By Rene Wadlow

The Global Citizenship Commission (GCC) under the leadership of the former UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown presented its report The Universal Declaration of Human Rights in the 21st Century to the United Nations on 18 April 2016.[1]

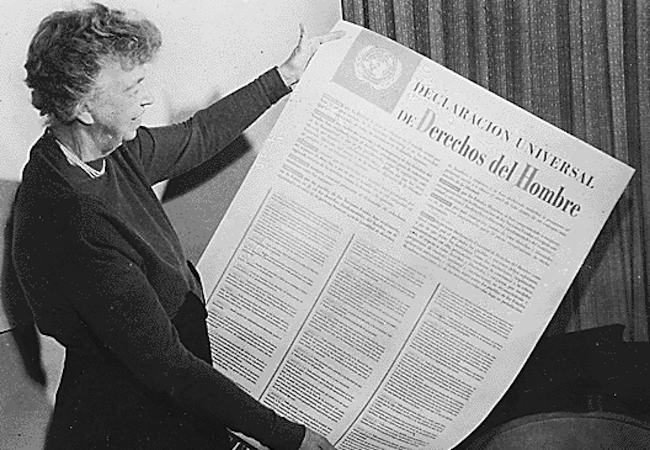

The Global Citizenship Commission was created “to illuminate the ideal of global citizenship. What does it mean for each of us to be members of the global society?”[2] Human rights are the foundation of the global society. The principal aim of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was to create a framework for a world society that was in need of universal codes based on mutual consent in order to function. The early years of the United Nations was characterized by the division between the Western and Communist conceptions of human rights, although neither side called into question the concept of universality. The debate centered on which rights, political, economic and social were to be included.

In the 1960s with the entry into the UN of a large number of African States which had not been present when the UDHR was proclaimed in 1948, there were discussions as to whether new States were bound by the UDHR values adopted before they were independent. By and large, consensus was reached on the universality of all the human rights set out in the UDHR. This universality was clearly reaffirmed in the 1993 Vienna Declaration of the World Conference on Human Rights in which nearly all UN Member States took part.

In 1948, the members of the UN Commission on Human Rights saw the human rights process as a three-step effort. First was the proclamation of the general principles which was the UDHR. The second step was to be the codification of these principles into laws both at the world and at national levels. The third step was to be some form of implementation through reports and observation, possible complaints procedures and ultimately some form of enforcement or sanctions. In 1948, it was not clear how the second and third steps should be carried out.

In practice, through the leadership of UN Secretariat members of the UN Centre for Human Rights and active representatives of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), there has developed a rich texture of human rights conventions with 10 “treaty bodies” which receive reports on the application by governments of the human rights treaties they have ratified.

The Commission on Human Rights has now been transformed but largely unchanged into the Human Rights Council. The Commission began the practice, continued by the Council, of naming “Special Rapporteurs” on specific issues such as “States of Emergency” or on specific country situations where there was broad agreement that there were persistent human rights violations.

Largely through the efforts of NGO representatives helped by UN Secretariat members but who must keep a “low profile”, there has been progress made both on issues and on bringing attention to vulnerable people. The Global Citizenship Commission highlights these advances, but as only one member of the Commission came from the NGO world, the NGO representatives role is somewhat lost in the vague terminology of “civil society”.

I would stress seven areas which have become part of ongoing UN human rights work that owe their existence to NGO efforts in the Commission on Human Rights:

1) Awareness of the rights and conditions of indigenous and tribal populations;

2) Torture;

3) Death penalty;

4) Conscientious objection to military service;

5) Child soldiers;

6) Systematic rape in armed conflicts;

7) The Right to Religion and Belief.

Beyond the UN human rights bodies, other parts of the UN system have played an important role: the International Labour Organization on the abusive work of children and youth, UNICEF on the rights of children. As the Global Citizenship report stressed, it would be good to have more cooperation within the UN system. This is a repeated theme of all reports on the functioning of the UN, but then, it could be said of national governments as well.

Much of the Global Citizenship report is devoted to the analysis of the way the UN has met past challenges and is a good overview for those who have not participated directly. The report calls in a general way for improvements. “The international community needs a toolkit of governmental and multilateral responses to rights violations that is more legitimate and sophisticated than what we have today and which relies on mechanisms other than the use of force.”

The GCC report highlights two new challenges:

1) discrimination due to sexual orientation;

2) migration-refugee flows due to both short-term armed conflict and longer-term consequences of climate change.

On the first issue of discrimination due to sexual orientation, representatives of NGOs have already been active. There has been real progress from the mid-1980s when the issue had been first raised and then “swept under the rug” due to strong opposition from a number of States. Now, UN Secretariat members have taken the lead. There is still much to be done, especially in changing attitudes at the individual and local levels, but I think that the direction toward inclusiveness has been set.

Issues of migration and refugees go beyond what NGOs can do alone, although NGOs have been active on both refugee and climate change questions. On 19 September, at the start of the UN General Assembly, there will be a one-day Summit on migration issues at the UN in New York. NGOs should be able to make migration-policy suggestions in advance and to raise the issue of “statelessness” which is increasingly a result of migration.

The Global Citizenship Commission with its secretariat at New York University Global Institute for Advanced Study has set out a clear overview of the past and has highlighted some of the new challenges − a useful alert for those of us working on global issues and a call for an increased number of co-workers.

Notes

- The study is available in print from the UK firm Open Book Publishers (www. Openbookpublishers.com) and can be downloaded in pdf at no cost.

- The Global Citizenship Commission follows the pattern of earlier independent commissions often best remembered by the individuals who headed them: Pearson, Brandt, Palme, Brundtland, Carlson/Ramphal. See Ramesh Thakur, Andrew Cooper, John English (Eds). International Commissions and the Power of Ideas (Tokyo: United Nations University Press, 2005, 317pp)