The Ukraine crisis – the other side

By Raphael Lapin

“I cannot forecast to you the action of Russia. It is a riddle, wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma; but perhaps there is a key. The key is Russian national interest.” Although these words were uttered by Sir Winston Churchill in October 1939, they might as well have been voiced today.

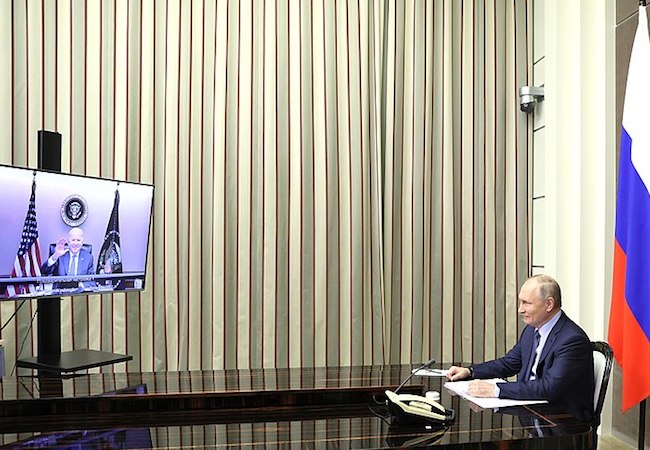

The talks between Russia and the United States about the Ukraine crisis this week so far has resulted in a stalemate. The good news is that both sides have agreed to continued dialogue. The final outcome can either be the catalyst for East-West relations to improve which will advance global security, or East-West relations to further deteriorate, which could potentially strengthen the entente between Russia and China. For President Biden, if managed with wisdom and skilled diplomacy, it is not too late for an opportunity to salvage his presidency from diminished ratings, and redeem him from what many believe to be the Afghanistan fiasco.

U.S. politicians, media, and news outlets are marching to a war cry. They are demanding that Russia unconditionally withdraws all troops from the Ukrainian border and are threatening an unmitigatedly tighter sanction regime should Russia choose not to comply. Again, U.S. hubris, media sensationalism, a collective national mind-set still stuck in the Cold War, and an out-for-blood, sports-minded public hoping for a “team victory”, is driving foreign policy, rather than skilled diplomacy, sound judgement and effective negotiation.

As long as we insist on seeing this crisis entirely and exclusively from a U.S. perspective, we don’t stand even a negligible chance of resolution. As Sir Winston Churchill said, the key to unlock this enigma are Russian national interests. To negotiate effectively, it is imperative that we make every effort to uncover, acknowledge and deeply understand those interests.

In this essay, I examine how Russia perceives the Ukrainian tensions. This broader perspective will allow us to be better equipped and qualified to jointly design solutions that will meet their concerns while at the same time meeting U.S. interests.

Towards this end, it is useful to begin by surveying the two primary frameworks of international relations to contextualize the historic relationship between the East and the West: Realism (or sometimes referred to as Realpolitik), and Liberalism.

Simply put, the realist framework is based on, and a reaction to the belief that countries, as individuals, are immutably selfish, egotistical, power-hungry, competitive and cannot be trusted. As such, the path to national security is to exert power, dominance and hegemony to achieve self-interests at all costs, even at the expense of the destruction of other nations if necessary. It is the international equivalent of “each man for himself” and “The Law of the Jungle”. Niccolo Machiavelli, the 15th century Italian diplomat, is arguably the father of realism, which was propounded in more recent times by Hans Morgenthau, a world-renowned 20th century international relations academic.

The danger of a foreign policy based on the realism framework is what is known in international relations theory as the security dilemma. Due to lack of trust, cooperation and communication, any state’s action is interpreted by other states based on perception and suspicion. For example if one state benignly increases troops along a border to monitor human or drug trafficking, the neighboring state might interpret this as an intention to attack and will respond by sending an even greater number of troops to her own borders. The first state will see this as a threat and increase mobilization even further as the vicious cycle continues and the danger of war looms.

It was a foreign policy based on realism and the resulting security dilemma that caused the almost catastrophic event during the Cold War. The USSR interpreted the deployment of U.S. Jupiter ballistic missiles in Turkey and Italy as an intent to attack and responded by sending their own missiles to Cuba. The U.S. in turn saw the Cuban-based missiles as a threat to its own national security and sovereignty which it was ready to protect at all costs, even if it meant sinking Soviet ships en route to Cuba. This was the closest that the Cold War came to a full-scale nuclear war and illustrates the flaws of a foreign policy based on realism.

As then, it is also a foreign policy based on outdated realism that has contributed to the current tensions over Ukraine.

The liberalist view of international relations, on the other hand, is that global security is better achieved through engagement, transnationalism, economic interdependence and cooperation that serve mutual interests. Liberalists believe that nations will effectively collaborate and partner through authentic and genuine discourse, relationship-building, trust and negotiation. This liberalist view of international relations is rooted in the thinking of the 17th century English philosopher, John Locke and the 18th century German philosopher, Immanuel Kant. A paradigm of international relations driven by liberalist thinking in recent times is the European Union model.

The current Ukraine crisis notwithstanding, a stated foreign policy item on the early Biden agenda was to restore alliances and build coalitions that would help to contain China. A key alliance without which we cannot counter China is with Russia,. This will require in any event, a swing of the international relations pendulum from the Trump realpolitik back to a more liberalist approach, at least with Moscow, with whom unfortunately our relations have deteriorated over the last two decades.

The first step towards improving U.S. – Russian relations in general and to resolve the Ukraine crisis in particular, is to acutely understand the genesis of the deterioration, and by association the Russian national interests, and to address the problem at its core.

