 to a low of 324 million. If the economies of the nations located in these regions are expected to grow, then a severe population decline will not help. Countries such as Bulgaria contained 9 million at the conclusion of the Cold War but saw its population shrink to 7.1 million by 2017. For Bulgaria, the situation is only expected to worsen since some estimates feel that its population will decline further to approximately 5.4 million in 2050. In the same time period, nations such as Poland and Ukraine are expected to lose another 6 million in population while Hungary will shed 1.5 million people.

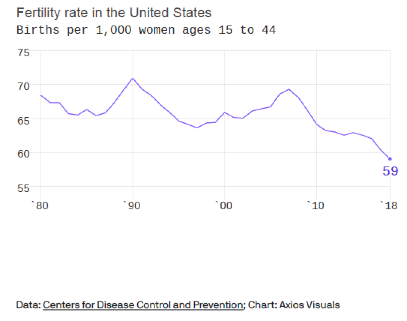

The United States is not immune to the global fertility crisis. Long seen as a nation that has a growing and robust population, the United States is starting to witness a decline in its growth. The year 2007 saw the fertility rate peak at 2.1 children born per woman. However, by 2016, the nation’s fertility rate dropped to 1.8. The United States has long been known as a nation that has permitted a fairly large amount of immigration from other countries to be used as a way to make up for any declines in population growth. Immigrants would bring along their families and start new ones in their adopted country. However, this is no longer true as the fertility rates in the United States have seen a decline since 1990 in all the major racial and ethnic groups who have relocated. For example, the fertility rate among Latinas has dropped precipitously from 3.0 children per woman in 1990 to 2.4 children per woman in 2010 and for black women the rate has gone from 2.5 to 2.0. There are analysts who feel that the onslaught of Covid-19 will only make matters worse since people will be fearful of having children in a pandemic that may last two or three more years.

Why it is happening

There are numerous reasons why the global fertility crisis is occurring.

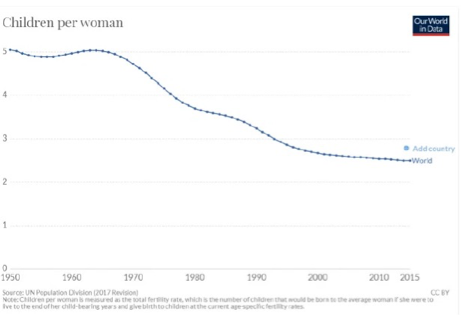

First, the decline in the global fertility rate is occurring due to drop in the total fertility rate, or the TFR. The TFR represents the rate in which a population is able to replace itself from one generation to the next making up the replacement fertility rate. Demographers state that a minimum of two children are needed to make sure that there is a steady rate of population from one generation to the next. The TFR has seen a global decrease of five live births for every women in the 1960’s to a level of 2.43 births in 2017 which demographers feel is close to the critical threshold.

There is also the preferred context for having children. Now more women want to have children after completing their education, attain economic and financial security, and become involved in a stable relationship. But there are very often problems in achieving these goals and many women either have fewer children or none at all. Many women delay having children until they feel they are ready, but some forgoe having children since they feel they are never ready.

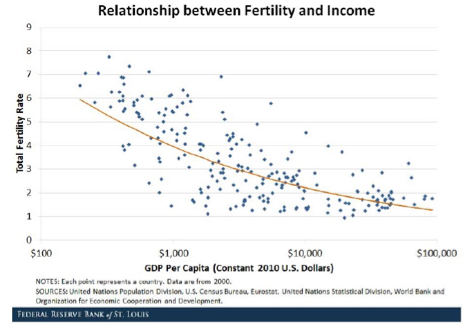

Another reason fewer babies are being born is the cost. Many parents will readily tell anyone that having children costs money. This includes feeding, clothing, education, child care, and health care expenses. With the cost of living, as well as the costs involved in raising a child, many people put off having children or decide to have one or two at the most. If the parents are wealthy, then the chances of having more children can increase substantially. There have been studies showing that there is a correlation between financial and economic wealth and increases in births.

There is also the increase in the use of contraceptives and better quality of contraceptive technology. More reliable, cheaper, and increased access to modern contraception makes it easier for a women or a couple to put off having children. There have been economists who have attributed approximately 40 percent of the fertility decline that started after 1957 to improvement in contraceptive access.

Increased college attendance, especially among women, could be another reason for women either delaying or having fewer children. More women have attended college or graduate school than in the past. This means putting off having children in order to complete their education. Also, with more students taking on student loans, it may mean putting off having children in order to pay off those loans.

