By Dr. Ghulam Nabi Fai

If we were to judge the UN based upon its history of involvement in efforts to resolve international conflicts, the simplest answer is that it has been an enormous failure. The UN of course is a far more complex organization whose work covers such a wide range of activities that conflict resolution is really only a small aspect of its work. Nevertheless, if we consider the fact that its fundamental mission in being created was to be a means of preventing global catastrophes like the Second World War, then conflict resolution would have to be considered Job One. In addition, the word “conflict” in the phrase “conflict resolution” was defined as conflict among or between sovereign nations. As Chapter I, Article 2, stipulates, ” Nothing contained in the present Charter shall authorize the United Nations to intervene in matters which are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state or shall require the Members to submit such matters to settlement under the present Charter;”

Yet, curiously, in complete violation of this rule, one of the first significant acts of the UN occurred on November 29, 1947, to partition the state of Palestine into two states, a country which clearly was not in conflict or at war with any other. The partition plan ironically not only did not prevent war but in fact provoked a war between the newly created Israel and its neighbors, a conflict which has now gone on for 69 years with no resolution in sight.

Another great cause of failure was the Cold War involving the U.S. and the Soviet Union. From the very beginning until 1971, the Soviet Union vetoed Security Council resolutions a total of 81 times. A single veto within the Security Council virtually nullified any further action on a resolution. As authors Karen A. Mingst and Margaret P. Karns stated in their book, The United Nations in the Post-Cold War Era, “Thus, from 1945 onward, the United States generally supported the UN and its agencies broadly as instruments of its national policies. The United States utilized the UN and its specialized agencies to create the broad outlines of institutions and rules compatible with its interests.” These interests were frequently in competition with the interests of the Soviets.

When Mikhail Gorbachev assumed power in 1985, the need for rejuvenating the Soviet economy was at an all time high, and a gradual evolution began in the Soviet Union’s attitude toward the UN. Gorbachev saw the symptoms of current problems. As Rochester wrote, “The new Soviet view of the world was accompanied by a new view of the United Nations in particular. It was the UN that was to be the central international framework Gorbachev had in mind.”

Until 1965, the U.S. voted as a percentage with the majority of members but then gradually began a descent to the point where, by 1990, it was voting only 10 percent of the time with the majority, while the opposite occurred with the Soviet Union. With decolonization around the world, new members were being added to the United Nations, reducing the influence of the United States. The UN began with only 51 members but by 2011 with the addition of South Sudan, it had grown to 193. The roles between the two nations seemed to switch after 1970 until 1986 with the U.S. vetoing five times as many resolutions as the U.S.S.R.

Counted among the greatest failures of the UN is Srebrenica, a town in eastern Bosnia only ten miles from the border of Serbia, which came under attack by the Serbs in July 1995 during the Bosnian war. Although U.S. and British officials knew several weeks in advance that the Serbs intended not only to attack the village but also intended to separate all the men and boys from women and children and kill them, they did nothing to protect them. UN forces were not reinforced. No plan to evacuate them was made. The official policy was to allow the Serbs to take the town because it had been surrounded by Serb forces and was considered indefensible, despite being guaranteed as a “safe zone” by the UN. More than 8,000 men and boys were slaughtered in a matter of days.

In 1994, a far worse genocide occurred in Rwanda when close to a million Tutsis were slaughtered by Hutus. The UN knew that this was going to occur in advance and yet and allowed massive genocide to occur and did not block it. As an article in the Telegraph points out, ‘A 1999 inquiry found that the UN ignored evidence that the genocide was planned and refused to act once it had started. More than 2,500 UN peacekeepers were withdrawn after the murder of ten Belgian soldiers. In one case, the peacekeeping forces deserted a school where Tutsis were taking shelter – hundreds of people inside were immediately massacred.”

