By Kavaljit Singh

The Greek debt crisis saga continues with no resolution in sight. As expected, the European leaders rejected a last-minute proposal by Alexis Tsipras, Prime Minister of Greece, requesting an extension of the bailout program that expired on 30th June and seeking a new €29.1 billion bailout package that could have covered country’s debt obligations over the next two years.

The rejection led the country to default on its €1.6 billion loan repayment to the International Monetary Fund. Greece is the first developed country to default to the IMF. Even though the IMF does not use the term default, it will now classify Greece as being “in arrears” and the country will only receive funds in future once the arrears are cleared.

After several rounds of protracted negotiations in Brussels, Greece had rejected the anti-austerity conditions contained in the bailout package prepared by the troika (European Commission, European Central Bank and the IMF). The troika demanded substantial cuts in pension and wages besides overhauling value-added tax as a precondition for releasing the remaining funds from the bailout package which expired on 30th June. Disappointed over the rigid stand taken by troika, on 27th June, Mr. Tsipras announced a referendum to decide whether or not Greece should accept the bailout conditions. The referendum will take place on 5th July.

By announcing a referendum, the Greek government has put the ball in people’s court. It is hard to predict the outcome of forthcoming referendum. It is likely that a No vote would strengthen the bargaining power of the current government which came to power on anti-austerity platform in January 2015. While a Yes vote would make the government’s position untenable and probably lead to general elections.

Capital Controls

On 28th June, the Greek government imposed capital controls and other regulatory measures to maintain liquidity and stability in the banking system. These include:

- All banks in the country will remain closed for a week (June 29- July 6, 2015).

- An individual can withdraw up to €60 per card a day from ATM.

- The foreign bank cards are exempted from this daily limit.

- The transfer of money to outside Greece will require approval from the official authorities.

- A specialized agency will deal with urgent payments that cannot be met through cash withdrawals or electronic transactions.

The Accumulation of Public Debt

No discussion on Greek debt crisis would be complete without analyzing how the country’s public debt got accumulated over the years. In 2004, the country’s public debt was €183.2 billion. By 2009, it reached as high as €299.5 billion, or 127 percent of country’s GDP.

Currently, Greece’s public debt stands at €323 billion, nearly 175 percent of country’s gross domestic product. Both the critics and supporters of Greek’s government admit that such a high debt-GDP ratio is unsustainable. The current government is seeking substantial write-off of country’s debt so as to put the country back on a growth trajectory. While seeking debt relief for Greece, several economists and legal experts have referred to London Agreement in 1953 which gave generous debt relief to West Germany by writing off its 50 percent of debt, accumulated after world wars. This debt relief was one of the key factors which enabled the reemergence of Germany as a world economic power in the post-war period.

In 2015, the Greek Parliament set up a Truth Committee about the Public Debt to investigate how country’s foreign debt got accumulated from 1980 to 2014. The Committee has recently released a preliminary report which states that Greek public debt is largely illegitimate and odious. I would earnestly request readers to read this report as it confronts several popular myths associated with the Greek public debt. According to the report, the increase in debt before 2010 was not due to excessive public spending but rather due to the payment of extremely high rates of interest to creditors and loss of tax revenues due to illicit capital outflows. Excessive military spending also took place before 2010.

More importantly, the report reveals how the first loan agreement of 2010 was used to rescue the Greek and other European (especially German and French) private banks. The loan agreements of 2010 (and 2012) helped private banks and creditors to offload their risky bonds issued by the Greek government. In simple words, the debt of the private banks was transformed into public sector debt via bail-outs. As pointed out by Tim Jones of Jubilee Debt Campaign, it is not the people of Greece who have benefitted from bailout loans from the troika but the European and Greek banks which recklessly lent money to the Greek government in the first place.

Out of €254 billion lent to the Greek government by troika since 2010, only 11 percent have been spent to meet government’s current expenditure. Of course, previous governments of Greece are equally responsible for spending beyond its means and falsifying its public accounts.

