By Arthur S. Guarino

While the United States economy is experiencing growth and more jobs are being produced, American workers are experiencing their wages falling behind. Economists and policymakers are deeply concerned that paychecks will shrink as corporate profits increase and economic growth continues.

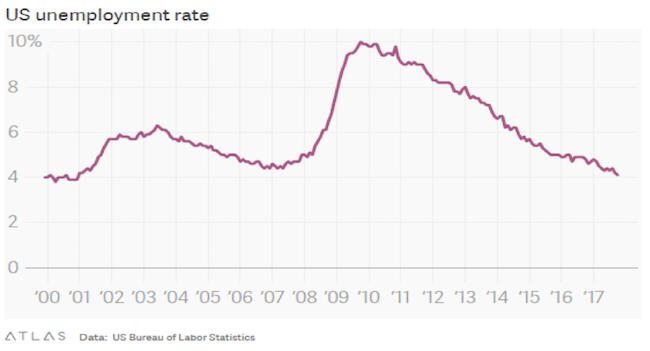

Despite the disappointing jobs number for December 2017 in which only 148,000 new jobs were created, the American employment picture is still looking good. Along with the unemployment rate reported at 4.1 percent and GDP rising 3.2 percent so far for the previous three quarters, the American economy is showing signs of continued strengthening. However, a key area that is experiencing disappointment and frustration for American workers, economists, and policymakers is the lack of wage growth. American workers are seeing that their paychecks are not participating in the nation’s expanding economic growth and this could have severe long-term consequences. That is, if wages do not show signs of growth how can workers not only afford their daily living expenses, but be able to purchase a home, new car, or send their children to college.

The current situation

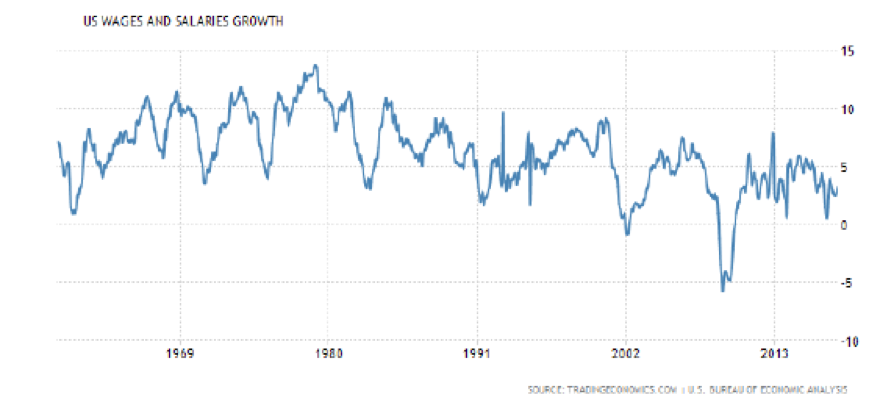

While the current situation for American workers seems quite bleak, the origins of this dilemma actually started in the 1970’s. According to a study by the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), wage decline and stagnation could be attributed to starting in the late 1970’s, specifically 1979. The EPI reported that middle-wage workers saw their hourly earnings actually stagnate since they were increasing at approximately 6 percent between 1979 and 2013, or less than 0.2 percent annually. The EPI study also noted that the wages of this group were either flatlining or suffering a decline in the decades of the 1980’s, 1990’s, and 2000’s.

Low-wage workers suffered even more, as the EPI reported that they saw their wages drop 5 percent between the years 1979 to 2013. The troublesome sign here is that the consumer price index (CPI) was, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), at an average rate of 3.25% annually. For these American workers, they witnessed their incomes drop precariously as prices for food, housing, and other staples of daily living continued to climb.

One could argue that the lack of education or proper skills contributed to the dilemma of middle-wage and low-wage workers. But according to the EPI report, this is not necessarily so. It was found that in 2013, even adjusted for inflation, young college graduates saw their hourly wages at a lower rate than in the 1990’s, regardless of whether they were male or female. In 1998, the real average hourly wage of a young college graduate was $18.00, while in 2013 it was $16.99.

