By Yağmur Erşan

Increasing tensions between Russia and the EU led Russia to prioritize developing its relations with Asian countries. Russia has recently increased its dialogue with Japan, South Korea, India, Indonesia, Pakistan and China, and has signed various agreements in different sectors. Among these Asian countries, extending relations with China is one of the most vital goals because China is the biggest trade partner of Russia, with $88bn in trade volume in 2014 and hopes of an increase to $100bn in 2015. Moreover, the Russian economy largely depends on the export of energy resources, and China is most likely to be Russia’s biggest consumer for future gas deliveries due to China’s increasing energy consumption. Also, China is the only country in the region that can provide financial support to the Russian economy, which has recently been experiencing recession due to western sanctions. Although Russia favors selling gas to Europe, there are economic and political limitations that Putin discussed at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum: “We have to admit that energy consumption in Europe is moving slowly due to low economic growth rates, while political and regulatory risks are increasing.” To further explain Russia’s desire to expand relations with China, Putin said “given these circumstances, our desire to open up new markets is natural and understandable.”

Energy agreements will link two giants

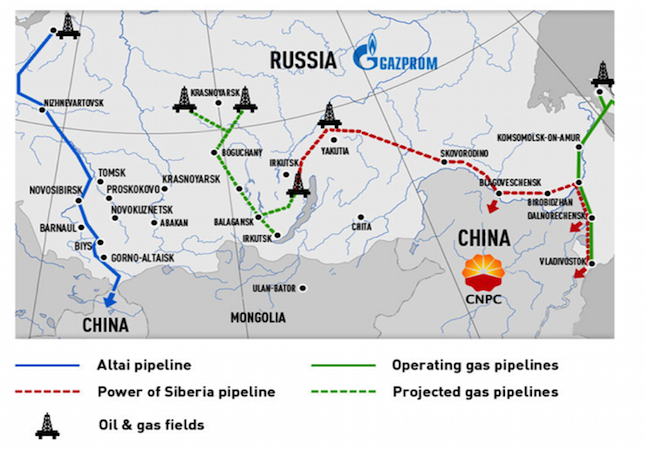

As a result of this economic rapprochement, Russia and China signed two mega energy agreements in last year that will help Russia to diversify its export destinations. The first was a $400bn mega deal, the biggest single trade agreement in history, which was signed between the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), China’s largest energy company, and Russian energy giant Gazprom in May, 2014. According to the agreement, Russia will provide 38 bcm of gas to China for 30 years starting in 2018. The deal includes the construction of a pipeline called “Power of Siberia” that will transfer gas from eastern Siberia to northern China, Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei metropolitan area, and the Yangtze River Delta in the east. This new infrastructure will also make gas available for Russia’s Pacific ports. Thus, Russia could provide gas not only to China but also to Japan, South Korean and other Asian markets.

The economic burden is expected to be $70bn for the pipeline, related transportation and storage infrastructure. CNPC will provide $22bn to ensure that the shipment of gas will begin in 2018. Although negotiations for gas trade between Russia and China started almost a decade ago, they could not be finalized mainly because of the price mismatch. Russia insisted that China buy gas at the European prices while China insisted on the lower prices. Although there is no certain statement about the price, looking at the cost of the deal and the amount of gas deliveries, analysts estimate that it is between $335-350 per thousand cubic meters. China was patient throughout negotiations regarding the price because its conditions are different than the EU. Although EU’s energy consumption consists of almost 25 percent natural gas, China’s dependence on natural gas is only about 6 percent of its total energy consumption. Coal is the major resource in China’s energy complex, making up 70 percent of China’s consumption, so China does not need to rush the deal. The Ukraine crisis provided great advantages to China and, due to the deterioration of the Russian economy by U.S. and EU sanctions, Russia consented to the prices that China wanted.