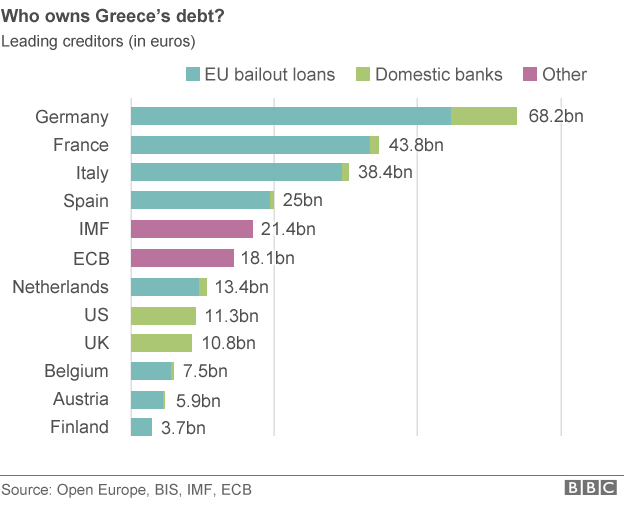

Who owns Greece’s public debt? Currently, close to 80 percent of Greece’s public debt is owned by public institutions — primarily from the EU (member-states, ECB and EFSF) and the IMF (see chart below) The rest is owned by private creditors.

Austerity Caused a Humanitarian Crisis

The social and economic consequences of austerity measures imposed by troika on Greece have been devastating. Since 2010, Greece’s GDP has fallen by 25 percent and unemployment rate is 26 percent. The youth unemployment rates are at an alarmingly high level. Currently, over 56 percent of young people in Greece are without a job and there are more than 450,000 families with no working members. After five years of fiscal adjustment and economic hardship under the austerity program, Greece’s major indicators (including GDP, employment and incomes levels) are still far below the pre-crisis levels.

The welfare spending cuts proved to be counter-productive. As pointed out by Ozlem Onaran of University of Greenwich: “The wage and pension cuts and fiscal consolidation led to lower GDP, tax losses, and higher public debt. Our estimates show that the fall in the wage share alone has led to a loss in GDP by 4.5%, and a 7.80% point increase in the public debt/GDP ratio. The fall in wages alone explains more than a quarter (27%) of the rise in the public debt/GDP ratio in this period. The conditionalities of the memoranda have not only been counterproductive in terms of its aims regarding debt sustainability, but also engineered a humanitarian crisis.”

Many legal experts argue that the harsh austerity program imposed by troika could potentially pose a violation of human rights. According to Ilias Bantekas, Professor of International Law at Brunel University Law School, “The measures imposed against the Greek people were wholly antithetical to fundamental human rights as these stem from customary international law, multilateral treaties and the Greek constitution. Consequently, these ‘loans’ were held to be odious, illegal or illegitimate.”

It is pertinent to note that not just in Greece, the austerity programs also failed to yield positive results in Cyprus, Spain and Ireland.

Grexit: Pain and Gain

What would happen if Greece abandons or is forced to exit the euro? In the short-term, it would certainly entail greater uncertainty and economic hardship. A massive capital flight by the elites along with collapse of banks and businesses which have borrowed in euros cannot be ruled out. The payments of salaries and pensions could also be delayed for months.

The social and economic consequences could be disastrous for Greek economy and its people if the transition from the euro to a new national currency (possibly drachma – its old currency) is badly managed. Hence, the transition should be well-planned and properly implemented with popular support.

There is a growing consensus that a massive devaluation of drachma would help in increasing domestic demand and improving the prospects of economic recovery. A weak drachma would make Greek exports more competitive and its tourism more attractive and therefore would open up new opportunities to enhance exports and encourage more tourism over the long-term. Exports account for nearly 30 percent of its GDP. Because of a weak new drachma, the demand for domestic goods would increase as imports will become more expensive thereby boosting the domestic demand which, in turn, would also encourage greater domestic production and create more jobs for Greek people.

In addition, Greece will also regain its independent monetary policy and fiscal space to set policies in tune with its own economic needs instead of those of Eurozone economies. Needless to say, a small country like Greece (representing less than 2 percent of EU’s GDP) should never have joined the flawed monetary union in the first place.

Wider Ramifications for Europe

Greece leaving the euro will have serious economic ramifications for the rest of Europe. If Greece leaves the Eurozone, the threat of financial contagion to other weak Eurozone economies (such as Portugal, Ireland, Spain and Italy) looms large and subsequently these economies may as well exit the euro. Not only such a move would weaken the Eurozone but, more importantly, it would spell the end of the single currency experiment and the larger European project towards greater economic integration.

Besides, one cannot ignore the fact that the euro may face massive devaluation if international investors liquidates their European assets and investments en masse.