While certain segments in the American economy have seen an increase in wages, such the health care industry, earnings for manufacturing workers have fallen. According to the National Employment Law Project (NELP), blue-collar manufacturing workers are seeing dangerous drops in their wages. NELP reported that real wages for such workers dropped by 4.4 percent from the years 2003 to 2013, exceeding by 300% in the earnings decline for all workers.

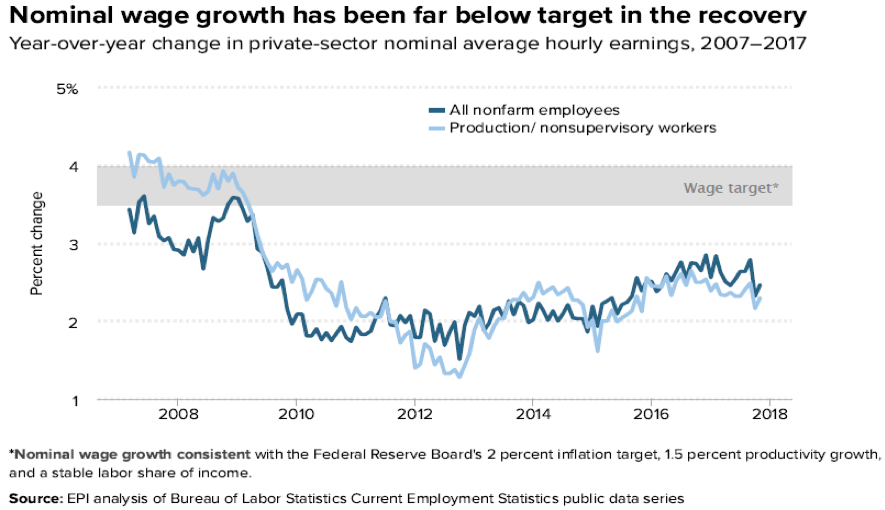

Most recently, the fall in wages seems only to be getting worse. In November 2017, the BLS reported that real average hourly wages for all employees dropped 0.2 percent from October to November, on a seasonally adjusted basis. The same BLS report showed that real average hourly earnings for all employees on private non-farm payrolls dropped from $10.77 in September 2017 to $10.72 in November 2017. A year earlier, in November 2016 the real average hourly earnings were $10.70. The plight for manufacturing and production workers is worse. The real average hourly earnings for manufacturing and production workers in November 2016 was $9.20 and stayed the same exactly one year later in November 2017. However, the CPI in November 2016 was 236.24 while in November 2017 it increased to 241.788. In other words, inflation increased in one year while the hourly wages for manufacturing and production workers remained stagnant. In sum, the situation for American workers is dire and shows no sign of improving.

Why is it occurring

There are a number of reasons why American worker’s wages are falling and they all come together to form a perfect storm effect to explain this dilemma.

Rise of globalization: The ability for American consumers to purchase cheaper products from overseas manufacturers has increased dramatically in the last thirty years and this ultimately means problems for workers in the United States. American consumers are more concerned about paying less for products that will give them the same quality and satisfaction they expect. However, it also means competition from overseas as well as the opening of borders and more trade than ever before. In order to remain competitive, American companies must either sell their products at cheaper prices while still maintaining the quality consumers expect and keeping their same level of profit margins or move their operations overseas. For those firms opting to keep their base of operations in the United States they must either streamline their production methods or lower wages, or do both. This places American workers between a rock and a hard place: work longer hours at their present jobs and take a pay cut or work for the same wages over an extended time period. Either way, American workers are seeing their wages either fall or remain stagnant due to globalization.

