Egypt: The catalyst for a new Eastern Mediterranean gas hub?

By Simone Tagliapietra and Georg Zachmann

The recent discovery of the large Zohr gas field in offshore Egypt – the largest ever made in the Mediterranean Sea – might completely change the regional gas outlook.

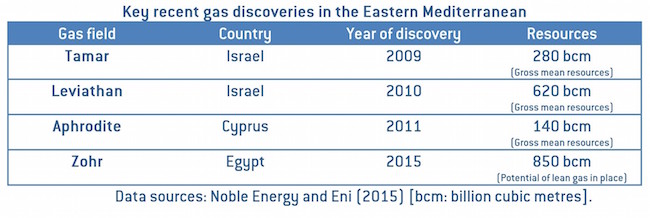

In recent years the Eastern Mediterranean has been a hot topic in international gas markets. Interest in the area peaked when three large fields were discovered between 2009 and 2011: the Tamar and Leviathan fields off the shore of Israel and the Aphrodite field off the shore of Cyprus. The resources of these three fields are currently estimated at about 1000 billion cubic metres (bcm), compared to about 2800 bcm of gas resources in the EU’s largest gas field.

To exploit this potential, a number of export options where progressively discussed, from pipelines (to Turkey or Greece) to liquefied natural gas (LNG) plants (in Cyprus, Israel and Egypt).

Analysts have expressed hopes that the new gas discoveries might not only strengthen the energy cooperation in the area but also pave the way for a new era of economic and political stability in the region.

However, the high initial expectations were largely muted over time. In Israel a long-lasting internal political debate on the management of the gas resources created a climate of uncertainty that contributed to the delay of key investment decisions. In Cyprus -where the gas discovery was welcomed as a godsend gift to relief the country from its financial troubles- the initial enthusiasm was cooled-down by successive downward revisions of the expected resources. These developments raised skepticism on the general idea that the Eastern Mediterranean might become a gas-exporting region.

All of a sudden, the initial expectations have been revived by the recent discovery of the large Zohr gas field in offshore Egypt. Considering its size, this discovery -the largest ever made in the Mediterranean Sea- might indeed completely change the regional gas outlook.

In this article we argue that regional geopolitics is the factor that will ultimately define whether this new development would remain confined to Egypt or would systemically impact the overall Eastern Mediterranean region.

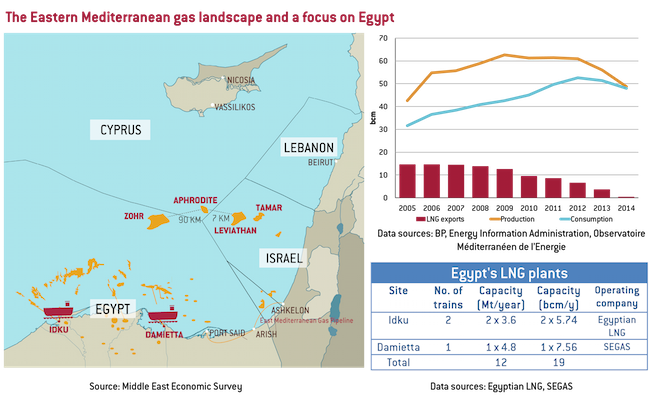

If there is a certainty about Zohr, it is that its development will primarily serve the Egyptian domestic market. Due to a rapid decline in production the country has increasingly struggled to meet its domestic demand. As a result Egypt even started to import LNG in 2015 through two floating storage and regasification units (FSRU) leased for five years. Accordingly, Egypt’s LNG exports dropped from a starting level of about 15 bcm/year in 2005 to almost zero in 2014, leaving the country’s two LNG plants completely idle. With a potential 20 year-plateau production level of 20-30 bcm/year Zohr would thus be a major relief for Egypt’s constrained gas market.

Zohr could be the first of a new string of gas discoveries offshore Egypt. International oil and gas companies have already started to increase operations in the area, and if Zohr and other offshore fields reach their full potential in the 2020s, Egypt might by that time again become an LNG exporter.

However, the impact of Zohr could well go beyond Egypt’s boundaries, due to its geographic location and infrastructure.

Zohr is located only 90 kilometers (km) away from Aphrodite, which in turn is only 7 km off from Leviathan. This proximity could allow a coordinated development of the fields and thus the creation of the economies of scale needed to put in place a competitive regional gas export infrastructure.

Egypt already has in place a 19 bcm/year LNG export infrastructure in Idku and Damietta that currently sits idle. This would allow to export any volumes from Zohr and other domestic fields not used in the domestic market. Given the growing domestic demand in Egypt, it is fair to assume that some export capacity would be left for Israeli and Cypriot gas – if it could be brought to the Egyptian terminals. As both LNG plants can be expanded Israeli and Cypriot developers would have a flexible outlet.

For Israel and Cyprus, cooperating with other players in the region is crucial. Building the export infrastructure and developing the fields is a circular problem: if there are political or commercial risks that no export infrastructure will be in place when the production starts, a lot of money will be lost. If the field underperforms compared to expectations, expensive export infrastructure (the Cypriot LNG Vasilikos project is estimated to cost USD 6 billion) will sit idle. Consequently, bringing together an underused and scalable export infrastructure with several promising fields could be the key to unlocking untapped regional potential.

So, Egypt seems to hold the keys of the Eastern Mediterranean gas future. It could decide to proceed alone by exporting the gas volumes that will progressively become available on top of the domestic demand, or it might decide to proceed together with Israel and Cyprus, by creating a new Eastern Mediterranean gas hub based on its existing exporting infrastructure.

Creating a new Eastern Mediterranean gas hub would present benefits for all players involved, allowing Egypt to enhance its role in the region and secure revenue from a transit scheme, and Israel and Cyprus to fully exploit their gas reserves. It would also present an opportunity for Europe, where gas imports requirements will grow post 2020 due to declining domestic production and expiration of long term contracts with Norway and Russia.

Albeit commercially sound, the realization of a new Eastern Mediterranean gas hub will ultimately depend on foreign policy considerations and domestic politics in Israel and Egypt. Public opinion in both countries will be critical of tight-cooperation in such a strategic sector.

For its part, the EU should support a regional cooperation scheme aimed at developing an Eastern Mediterranean gas hub, for both energy policy and foreign policy considerations. In terms of energy policy, this initiative could provide much-needed substance to the long-lasting EU gas supply diversification strategy. In terms of foreign policy, this initiative could allow international collaboration in an area that otherwise currently presents very few opportunities for cooperation.

Simone Tagliapietra joined Bruegel in April 2015. He is Senior Researcher at the Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei in Milan and Visiting Researcher (Non-residential) at the Istanbul Policy Centre at Sabanci University in Istanbul. He is an expert in international energy issues, with a record of several publications covering the international natural gas markets, the EU energy policy and the Euro-Mediterranean energy relations, with a particular focus on Turkey. Georg Zachmann joined Bruegel in September 2009. He is also a member of the German Advisory Group in Ukraine and the German Economic Team in Belarus and Moldova. Prior to that he worked at the German Ministry of Finance and the German Institute for Economic Research in Berlin. Georg Zachmann’s work at Bruegel focuses on energy and climate change issues. He has worked on the European emission trading system, the European electricity market and European renewables policy.