By Hazrat Hassan

The head office of Sheyang Rural Commercial Bank is an encouragingly solid building. Its grey stone façade and arched doorways convey a feeling of prosperity, a splash of high finance in this small county town in eastern China where grain fields nip at the edges of factories. But look a little closer and you will still find a couple of scars from the bank’s near-collapse two years ago. One is a digital sign running in a loop over the entrance: “Treasure your hard-earned money, avoid the temptation of high returns, and stay far from illegal financial schemes.” The second is a prize draw for cars, a pair of gleaming white Kais on a red platform outside the bank. “Deposit 100,000 yuan today and win the chance to drive a new car home,” blares the announcement. The bank is fighting to attract customers because it knows all too well what it is like to lose them. [1]

Decades of heady growth had put money into the pockets of Sheyang’s residents. But China’s big banks had little time for the countryside. Farmers who wanted to buy homes or start companies struggled to get loans. Illegal lenders stepped into the gap; they collected cash from those with idle savings and lent it out, often at double-digit interest rates. Business boomed. As locals put it, the lenders sprouted up like bamboo shoots after a spring rain—until a few years ago, when a harsh wind uprooted them. The economy was slowing and investment plans relying on superfast growth fell apart. Borrowers could not pay back what they owed. The unregulated lenders started defaulting on their depositors. Panic spread. In March 2014 it was rumored that even Sheyang Rural Commercial Bank, which is owned by the government, was low on cash. [2]

This was enough to spark China’s first bank run in years. Crowds gathered outside its branches, waiting for hours in the drizzly chill to get their money out. Bank managers stacked up bricks of 100-yuan notes (China’s largest denomination) to show they had sufficient cash. Yet fear travelled like a virus, infecting another nearby bank. On the third day of the panic the China Banking Association, an industry group, entered the fray and declared the rural banks to be healthy—in effect, pledging to stand behind them. That ended the run. It had taken the full weight of the nation’s banks acting in concert to restore calm. [3]

One county’s travails might not seem worth making a big fuss about. After all, the deposits at Sheyang Rural Commercial amount to just 13.5 billion yuan ($2.1 billion), barely 0.01% of the total in banks nationwide; and the problems were successfully contained. [4]

Sheyang’s bank run is just one of a series of problems to reveal cracks in the Chinese financial system in recent years. Others include a cash crunch in 2013, a wave of shadow-banking defaults in 2014, a stock market collapse in 2015 and a surge of capital flight at the start of 2016. Underlying it all, China has seen a dramatic rise in debt, from 155% of GDP in 2008 to nearly 260% at the end of last year, according to an estimate by The Economist. Few countries have gone on borrowing binges of that magnitude without hitting a crisis. [5]

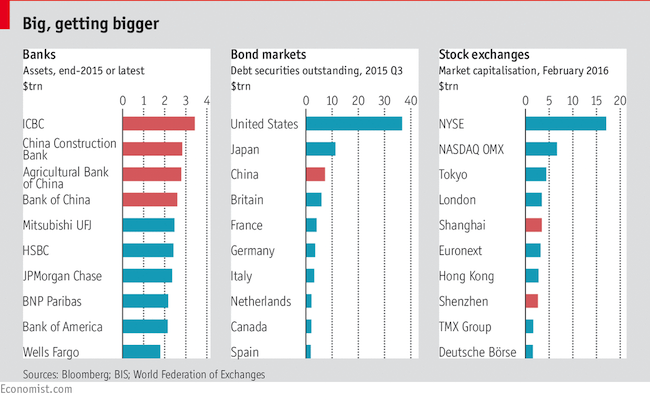

The scope for potential trouble in China is immense. Its banking sector is the biggest in the world, with assets of $30 trillion (see chart), equivalent to 40% of global GDP. China’s four biggest banks are also the world’s four biggest. Its stock markets, even after the crash, together are worth $6 trillion, second only to America’s. And its bond market, at $7.5 trillion, is the world’s third-biggest and growing fast. [6]

A cocoon of regulations limits direct foreign involvement in China’s financial system, but connections are deepening by the day. Given its economic heft, serious problems could easily dwarf the global consequences of any previous emerging-markets crisis. Even the mild yuan depreciation at the start of this year (1% against the dollar in one week) sent shock waves around the world, upsetting stocks, currencies and commodities. Just imagine the effects of a big one. [7]

All these controls have allowed China systematically to gather up its people’s savings in its banks and use the money to build infrastructure, factories and homes, fuelling economic growth. When lending has gone badly wrong, as it did in the 1990s, the state has recapitalized its banks and fired up the lending machine again. Not best practice for an advanced economy—but, as Taiwan and South Korea have shown, it can be a supremely effective model for development. Even so, China’s status quo cannot be sustained forever. Returns on capital are declining. It now takes nearly four yuan of new credit to generate one yuan of additional GDP, up from just over one yuan of credit before the global financial crisis. As the population ages and the economy mature, growth is bound to slow further. [8]

At the same time, bad debts from the past decade’s lending binge are catching up with banks. Given slower growth, it will be tougher to clean them up than it was 15 years ago, when the country was booming. Moreover, the edifice of control is getting shakier: shadow finance is eating away at the power of state-owned banks, and the capital account has sprung leaks that regulators are struggling to plug. [9]

China has, in other words, reached a level of development where it needs a more sophisticated financial system, one that is better at allocating capital and better suited to the market pressures now bubbling up. The government pays lip service to this, and indeed some reforms point in the right direction: it is deregulating interest rates; the exchange rate, though still managed, is more flexible; defaults are chipping away at the notion that the state will guarantee every investment, no matter how foolish. [10]

References

- “China and the Coming Debt Bust.” RealClear, 2015.

- Curran, Enda. “China Faces a Debt Crisis.” Bloomberg, 2016.

- G, Fotis Plegas. “Explaining Greece’s Debt Crisis.” Explaining Greece’s Debt Crisis, 2016.

- HOUZE SONG, DEREK SCISSORS, YUKON HUANG. “Is China on a Path to Debt Ruin?” ChinaFile, 2016.

- Rabinovitch, Simon. “China needs to free up its financial system, even if it hurts.” The Economist, 2016.

- RICHARD VAGUE. “The Coming China Crisis.” Democracy, CHINAECONOMICS, 2015.

- Rosenfeld, Everett. “China’s debt: Worse than you think, but maybe not be a problem.” CNBC WORLD ECONOMY, 2016.

- Teamnearandl. “China: The coming debt bust and global crisis.” Financial, 2016.

- “The coming Debts Burst .” China’s financial system, 2016.

- Wikipedia. “Current and recent debt crises.” Debt crisis, 2015.