Deficits as far as the eye can see

By Arthur S. Guarino

The Trump Administration must deal with a financial problem of its own making: The Federal Budget deficit. