It’s time to stop accusing Kuwait of funding terror

By Robert Vessels

Panicked attempts by Washington to cut off the head of extremism in Iraq and Syria are likely causing the recession of some of the Gulf’s most progressive policies.

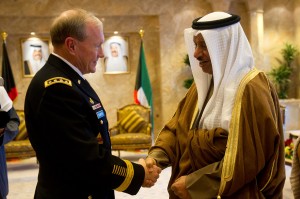

In September, the chair of the Joint Chiefs of staff, General Martin Dempsey, estimated that the U.S. would need to train up to 15,000 moderate Syrian opposition forces in order to effectively confront Islamic State’s (IS) military capabilities. The train and equip program’s current goal is to prepare 5,400 fighters annually. While the U.S. will be waiting nearly three years to reach its desired troop count, IS has already welcomed 15,000 fighters from around the world thanks to its successful recruitment plan.

The United States Senate approved a $1.1 trillion spending bill on Saturday that allots up to $500 million in support of vetted elements of the Syrian opposition. The bill includes a two year authorization for training appropriately vetted rebels in Syria with the hope that the moderate opposition can begin to successfully combat IS and al-Qaeda affiliated Jabhat al-Nusra (JAN).

Although the Senate gave the green light for funding appropriately vetted rebel groups, it’s not likely that the funding will start immediately if the vetting process is thorough. Meanwhile, IS is grossing up to $430 million a year or more from oil, extortion, private donations, and even organ trafficking; which has set it apart from its predecessor al-Qaeda. Granted, IS has to use a significant portion of these funds to provide social services across its vast territory. Syria’s moderate opposition, however, is playing a serious game of catch-up, and it has the U.S. Department of Treasury playing the blame game. David Cohen, the Treasury’s undersecretary for terrorism and financial intelligence, has recently scrutinized Kuwait and Qatar in public forum for not cracking down on private charities funneling money into Syria.

According to Elizabeth Dickenson’s December 2013 report for The Brookings Institution, a think tank funded by Doha, private donors in Kuwait have raised hundreds of millions of dollars, which are funneled into Syria with little to no accountability. However, Newsweek recently reported that IS has only received up to $40 million in the last two years from private charities in the Gulf. Most private charities responsible for funding Syrian rebels are organized by Kuwait’s Salafi clerics who see the conflict through a sectarian lens as a religious obligation.

Until recently, donors have taken advantage of Kuwait’s political atmosphere, which offered loose economic policies and freedom of assembly. In response, Kuwait passed legislation last year that outlawed the funding of terror groups and established the Financial Intelligence Unit within its finance ministry to investigate money laundering and other illicit behavior. This has not been enough to prevent the ire of Cohen, who labeled both Kuwait and Qatar as “permissive jurisdictions for terrorist financing.” Cohen has also praised Saudi Arabia and the UAE for their efforts in stymieing private donations to IS. By using Saudi Arabia as a role model to pressure Kuwait into cracking down on charities that fund IS and JAN, the U.S. risks dismantling the most progressive government in the Gulf.

According to the New York Times, Kuwait has taken advantage of the pressures and the global focus on IS to silence political opposition. In a move that resembles Kuwait’s more conservative neighbor Saudi Arabia, the government is increasingly revoking citizenships of those critical of the state. This can be seen as a tactful response to U.S. pressures to crack down on the private funding of terrorism since the Salafi clerics that run the charities are often the most dissident. An immediate crackdown on all donors, however, is risky because the political unrest that followed the Arab Spring still hasn’t completely settled and Salafi clerics have influence over Kuwait’s rural communities to rally more protests.

Washington has been critical of Kuwait and Qatar’s shortcomings, but the U.S. has not blacklisted the financial institutions within IS territory—Washington’s go-to weapon for stifling the economic means of extremist groups. Already largely unpopular among the communities residing in IS control, Washington clearly does not want to shut down the local economy and increase resentment. However, if the Treasury is unwilling to do everything within its power to sever IS’ cash flow, perhaps Cohen should refrain from questioning the Kuwaiti government’s willingness to combat terror. The U.S.’ most progressive ally in the Gulf recently criminalized terrorist funding, but, like the U.S., Kuwait does not want to stir unrest among its public with an abrupt economic crackdown.

Robert Paul Vessels is a researcher at the University of California, Berkeley.