By Dr Subhan Ullah

After several years of budgetary constraints and recent austerity measures, 16 Pakistani universities have finally joined the Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2021 list. Quaid-e-Azam University, Islamabad and the recently established youngest institution, Abdul Wali Khan University, Mardan have been ranked between 501–600 globally, while COMSATS University ranked between 601–800. Other highly ranked Pakistani Universities included: Lahore University of Management Sciences, National University of Sciences and Technology, University of Peshawar, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, Government College University Faisalabad, amongst others. The Times ranking criteria includes an assessment of teaching, research, citations, industry income, and international outlook. Universities need to be excellent in all these metrices to achieve and sustain highest international ranking. The bureaucracy and documentations involved in submitting and compiling the data for the ranking process is cumbersome on behalf of the participating institutions. Volunteering to participate in such ranking exercise will certainly encourage more Pakistani universities to be reflected in similar ranking in the near future, and, would create a healthy educational competition between public and private sector universities in Pakistan.

Although global comparison of Pakistani universities would draw some unrealistic expectations and conclusions — an apple-apple regional comparison would make a better sense in assessing the overall quality of teaching, research, employability, and industry engagement. This extraordinary achievement certainly needs to be celebrated by the students and staff in these universities. Unfortunately, the mainstream private electronic media in Pakistan did not provide adequate coverage to promote this significant international achievement of Pakistani Universities. But, let us examine what 501–600 global ranking means in terms of global comparison? Some of the known global institutions in the 501–600 Times global ranking also included: Bond University (Australia), Dublin City University (Ireland), University of Hull (UK), University of Lincoln (UK), University of West of Scotland (UK), University of Waikato (New Zealand), University of Strasbourg (France). These institutions in the developed world receive strong financial support from their regional and national governments and are also able to generate funding through tuition fees by attracting local, and a vast majority of international students. In return, these higher educational institutions support the local economy by creating jobs and attracting foreign exchange, and contributing to the economic growth and GDP. Just as an example, Universities UK Report on the ‘The impact of Universities on the UK Economy’ shows that between 2011—2012, the UK higher education sector made a substantial contribution to economic activities by generating over £73 billion of output (both direct and indirect effects), and, the employment opportunities provided by the universities (757,268 full-time jobs) accounted for 2.7% of all UK employment. This shows that in addition to direct export earnings the higher education sector can boost the economic fortune and social well-being of the local community — where these universities operate.

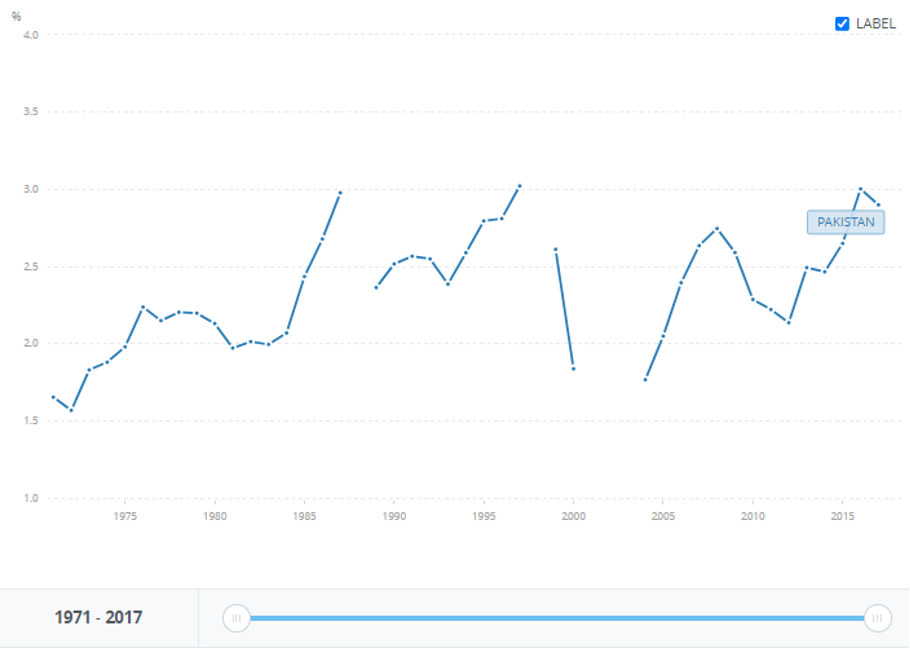

To develop a world class sustainable educational infrastructure, Islamabad needs substantial allocation for education in the federal budget, followed by an effective monitoring programme to assess a unified delivery of curriculum in all the provinces. The World Bank data reported in figure 1 shows approximately 3% of GDP is spent on education in Pakistan (this includes primary, secondary, and higher education).

Approximately 3% spending on GDP is not very encouraging compared to spending by smaller countries in the same geographical region (Bhutan — 7.226%, Nepal —5.518%). In the developed world, Norway, Iceland, and Sweden spend around 7.912%, 7.658%, and 7.569% respectively on education. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal number four requires member countries to ‘ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all’. Higher spending on education would signal a country’s commitment and seriousness in tackling socio-economic issues, including inequality, poverty, and equitable access to education.

Sadly, however, the international students’ representation in Pakistani universities is not very encouraging. The National University of Sciences and Technology has reported 4% international students, followed by University of Engineering & Technology (UET) Lahore (3%), University of Peshawar (2%) and Lahore University of Management Sciences (2%). There is indeed a great potential to further improve international students’ representation in Pakistani universities. This is an area which can improve the soft image of the country, and, can be a great source of foreign exchange for Pakistan. As a former student of the University of Peshawar back in 2002, we were so pleased to see a diverse range of international students (from Asia, Middle East, and Africa) on the premises of the University of Peshawar. Unfortunately, the security situation between 2002 and 2014 adversely affected international travel and tourism in Pakistan. As security situation in Pakistan has improved in the recent past, it is the right time for the government to explore alternative avenues of economic activities in a post-Covid world.

In the changing regional geo-political environment, education and knowledge exchange activities can be used as a foreign policy tool in advancing national economic interests. For example, China Scholarship Council (CSC) has recently implemented this approach by awarding hundreds and thousands of fully funded undergraduate and postgraduate (MSc, PhD level) scholarships to students from countries participating in the China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). So far, this initiative by the Chinese government has been proven very instrumental in promoting Chinese language, culture and the ‘global image’ of China in 71 BRI participating countries. Given the relatively lower cost of education and living, Pakistan can also afford to offer thousands of fully funded scholarships to international students. At the moment, Pakistani universities are heavily relying on financial support and funding from provincial and federal government. The 18thConstitutional Amendment in Pakistan offer greater autonomy to provinces, and each province has an opportunity to allow further financial autonomy to HEIs, so that they can manage their financial issues, and independently market their rankings and reputations in attracting overseas students. Finally, overseas Pakistani embassies can also play a more proactive role in cascading the educational achievements, rich cultural heritage, linguistic diversity, and, more importantly the beautiful landscape of northern Pakistan. Doing so, Pakistan can effectively achieve the first two key objectives of its foreign policy by portraying the country as a ‘dynamic, progressive, moderate, and democratic country’, and such dynamic foreign policy measures will help in ‘developing friendly relations with all countries’.