Another key reason for the decline in the TFR is the trend by young people to postpone bearing children. In 1970, there were approximately 168 births for every 1,000 women in the 20 to 24 age brackets, while there were 73 births for every 1,000 women in the 30 to 34 age brackets. Now the trend is changing. For the first time in American history, in 2009 the birthing rate for women in the 30 to 34 age brackets, which is 97.5 births for every 1,000 women, exceeded that of women in the 20 to 24 age brackets at 96 births for every 1,000 women. The birthing rate for teen age girls, ages 15 to 19, has declined to 34 births for every 1,000 girls, which is the lowest ever in American history.

Economic implications

There are various economic implications of the global fertility crisis. The first involves replacing workers who have retired or left the labor force. There will always be a number of workers who will either take early retirement, retire at their appropriate age, or die prematurely. This is regarded as normal and totally expected. However, if there is an insufficient number of people to take the retiree’s places, then there is a severe worker shortage that will only get worse as time goes by. Without children being born at the normal rate, and then eventually entering the workforce in later years, there will be a worker shortage. What is occurring now is that the U.S. labor force is not growing at the rate it should and has slowed down precipitously from an average of 2.5 percent per year in the 1970’s to approximately 0.5 percent annually between the years 2010 to 2016. This rate is expected to be constant at this level for the next ten years. The problem is made worse if immigration into the United States is tightened considerably by the federal government and that companies are having a very difficult time finding new workers for industries such as construction, healthcare, and farming.

Another economic problem with a global fertility crisis is that societies will begin to age at a faster pace. If the number of senior citizens continues to increase and there are no babies to replace them in society, it will mean that the average age of many countries will go up. For a nation to see its economy grow, it needs young people who will consume a variety of products and use multiple services. Older people are past the consumption stage and will only purchase products and goods they need to survive. They are not looking to use new technology or take vacations and spend money. Senior citizens will often travel but at a slower pace. Younger people want to explore new places, use the latest technology, and try exotic foods. This means that younger people will be highly inclined to spend more and often. It is projected that by the end of the 21st century, 2.4 billion people will be over age 65, yet those under age 20 years old will only be at 1.7 billion. This imbalance between old and young people is not good for the global macroeconomy.

For those nations that provide vast and complex social programs, the global fertility crisis will hurt them especially hard. For example, Europe will be severely impacted by a shortage of children which will mean an eventual shortage of workers in the labor force. Many countries in Europe rely on higher tax revenues in order to pay for healthcare programs, pensions for the elderly, and a wide social safety net for all members of European society. The only way to pay for these programs is higher taxes or more workers in the labor force to pay taxes to support these programs. But when does the increasing amount of taxes become too much for workers to bear? These social programs rely on money coming in and money going out. If there is not enough money coming in, then policymakers will find themselves in a bind trying to provide the ageing population the services they will desperately need. European Union governments have tried to address their fertility crisis problem. For example, in 2018 Italy announced September 22nd as “Fertility Day” in order to encourage its citizenry to do its civic duty and reproduce in order to bolster the nation’s declining population.

A key economic implication is that many nations will start to experience declining Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the coming decades. There will be an eventual domino effect if the fertility crisis deepens. If there are fewer people, then fewer goods, products, and services will be consumed. This will lead to lower production or economic output in the long run, and eventually slower economic growth which translates into lower global GDP. This will ultimately mean that living standards will eventually decline also. This concept was brought forth by Stanford University economics Professor Charles Jones in his paper, “The End of Economic Growth?” Professor Jones sets forth a model of what could occur with global population decline. Professor Jones states that as overall output declines, global living standards would experience stagnation as the population disappears on a gradual basis. The domino effect is that there will be significant reduction in research and development, consumption, production, and even the introduction of new services. The global macroeconomy will slow down and the world will experience a vicious cycle as low fertility occurring in one generation will lead to low fertility in the following generation, and so on.

What will the future hold?

While this seems like a very scary future, it can be changed. But this means a revaluation of public policy in order to encourage more babies being born and that the TFR actually increasing over time. For example, government, at both the local, state, and national level will need to formulate policy that will provide support systems to working mothers and families who want to have children. This would mean programs such as subsidized day care and nursery school for children from infants to preschool. Child care is very expensive and subsidized child care would take a huge burden off the backs of working mothers and families who have a difficult time making ends meet. There must also be laws and regulations, on state and national levels, that would create family-friendly workplaces. Programs such as extended maternity leave, with full pay, could help working mothers care for their infants longer and create more loyalty to their employing companies.

There should also laws and regulations that allow paternity leave with full pay, so that new fathers could share in the care and feeding of their newly born children. There should also be new tax policies designed to benefit secondary earners instead of penalizing them for having children or taking an extended leave of absence to raise their babies. The bottom line is that unless new polices are introduced to encourage women to have babies and families to have more children, the economic implications will mean a downturn that will be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to avoid.