Furthermore, there are human and geo-political ramifications which are not sufficiently understood by European leaders. How will the EU cope with the influx of migrants from North Africa who enter Europe (via Mediterranean route) without the active cooperation of Greek government?

Technically speaking, an exit from euro does not mean an exit from the EU. A Greek veto on extending sanctions against Russia over Ukraine would further weaken the European strategy to isolate Russia.

The observation made by many commentators that Grexit would isolate the country from the world economy is highly misplaced. Greece can explore new economic partnerships and build strategic alliances with Russia, China and other developing world. Given its favourable geo-economic location in Southern Europe, Greece can emerge as an important regional energy distribution hub. Greece has already launched discussions with Russia to build a gas pipeline to Greece via Turkey and then to Europe. This pipeline could bring immense benefits to Greece’s economy in terms of new investments and jobs. Greece is currently considering joining the New Development Bank (NDB) which was set up in 2014 by BRICS. Becoming a member of Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank is another possibility.

Needless to say, the European leaders need to act more like statesmen as the European Union is founded on the values of respect for democracy, equality, human rights and solidarity.

The Broader Meanings of ‘No’ Vote

Finally, the Greek citizens have delivered a resounding ‘No’ to bailout conditions demanded by creditors in a referendum held on 5th July. The referendum was announced by Greece’s Prime Minister, Alexis Tsipras, on 27th June after bailout talks with the creditors failed. The referendum asked voters to decide “whether to accept the outline of the agreement submitted by the European Union, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund at the Eurogroup of 25/06/15.”

The government-backed ‘No’ side won with 61.31 percent of votes, while ‘Yes’ got the remaining 38.69 percent. Further, not a single electoral district of Greece voted for ‘Yes’. No one in Greece had predicted such a massive victory for ‘No’ vote. Most opinion polls had predicted a tight contest with ‘No’ side winning by a slim margin.

Does a ‘No’ victory mean Greece leaving the euro and the EU? Not exactly. As pointed out by PM Tsipras, “This is not a mandate of rupture with Europe, but a mandate that bolsters our negotiating strength to achieve a viable deal.”

Undoubtedly, the landslide victory in the referendum has greatly strengthened the bargaining power of the current government with creditors. The impacts of the austerity measures imposed by the international creditors have been catastrophic. The Syriza-led government, which came into power on an anti-austerity platform in January 2015, has resisted pressure to implement harsh austerity programs that affect the elderly and the poor.

Another positive outcome of the referendum is that the opposition parties have also given support to the Syriza-led government to negotiate a new deal with creditors. In many important ways, the decisive referendum has brought political stability in Greece which has witnessed four elections in five years.

A New Deal for Greece

In the current circumstances, a new deal is challenging but still feasible. Both sides need to realize the sense of urgency to pursue a realistic agenda. The negotiations between Athens and Brussels should resume immediately in order to avoid a major financial meltdown.

On their part, the leaders of Eurozone should accept a compromised deal to end the impasse. They should not insist that any special privileges to Greece would encourage other potential rule-breaking eurozone countries. The costs of a Grexit are high not only for Greece but also the entire Europe in terms of wider economic and geo-political implications.

It is important to note that the IMF in its preliminary draft debt sustainability analysis (dated June 26, 2015) has sought substantial debt reduction along with extended concessional financing for Greece. This IMF analysis specifically points out that Greece needs “a significant haircut of debt, for instance, full write-off of the stock outstanding in the GLF facility (€53.1 billion) or any other similar operation.” The Greek Loan Facility (GLF) consists of bilateral loans pooled by the European Commission.

A new deal is feasible if the European leaders realize the true importance of ‘No’ vote. The message of Greek referendum is loud and clear: harsh austerity measures imposed by the EU lack democratic legitimacy. And the debt relief should not be treated as a taboo.

Hence, keeping the wider interests of the European project in mind, its political leadership should adopt a more flexible approach towards Greece based on the principles of democracy, human rights, cooperation and solidarity. After all, the financial rules are meant to serve the people, not the other way around.

In return, Greece should also undertake policy measures to check massive tax evasion by oligarchs and streamline its public finances. Needless to say, the Greek government should be given a fair chance to put its house in order. This entails patience on the part of official creditors.

Kavaljit Singh is Director of Madhyam, a policy research institute based in New Delhi.