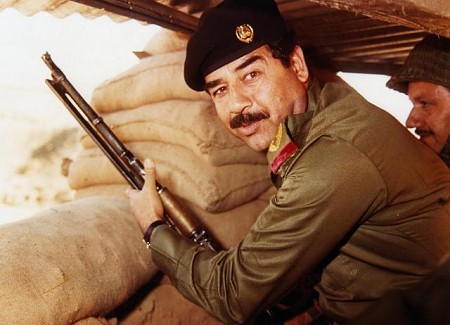

Reassessing Saddam Hussein’s legacy in Jordan

By Omer Faruk Topal

Saddam Hussein, the former president of Iraq who ruled with an iron fist for 24 years, is still a matter of debate in the Arab world. Despite his execution and the extensive de-Baathification program in Iraq, which aims to remove all Baath elements from the state institutions and the society, some Sunni groups in the country which have been marginalized under Nouri al-Maliki’s Shiite-led government have turned back to Saddam Hussein’s legacy. These groups carry Baath-era Iraqi flags in protests, they celebrate Saddam’s birthday, and elegize his execution. Even though Shiites and Kurds, the main victims of Saddam’s ruthless rule, are not happy with the rise of his ghost from the grave, this trend is not limited to Iraq.

In Jordan, a small country located in the middle of the regional crisis, it is interesting to observe that some hotels still continue to fly the Baath-era Iraqi flag. Even on souvenirs, such as cups or small carpets, the Baath era’s three-star flag inscribed with Allahu Akbar (God is Great) is used. One can see Saddam Hussein’s pictures in shops, in buses, or on the rear windows of cars. Recent developments in Iraq and Syria further strengthen this commemorative sentiment.

There are a number of reasons for people to yearn for Saddam Hussein. The first reason is his antagonism toward Israel. Rancorously opposing Israel wins credit for politicians in almost every Muslim country. However, in order to analyze Jordan, one should keep in mind that more than half of the Jordanian population is comprised of Palestinians. There were approximately 200,000 inhabitants in the region that composes the modern-day Jordanian state when Britain first drew the borders. Amman was a small town at that period. Every expansion of Israel produced influxes of Palestinians to Jordan and now, these Palestinians constitute a huge segment of Jordanian society. Even though many of them integrated into Jordanian society, the idea of “free Palestine” is still the dream of many. For instance, a school teacher whom I met in Amman told me that he named three of his daughters after Palestinian cities in order to make them always remember their origins. Saddam’s anti-Zionist rhetoric, the aid he offered to Palestinian groups, and the missiles he sent to Israel (almost everybody I talked to attached special importance to this) make Saddam Hussein the defender of Palestine in the eyes of many.

Iranian involvement in the Middle East, particularly in Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Yemen is considered by many Arabs as a Persian conspiracy against Arab unity. It is from this point that the second reason of Saddam’s popularity can be deduced. For many Arabs, especially nationalist ones, Iraq is the gate of the Arab world and a barrier to Iranian influence. If Iraq falls, the whole Arab world will fall under Iranian influence. Therefore, Saddam is considered as a defender of the Arab world due to his struggle against Iran, which is highly appreciated by the people. The rise of pro-Iranian militia groups in the region and the annihilation of national unity in Lebanon and Yemen are attributed to the fall of the Saddam regime. Iran’s military, economic, cultural, and diplomatic presence in the Arab Middle East is not only considered as a geopolitical threat, but also an assault to Sunni Arab identity. In brief, Arabs are not happy to see the commander of Quds Force as the “governor of Baghdad” and consider this as a humiliation to all Arabs.

The Syrian civil war and current crisis in Iraq crystallize Sunni and Shiite identities in the Middle East. In this vicious sectarian conflict, both Sunnis and Shiites feel themselves as victims under pressure. Under these circumstances, Saddam Hussein is remembered as the defender of Sunni identity. His merciless policies against Shiites are not supported, but the defenders of Saddam have been claiming that Iraq cannot be ruled without strict policies due to the country’s lack of a democratic political tradition, obstacles in establishing a Western-type sovereign state, and an unrealized understanding of nationhood. His supporters throughout the Arab world have legitimized his rule with the current situation. They claim that under Saddam’s rule, Iraq was a tyranny with security. Then, car explosions, suicide bombers, and looting were strange to Iraqis. Now, Iraq is a tyranny with insecurity. There is no improvement to democracy, rule of law, or liberties. Furthermore, growing insecurity divides the country.

Last but not least, Saddam’s stance against the West, especially against the U.S., increases his postmortem popularity. The reasons behind anti-Westernism in the region are beyond the scope of this article, but the existence thereof is an undeniable reality. The public in the Middle East can easily be blinkered by anti-Westernism, disregarding that the outcome of this attitude may harm the region or the people themselves. The same is true regarding the idolization of Saddam Hussein.

Growing violence in the region radicalizes people. Their discourses, political and religious leaders, and historical figures become more radical. In this atmosphere, a community’s pain assumes ultimate importance, overriding everything else, and leaves no room for reconciliatory and pluralist thinking. When I asked a taxi driver in Salt, 30 km west of Amman, after his laudatory speech for Saddam Hussein whether the man was not a dictator, he responded quickly, “He was the best dictator I had ever seen.”