By Maariyah Siddique

2234 people in the last 17 months have contracted HIV because they were so sick they needed blood.

The National Aids Control Organisation (NACO) has revealed the information in response to an RTI petition filed by information activist, Chetan Kothari.

According to the RTI reply, Uttar Pradesh makes up the highest number of patients infected with HIV through transfusion of contaminated blood in hospitals with 361 cases, followed by Gujarat with 292 cases and Maharashtra with 276 cases. The Capital Delhi alone has registered 264 cases as of yet. States like Meghalaya, Tripura and Sikkim have zero reports.

Kothari says he was “shocked” by the information his query brought out. He added, “This is the official data, provided by the government-run NACO. I believe the real numbers would be double or triple that.”

As per the HIV Estimation Report (2015), 21.17 lakh people are presently living in the country with HIV/AIDS. With this, India constitutes the world’s third largest population of people affected by HIV. The other two leading the numbers are South Africa (68 lakhs) and Nigeria (34 lakhs).

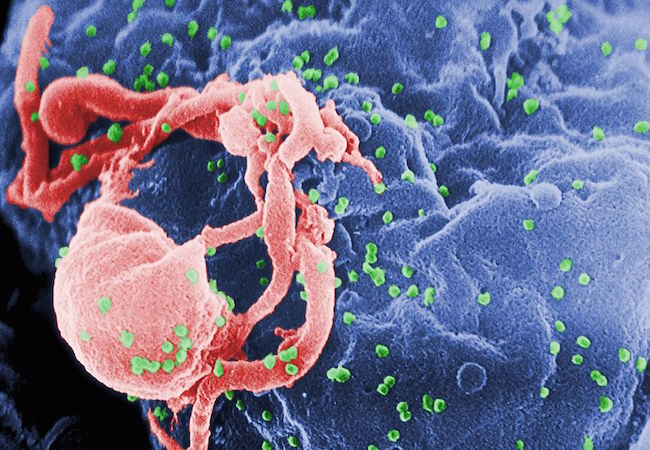

Despite many efforts, blood transfusion remains a source of HIV infection globally, with its incidence varying between high-income and low-income countries. In India, shortage of several million blood units occurs every year, with only 1% being the rate by which HIV infection through blood transfusion has decreased lately.

According to the Indian Journal of Anaesthesia, dated 2014, Volume 58, Issue 5, the government has set standards for safe blood transfusion but these suffer a heavy lack of proper implementation.

“There are private labs which also conduct these tests but they charge hefty amounts. Therefore, it is not possible for poor people to get it done,” said Kothari.

The law in India makes it mandatory for hospitals to screen both the donors and the donated blood and check for HIV, hepatitis B and C, malaria, syphilis, and other such infections.”But each such test costs 1,200 rupees and most hospitals in India do not have the testing facilities. Even in a big city like Mumbai, only three private hospitals have HIV testing facilities. Even the largest government hospitals do not have the technology to screen blood for HIV,” said Kothari.

A larger section of people coming from the lower strata donates blood to earn immediate money. Even though payment to blood donors is banned in India, this section makes up as the fuel to a lucrative blood business in the black market.

Other than blood banks, hospitals often ask families of patients to get donors so they can stock up for a later need of blood transfusion. Ideally, all blood banks must examine the donor’s medical history and the presence of any chronic illness. They must compulsorily counsel the donors and finally check the donated blood during the entire process of blood donation. There is also a ‘window period’ when a donor might not test positive for weeks even after being affected by HIV. However, there are tests to reduce the same and accelerate the donation procedure, but costs are high.

There are state-run and national level NGOs that volunteer and set up blood donation camps across with the help of social service enthusiasts and prominent activists. “I am required to look for at least 18-19 donors a day as an intern at the primary level,” said Nidhi Tripathi, who works with The Saviour NGO in Kolkata. The organisation has arranged “over 500 donors in an emergency, registered over 20,000 people as emergency blood donors and conducted many blood donation camps in public.”

India’s blood donation system has recently suffered a major setback due to reduced funding and growing self-approbation. “More blood donation campaigns with a stringent safety-checking mechanism needs to be promoted,” says Dr N. Alam, a Homeopath physician, based in Patna.

According to officials, the decrease in the number of newer infections has led to funding being reduced over the years. Also, in the last two years, widespread deficiencies of stocks of important drugs and testing kits have resulted due to bureaucratic delays having “little or no accountability.”

While it becomes absolutely essential to strengthen the screening process of blood donors, it is also vital for the government to pay heed to funds in the health sector.

“The central and the state government need to coordinate and bring out a measure so that these things are made available to the poor,” said Kothari.

Maariyah Siddique is a student of M.A in Convergent Journalism at A J Kidwai Mass Communication Research Centre, Jamia Millia Islamia.