The terror attack that killed 12 people in Paris on Wednesday will have come as little surprise to Europe’s police and intelligence services. For months, they’ve regarded the prospect of a mass killing in Europe by isolated gunmen or small groups of Islamist terrorists as a question of when rather than if.

France has been a particular target. Officials there say hundreds of French Muslims who are believed to have gained military experience fighting with radical groups in Syria and Iraq.

Calls from radicals to attack civilians in France have multiplied following French military action against Islamist militants in West Africa and the participation of French warplanes in US-led airstrikes against the so-called Islamic State group in Iraq.

President Francois Hollande acknowledged the scale of the danger when he visited the offices of satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo where journalists, cartoonists and police officers were gunned down by two masked men shouting “God is Great” in Arabic.

“We are in an extremely difficult moment. Several terrorist attacks have been thwarted in recent weeks,” Hollande told reporters. “We know we are under threat.”

His Prime Minister Manuel Valls warned just before Christmas that France had “never before faced such a great danger in terms of terrorism.”

Wednesday’s shooting is the deadliest suspected Islamist attack on French territory and is sure to crank up fear in a country already tense after a series of recent incidents.

In 2012, Mohammed Merah killed three children and a teacher at a Jewish school and three French soldiers during a shooting spree in southwest France.

Another French Muslim, Mehdi Nemmouche — who is believed to have fought in Syria — is facing trial for the deaths of four people shot at a Jewish museum in Brussels, Belgium, last May.

Extra troops have been deployed in the streets since last month after pre-Christmas attacks in three cities, which included vehicles driving into shoppers and police officers wounded by a knife-wielding Muslim convert.

The authorities had sought to allay public concerns by characterizing the December attacks as the acts of disturbed and isolated individuals. That drew wrath from the far-right National Front opposition party which accused the government of minimizing the threat from Islamist terrorists.

Although Charlie Hebdo is a left-wing publication that frequently savaged National Front leader Marine Le Pen, many will see Wednesday’s attack as vindicating her concern.

Le Pen is already riding high in opinion polls after feeding off widespread unease among French voters over perceived threats to the country’s social and economic models from global trade and the euro-zone debt crisis, as well as worries over immigration and the influence of Islam.

Hollande declared Thursday a day of national mourning and was quick to appeal for unity after the attack amid worries it could feed into growing Islamophobia.

“Our greatest weapon is unity, the unity of all citizens to face up to this challenge,” the president told the nation in a televised address. “We must rally together, then we will win.”

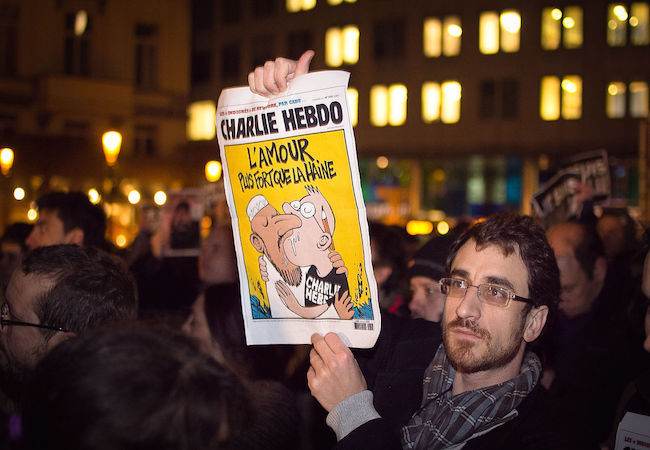

As night fell, citizens in Paris and in cities around France responded to the murders by gathering in huge silent crowds. Many waved pens as a symbol of media freedom, or carried signs bearing the slogan “Je Suis Charlie” (I Am Charlie).

Against that backdrop, rights groups fear Wednesday’s attack could fuel intolerance against Western Europe’s largest Muslim community. Muslims — most with roots in former French colonies in North Africa — are estimated to represent between 5 and 10% of the population.

“This type of tragedy will only strengthen the Islamophobia which has developed during the past couple of years,” Jean-Michel Delambre, a cartoonist with a rival paper who was friends with many of Wednesday’s victims at Charlie Hebdo, told Nord Littoral newspaper in northern France.

“I fear it will reinforce the current climate of hate and division that is rife in France.”

Ironically the attack on Charlie Hebdo — apparently in response to the paper’s frequent mocking of Islamic fundamentalism — came in a week where its cover lampooned one of France’s leading authors Michel Houellebecq, who faces accusations of encouraging Islamophobia in his new novel.

The book “Submission” which was published Wednesday has created a furor for depicting a France in 2022 with a Muslim president who imposes conservative Islamic rule.

It comes on the heels of the runaway success of “The French Suicide,” a nonfiction work by journalist Eric Zemmour, who claims national identity is being undermined by such factors as immigration, feminism and gay rights. He advocates deporting Muslims to avoid a civil war.

Although both books have been denounced as fear mongering and inciting hate — they currently sit in first and second place on the bestseller list of Amazon’s French site.