Syria: still not safe for Turkey

By Damien Dean

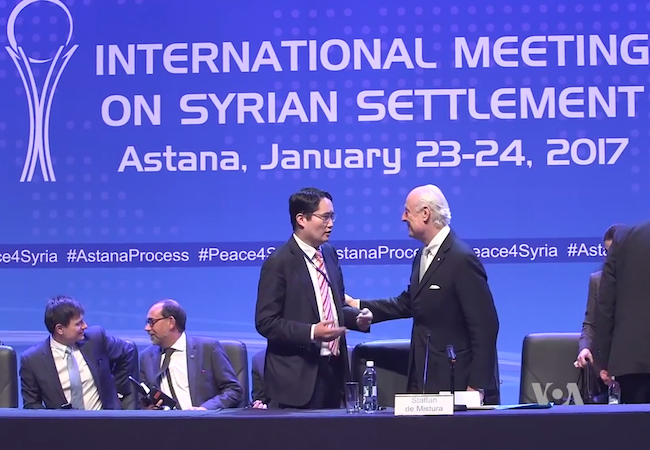

Having forcefully understood that the military solutions are far from being solutions, parties involved in the Syrian conflict convened for a meeting in Astana, the capital of Kazakhstan. The purpose was to set an agenda for solidifying the cease-fire brokered last December to stop the human suffering as well as to achieve the first meaningful step towards a political solution.

For the first time since the conflict began in 2011, the representatives of major actors and their proxies on the ground were invited to the meeting. The meeting spearheaded by Russia, Turkey, and Iran excluded some warring actors and elements.

ISIS was barred from the talks for obvious reasons. Jabhat Fateh al-Sham did not receive an invitation for its affiliation with Al Qaida. There appears to be no room for radical groups in the reconstruction efforts for Syria.

Likewise, Saudi Arabia and Qatar, staunch supporters of the rebel groups in Syria, were not invited due to the Assad regime’s consternation over their shared record of financing terrorism in Syria. Perhaps the most surprising member of those excluded from the meeting was the pro-Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) and its militia People’s Protection Units (YPG), which controls Kobane, Afrin, and Rojava cantons in northern Syria—formations that pose major security risks for Turkey. The Kurdish groups declared, before the meeting kicked off, that the results of the Astana meeting will not be binding for them due to their exclusion, blaming Turkey for sidelining them.

The other not-so-surprising surprise was the ambassadorial presence of the United States in the meeting. The US was represented by George Krol, the US ambassador to Kazakhstan. Such representative choice has been interpreted by pundits as a sign of the diminishing stature and influence of the US within the conflict. It is also possible, however, that the low-key presence of the States may well demonstrate that Trump’s roadmap for Syria is underway, and the new administration weighs possible options.

So far from what has been gathered from his words, Mr. Trump’s focus on radical Islam and its world-wide symbol ISIS gives hints about the new US policy towards Syria, especially after a recent interview with ABC News during which he revealed a safe-zone plan in Syria. This suggests that the US under the Trump administration will increase its efforts to combat ISIS while creating secure zones for civilians. Of course, creation and maintenance of such zones will be unwieldy for the US as it would necessitate a broad coalition that supports such endeavour, which is currently unavailable. Nonetheless contrary to lamentations about the only super power’s retreat from Syria, it seems the US is preparing to enter the Syrian picture again with different but perhaps more practical tools.

A very active US engagement in the conflict under the Trump administration will be detrimental for Turkey. In the fights against ISIS, which seems the top priority for Trump, the US will not have any shortage of allies as Russia and the PKK-related Kurdish factions will provide their services enthusiastically. The first Trump-Putin meeting over a phone call already indicated a tendency to create a coalition between Russia and the US against ISIS. As such there is a possibility that Turkey’s assistance against ISIS might not be demanded by the US to the level of Turkey’s expectation. With regard to the creation of safe zones, Ankara, which has been vocal about this for years, has found Trump’s suggestion a little bit untimely, as she is already enjoying her de-facto safe zone nearby the Turkish-Syrian border.

The fall of Aleppo last December has very much changed the course of conflict in Turkey. Deputy Prime Minister of Turkey Mehmet Şimşek at the recent Davos summit stated that “The facts on the ground have changed dramatically, so Turkey can no longer insist on a settlement without Assad, it’s not realistic.” These statements indicate that Turkey has acknowledged the presence of Bashar al-Assad in Syria’s future. Turkey’s turn in her Syria policy was both necessary and out of necessity. It was necessary as Turkey understood a reconciliation with Russia requires a collaboration, though not deeply, in the Syrian conflict as well. It was out of necessity because the Western support Turkey sought in Syria has never arrived.

The Astana meeting left the prospects of a political solution for Syria to another Geneva conference, which will be held this coming February. Let’s hope that all parties involved in this intractable conflict can soon concur around the least common denominator: the cost of human life.