By Dmitry Velmeshev, University of California, San Francisco

Autism affects at least 2% of children in the United States – an estimated 1 in 59. This is challenging for both the patients and their parents or caregivers. What’s worse is that today there is no medical treatment for autism. That is in large part because we still don’t fully understand how autism develops and alters normal brain function.

One of the main reasons it is hard to decipher the processes that cause the disease is that it is highly variable. So how do we understand how autism changes the brain?

Using a new technology called single-nucleus RNA sequencing, we analyzed the chemistry inside specific brain cells from both healthy people and those with autism and identified dramatic differences that may cause this disease. These autism-specific differences could provide valuable new targets for drug development.

I am a neuroscientist in the lab of Arnold Kreigstein, a researcher of human brain development at the University of California, San Francisco. Since I was a teenager, I have been fascinated by the human brain and computers and the similarities between the two. The computer works by directing a flow of information through interconnected electronic elements called transistors. Wiring together many of these small elements creates a complex machine capable of functions from processing a credit card payment to autopiloting a rocket ship. Though it is an oversimplification, the human brain is, in many respects, like a computer. It has connected cells called neurons that process and direct information flow – a process called synaptic transmission in which one neuron sends a signal to another.

When I started doing science professionally, I realized that many diseases of the human brain are due to specific types of neurons malfunctioning, just like a transistor on a circuit board can malfunction either because it was not manufactured properly or due to wear and tear.

RNA messages in the cell drive function

Every cell in any living organism is made of the same types of biological molecules. Molecules called proteins create cellular structures, catalyze chemical reactions and perform other functions within the cell.

Two related types of molecules – DNA and RNA – are made of sequences of just four basic elements and used by the cell to store information. DNA is used for hereditary long-term information storage; RNA is a short-lived message that signals how active a gene is and how much of a particular protein the cell needs to make. By counting the number of RNA molecules carrying the same message, researchers can get insights into the processes happening inside the cell.

When it comes to the brain, scientists can measure RNA inside individual cells, identify the type of brain cell and and analyze the processes taking place inside it – for instance, synaptic transmission. By comparing RNA analyses of brain cells from healthy people not diagnosed with any brain disease with those done in patients with autism, researchers like myself can figure out which processes are different and in which cells.

Until recently, however, simultaneously measuring all RNA molecules in a single cell was not possible. Researchers could perform these analyses only from a piece of brain tissue containing millions of different cells. This was complicated further because it was possible to collect these tissue samples only from patients who have already died.

New tech pinpoints neurons affected in autism

However, recent advances in technology allowed our team to measure RNA that is contained within the nucleus of a single brain cell. The nucleus of a cell contains the genome, as well as newly synthesized RNA molecules. This structure remains intact ever after the death of a cell and thus can be isolated from dead (also called postmortem) brain tissue.

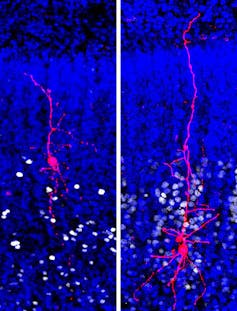

By analyzing single cellular nuclei from this postmortem brain of people with and without autism, we profiled the RNA within 100,000 single brain cells of many such individuals.

Comparing RNA in specific types of brain cells between the individuals with and without autism, we found that some specific cell types are more altered than others in the disease.

In particular, we found that certain neurons called upper-layer cortical neurons that exchange information between different regions of the cerebral cortex have an abnormal number of RNA-encoding proteins located at the synapse – the points of contacts between neurons where signals are transmitted from one nerve cell to another. These changes were detected in regions of the cortex vital for higher-order cognitive functions, such as social interactions.

This suggests that synapses in these upper-layer neurons are malfunctioning, leading to changes in brain functions. In our study, we showed that upper-layer neurons had very different quantities of certain RNA compared to the same cells in healthy people. That was especially true in autism patients who suffered from the most severe symptoms, like not being able to speak.

Glial cells are also affected in autism

In addition to neurons that are directly responsible for synaptic communication, we also saw changes in the RNA of other non-neuronal cells – called glia. Glia play important roles in regulating the behavior of neurons, including how they send and receive messages via the synapse. These may also play an important role in causing autism.

So what do these findings mean for future medical treatment of autism?

From these results, I and my colleagues understand that the same parts of the synaptic machinery which are critical for sending signals and transmitting information in the upper-layer neurons might be broken in many autism patients, leading to abnormal brain function.

If we can repair these parts, or fine-tune neuronal function to a near-normal state, it might offer dramatic relief of symptoms for the patients. Studies are underway to deliver drugs and gene therapy to specific cell types in the brain, and many scientists including myself believe such approaches will be indispensable for future treatments of autism.![]()

Dmitry Velmeshev, Postdoctoral Scholar, University of California, San Francisco

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.