According to the second agreement that was signed in November, Russia will provide an additional 30 bcm of gas to China over 30 years from western Siberia by way of the Altai pipeline, negotiations for which began in 2006 but halted in 2013 due to the priority given to the “Power of Siberia.” This second agreement was discussed more than the first one because many experts, such as Mike Bird from Business Insider, interpreted it as a political move by Russia to give a message that Russia is not bound to the west. If this second deal were realized, it would be quite significant for China; Gordon Kwan from the Nomura Holding in Hong Kong claims that the two deals could meet nearly 17 percent of China’s natural gas needs by 2020, which is a crucial amount.

Possible challenges awaiting the Altai pipeline project

After the signing of this deal, Gazprom chairman Alexey Miller said, “The overall volume of gas exported to China might exceed supplies to Europe in the medium term.” “However, the idea that Russia’s exports to China may surpass its exports to Europe is quite unlikely because of the many challenges surrounding the fate of the agreement.”

First of all, this agreement is merely a memorandum of understanding, so it is not legally binding, and the price, which was very problematic for the realization of the “Power of Siberia,” has not yet been negotiated. Moreover, the gas prices in Asia are indexed to the oil prices, which have declined by more than half since June, strengthening China’s hand in the negotiations. The US and Canada are building LNG terminals to export gas to the Asian market, which will decrease the LNG prices in the Asian market. China’s import of gas from Russia via the pipeline will increase the supply of gas in the region, which will also affect the fall of the LNG prices. As a result, China will likely be more assertive in obtaining a price reduction. Secondly, China finds the western route unfavorable because this pipeline would enter China from the northwest, in the Xinjiang province. Nevertheless, this area is rich in energy reserves, with around 425 bcm in total energy reserves in the region. Thus, it is able to produce around 23 bcm annually. Further, Central Asia has already been suppliying gas to that region, which is far from the center of the population. Thirdly, local governments are still in favor of using coal, due to its low cost and rich reserves, instead of natural gas. Another big controversy is whether or not Russia can afford the Altai pipeline in these economic conditions when it is expected to spend $55bn for the “Power of Siberia.” Even if Russia can produce the money for this pipeline project, it would provide only 68 bcm of gas in total, which is still less than half of Russia’s exports to Europe – nearly 160 bcm in 2013. Miller’s claim could be possible if the EU decreases its gas import from Russia by developing its shale gas reserves, increasing efficiency and investing more on alternative energy routes.

Another important aspect of this agreement is that CNPC gained 10 percent stake from the Rosneft’s subsidiary Vankorneft operating in the Vankor oil field. This is crucial because Russia usually allows foreign companies to operate only in underdeveloped fields. However, with this sale, Russia sold a stake from an operational field to China. This way, Russia found a short-term solution for its immediate cash need.

Although leaders from both sides emphasize the developing relations, the increasing imbalance between the two powers, as well as overdependence, makes Russia uncomfortable. Although these agreements are seen as advantageous by Russia in the short term, due to China’s insistence on lower prices with the declining of the oil prices, it can harm the Russian economy in the long run. Joseph Nye, in his analysis in the Project Syndycate, points out that “the gas deals amplify a significant bilateral trade imbalance, with Russia supplying raw materials to China and importing Chinese manufactures. And the gas deals do not make up for Russia’s lost access to the western technology that it needs to develop frontier arctic fields and become an energy superpower, not just China’s gas station.”

To conclude, it is obvious that cooperation with China would help Russia to relieve its economy in the short term. However, due to the challenges of realizing the second agreement, concerns of Russia and historical mistrust between the two powers, their cooperation has limits. However, the current conjuncture has brought the two powers together for the time being. If the conditions change, the winds may blow from the opposite side.

Yağmur Erşan, a research assistant in USAK Energy Security Studies, is currently a co-editor of the usak.org.tr. She has received her Bachelor’s Degree at Middle East Technical University in International Relations Department and still continues her graduate studies at the same university. Her main areas of interests are energy, Asia-Pacific region, and Chinese domestic and foreign policy.