The current strained relationship between the United States and Russia can be subtly epitomized by the somewhat comical meeting between Secretary of State Clinton and Foreign Secretary Sergei Lavrov in March 2009. At this meeting, Clinton, with theatrical flair, presented Lavrov with a large, colorful, symbolic pushbutton with an inscription in Russian which was intended to say “reset” (perezagruzka). This was to convey to the Russians that the U.S. was ready to reset the button on U.S.-Russian relations. Unfortunately, due to the similar etymology, the inscribed word was incorrectly translated and the Russian word for “exploit” or “overcharge” (peregruzka) was used instead. Although Lavrov laughed politely, this blunder underscored how Russia perceived the manner in which they were being treated by the U.S.

This perception goes back to the dismantling of the Soviet Union in 1991. Russia believed that she had reached a deliberate, informed and independent decision to voluntarily restructure the Soviet Union due to political, economic and geopolitical self-interests. Any involvement of the U.S to help facilitate this, Russia understood to be through mutual consent and accord, and not due to any U.S. influence, coercion or pressure. President Reagan understood how important this perception was to Russia when he told his aides at the first meeting with Gorbachev in Geneva in November 1985: “Let there be no talk of winners and losers. Even if we think we won, to say so would set us back in view of their inherent inferiority complex”. (Reagan & Gorbachev: How the Cold War Ended. Jack Matlock. pp 152-153).

Despite Reagan’s directive of which President George H.W. Bush was surely aware, he nevertheless later brazenly violated it when in January 1992, he declared: “By the grace of God, we won the cold war”. This conveyed that the U.S. saw themselves as the victor and the Russians as the vanquished. Russia found this insulting and saw it as a belligerent assault on their sensibilities of national pride, sovereignty, history, dignity and identity. Russia’s determination to counter that U.S. perception significantly contributed to Russian foreign policy ever since, and many of their geopolitical moves can be reasonably interpreted through that lens. In fact as late as September 2013, in a speech at the Valdai Discussion Club, Putin stressed Russia’s desire for “independence and sovereignty in spiritual, ideological and foreign policy spheres”. He added that “the time when ready-made lifestyle models could be installed in foreign states like computer programs, has passed!” – An obvious reference to what he perceived to be American imperialism imposed by the victor. This was precisely the setback that Reagan referred to and feared in Geneva.

Russia’s sensitivity to being treated as the defeated was exacerbated by NATO’s expansion progressively in an easterly arc into the Eastern Bloc countries of The Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland in 1999. This further demonstrated a U.S. expression of dominance and an assertion of supremacy. This perception was reinforced when NATO launched a bombing campaign against Yugoslavia the same year, despite Russian opposition and without authorization of the U.N Security Council – a flagrant condemnation of Russian eminence.

This brings us back to the current Ukraine crisis. Should Ukraine achieve full NATO membership status, this would complete the easterly arc of NATO expansion to the very doorstep of Russia, a doorstep that shares a long frontier with Russia. Looking at this in the context of the earlier NATO expansion into the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland, it is not hard to see how Russia might interpret this as a carefully planned strategy and a dire threat to its national security and sovereignty.

In addition to this, Russia also sees NATO’s easterly expansion as a brazen violation of a promise made by James Baker to Mikhail Gorbachev. On February 9th, 1990, Baker warranted that NATO would move “not one inch eastward” – a commitment made in consideration of Gorbachev agreeing to German reunification. (Incidentally, when Putin questioned this, he was told that the promise was made to the Soviet Union which no longer exists and not to Russia). Violated promises erode trust.

Alexis de Tocqueville, the 19th century French diplomat wrote: “The greatness of America lies not in being more enlightened than any other nation, but rather in her ability to repair her faults”. To improve U.S-Russian relations and to unlock the enigma, we should not only try to resolve the narrow Ukraine issue but also respond to broader Russian national interests. We need to repair the relationship faults and fissures at their very source. The U.S should magnanimously allow Russia to feel as a partner, not as the vanquished; as an equal, not as the defeated, while at the same time vigorously defending American interests. This means inviting Russia to negotiate and co-design a Pact of Partnership or a Charter of Cooperation that will identify areas of common interests and policies, while addressing differing ones; where and how we might collaborate or compete; how we will manage conflict regions of the world in ways that can meet our convergent and divergent interests; on which issues will we consult with each other and on which issues will we merely inform one another; and what operational protocols and channels of sustained communication will we establish.

With regard to Ukraine, this might be an impetus to re-examine NATO’s role and mission, which was originally designed to counter the Soviet threat during the Cold War, an organization which Russia no doubt sees as discriminatory and prejudiced today. Perhaps it is time to swivel NATO to the China threat and think about including Russia. It is only with a strong U.S. – Russia alliance that we can then engage China and invite them to choose between being welcomed as a genuine partner in building global stability and security, or to confront the formidable force of the U.S. – Russia alliance within a unified NATO.

These negotiations will take patience, persistence and perseverance, but engaging in the process itself with the necessary dialogue and exchange, will already contribute to a deeper understanding of each other’s needs, concerns and interests – a foundation for mutual respect, trust, cooperation and ultimately improved global security. This might indeed be the key to transform Russia from a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma into a rational, collaborative and cooperative partner.

Raphael Lapin is an international conflict scholar, professor of law, and a dispute resolution specialist. He is principal of Lapin Negotiation Services, a Los Angeles-based negotiation and dispute resolution consultancy and has been published in the Crisis Group’s Ethiopian Insight and Egypt’s English Weekly on the dispute between Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt around the Grand Renaissance Dam and in the Jerusalem Post about the Palestinian-Israeli conflict; He has appeared on Al Jazeera TV with regards to his expertise on international conflict.