Decline in union membership: With the power of a union fighting for its members, workers have the chance to see their wages increase and keep pace with inflation. However, just the opposite has been occurring: along with the drop of union membership there has been a decrease in wages. At least with the representation of a union, workers have more bargaining power and a better chance of wage increases over time. The drop of union membership has been significant. In 1956, approximately 28 percent of the working population were union, but membership in 1983 decreased to 16.8 percent of workers in the private-sector and dropped again in 2016 since representation is only 6.4 percent. Unless there is a significant increase in union membership in the next ten years, then anti-worker tactics such as discouraging increases in the minimum wage or the salary threshold for overtime pay will only gain further traction among employers and further drop wages.

The Great Recession of 2008-2009: The fallout of Great Recession of 2008-2009 reverberates today among American workers. The Great Recession saw unemployment reach 10 percent at one point and that long-term unemployment witnessed dizzying heights. Compounding these factors was that companies made wholesale changes in their operations such as using more part-time and seasonal workers than before. Along with increased globalization of product manufacturing and services, American workers are having greater difficulties in having their wages increase or even keep pace with inflation. The Great Recession gave employers the excuse to also make greater use of robotics, advanced technology, the internet of things, and artificial intelligence in order to make products and provide services at a cheaper price, lower cost, and lesser number of workers. Many economists and policymakers are concerned that this is the start of a long-term trend that will see the number of workers further diminish, not only among skilled and unskilled, but also with the need for college educated staff and in paying higher wages.

Failure of the Phillips Curve: Traditionally, the reason to explain the relationship between unemployment and inflation has been the Phillips curve. Simply put, if the unemployment rate is down, then inflation should go up due to a lack of workers. If employers cannot find workers, they will have to pay more for new ones or to their existing workers and thereby causing inflation to increase since prices for goods and services will eventually increase. But this has not been the case. In fact, inflation is down and the Federal Reserve Bank is hoping for an uptick in inflation in order to show that there is some economic growth. Employers see no need to hire more workers nor to give their existing workforce a pay raise. In fact, employers are finding new ways to increase output at a cheaper cost. According to Moody’s Analytics, wage increases based on the current unemployment rate should be 3 to 3.5 percent. However, it is at approximately 2.5 percent. The odd thing that economists are seeing now and having a difficult time explaining is why both unemployment and inflation are low. The real inquiry should be whether this is the start of a new dynamic that may change the use of the Phillips curve or that the concept may soon need to be discarded since there is now a new normal regarding the relationship between wages, inflation, and unemployment.

Declining productivity: A serious problem that the American economy is experiencing is low productivity. Productivity is defined as output per hour of work. Traditionally, the relationship was that as output by workers increased so eventually would wages. But this has not occurred in recent time as pointed out by Jared Bernstein in an op-ed piece for The Washington Post in September 2017. He stated that productivity has been growing at 50 percent of its historical rate which means slower economic growth and lesser wage increases. According to a January 2015 report by the EPI, between 1948 and 1973, productivity was up 96.7 percent and hourly compensation was up 91.3 percent. However, between 1973 and 2013, productivity was up 74.4 percent and hourly compensation was up 9.2 percent. The big question is whether productivity can increase if wages also went up. Economists are trying to find the reasons why it is not occurring presently.

How low can it go?

The deep concern is that workers are not earning enough to make ends meet and that the United States can actually be seeing the shrinking of the middle class. Without a substantial number of workers earning a livable wage, there will more than likely be a disincentive for people to work. If so, then the American economy will contract in next ten to twenty years. Globally, if the United States is to compete, then a livable wage should be considered an important part of the mix. For example, in 2017 established economies such as Germany with a 2.2 percent real salary wage growth, Japan at 2.1 percent, India at 4.8 percent, and China at 4 percent far surpass the United States at 1.9 percent.

Workers are finding it more difficult to make ends meet and being able to fulfill such goals as owning a home. As reported in December 2017, home prices in the United States climbed 6.2 percent from 2016 as demand from potential buyers increased. Cities such as Seattle, at 12.7 percent, and San Diego, at 8.1 percent, have seen substantial growth in home values. But this trend may soon be reversed if wages for American workers do not increase over time.