By Damien Dean

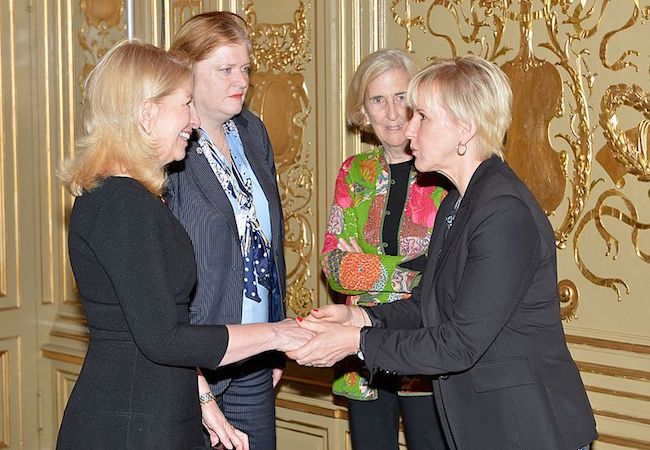

After the term “feminist foreign policy” was popularized in 2014 by Margot Wallström, the foreign minister of Sweden, who announced her country’s foreign policy mantra as feminist, foreign policy “experts” were quick to denounce it, saying feminizing foreign policy does not bring about any substantial change on the ground, and it is very naïve and emotional to think that feminist foreign policy is applicable to the global issues.

Gender perspective on global politics surely raises questions as to whether it is a “realistic enough” vision for international affairs and “determinative enough” to alter the way the actors interact with one another. Many ponder the feasibility of this approach in a world where the international society is perceived with the terms homo homini lupus and “life is nasty, brutish and short,” to use the words of Thomas Hobbes, a revered medieval political theorist.

Though Sweden’s principles still do operate within the conceptual framework of the orthodox theories like Realism and Liberalism, we shall admit the fact that a sovereign nation declared its foreign policy as feminist is a critical yardstick to demonstrate how far the feminist theorizing of international relations has penetrated into a field where male dominance is prevalent.

Let’s be clear on what feminist foreign policy is not: feminist foreign policy does not or should not only advocate greater participation of women (rather it is the first and probably the most essential step towards change) in positions of power because it is aware of the difference between gender and sex. While acceding the fact that having more head of states simply would not change the world, feminist foreign policy is expected to change the state interaction by over-turning gender relations.

We said feminist foreign policy is aware of sex and gender. While sex refers to the biological categories of maleness and femaleness, gender refers to the totality of the symbolic meanings that reinforces the gender categories such as masculinity and femininity. Hence, contrary to what many half-informed pundits think on feminism, feminist foreign policy does not suppose that the reign of women will be more peaceful because women are more caring, emotional, and empathetic. Thinking thus in fact would render feminist foreign policy dysfunctional.

Therefore, make no mistake: feminist foreign policy promises to make the world more blissful not because women are peace-lover, docile creatures but because looking at the global affairs through gendered lenses gives a whole new array of opportunities for us to contemplate on and take action for. Take for example warfare: when looked through the gendered lenses, warfare is seen as a privileged male activity, an activity in which women’s presence is only a supplement to that of men, often in the role of prostitute, rape victim etc…

The Promised Future

Feminist foreign policy merits attention, not for its provocative title, but for its aptitude to blend ideals with practicality. The world is laden with problems which are global in scale and local in effect. Not as panacea, but as a remedy, the feminist foreign policy can help alleviate the global problems stemming from the stalemate of the international system by offering insightful solutions.

It is proven that when women are meaningfully engaged in peace-processes, the likelihood of success increases. Because the experiences of man and woman are different during a conflict, i.e. women are one of the most vulnerable and severely affected groups during a conflict, women’s contribution to conflict-resolution tend to be more impactful and long-lasting. Though this is the case, the warring parties and their patrons in Syria, for example, have excluded women from the peace negotiations to date, unable to understand the neglect of women’s voices might be one of factors that fails the negotiations.

Similarly, a 2008 RAND Corporation report revealed that the women participation in nation building process stimulates both political stability and economic prosperity. Examining the nation building efforts in Afghanistan, the report found out that the inclusion of women in the Afghan political process by securing and enshrining their political and economic rights in the constitution in the early stages of reconstruction activities affected the stability of the country positively. Drawing conclusions from this study, countries involved in nation building efforts in different parts of the world should design policies that will create stronger institutions whose success depends upon the integration of the gender perspective.

Presumably, the most immediate effect of such foreign policy will be on disproportionate population growth, one of the biggest obstacles in front of sustainable economic growth, which in many ways reinforces unequal relations between countries. Economic development based on population growth makes nothing more than adding artificial numbers to the economic figures and makes no good whatsoever for improving the well-being and prosperity of people. Sustained economies with the inclusion of women in the economy whose reproductive rights are secured properly will make the world economy more stable hence the world politics by curbing the population growth in the developing world.

Yes, all the references above call for a greater participation of women. But we all shall keep in mind that feminist foreign policy starts advocating women’s presence in all aspects of politics. This is a stepping stone for more fundamental changes. It is time to think more creative and clever approaches to global politics for doing the same thing again and again and expecting different results is defined as madness.