It is extremely difficult to understand such policy without considering the objectives of the corporate interests in neighboring DRC, or the Democratic Republic of Congo, considered one of the richest countries on the globe with more than $24 trillion in natural resources — diamonds, gold, copper, rubber, cobalt, and many other minerals. Following this massive slaughter, Paul Kagame, a Tutsi, called by the New York Times as the “global elite’s favorite strongman,” was then supplied with money and weapons by two permanent members of the UN to stage an invasion of Rwanda, which the genocide justified, and retake the country.

In addition, Kagame began supporting a rebel group in Congo called M23. As National Geographic points out, “The Security Council was embarrassed by the M23’s success in 2012, so the following March it passed Resolution 2098. Amid the predictable bromides—”Reiterating deep concern regarding the security and humanitarian crisis in North Kivu due to ongoing destabilizing activities of the 23 March Movement (M23) and other Congolese and foreign armed groups”—2098 contains one radical provision: It called for the creation of a so-called Force Intervention Brigade of UN troops. The brigade’s purpose is not peacekeeping but rather “peace enforcement.” If the semantic distinction is slight, the difference on the ground is significant: Peacekeepers only protect civilians; peace enforcers can attack the belligerents who threaten civilians. It was the intervention brigade that helped Congolese troops beat the M23.”

The resolution is highly controversial because the UN has always regarded its role as neutral and defensive in nature. It is however an approach to conflict we are likely to see more often in the future when the UN is called upon to resolve conflicts.

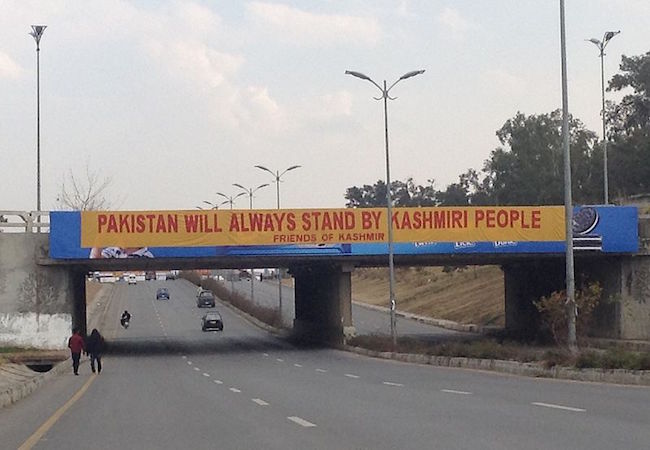

In context, Kashmir cannot be ignored, perhaps for no other reason than the conflict there has gone on for 69 years and seems destined to continue as long as the Indian armed forces continue to occupy the region. The potential for genocide is very real and massive killings have already occurred in the past. The tens of thousands who have been killed along with vast human rights abuses seem to go on without end. This past summer’s tragedy of violence was just another episode in the long drama that has been witnessed. The UN high Commissioner on Human Rights who spoke on September 13, 2016 during the opening of the Human Rights Council in Geneva, said in response, “We had previously received reports, and still continue to do so, claiming the Indian authorities had used force excessively against the civilian population under its administration…I believe an independent, impartial and international mission is now needed crucially and that it should be given free and complete access to establish an objective assessment of the claims made by the two sides.” Of course the Indian government continues to ignore such calls for investigation, because it believes that such ruthless tactics are the only way to deal with opposition to its policies. Such policies are almost a guarantee that yet another great tragedy in the UN’s history will occur.

Nevertheless, The Kashmir dispute has an international dimension because it has the sanctity of the UN Charter and UN Security Council resolutions and has become a big hurdle or obstacle in the growth and stability of both India and Pakistan. The unresolved conflict over Kashmir threatens the international peace and security of the world. It is far past time for the UN to take forceful action in order to restore peace to Kashmir. Perhaps Resolution 2098 ought to be reviewed as an option to consider in dealing with this problem, because nothing else to date has worked. It’s time for the UN to restore the faith of common people that it is an agency that can live up to its bold charter and mission of bringing peace and stability to the world.

Dr. Ghulam Nabi Fai is the Secretary General of World Kashmir Awareness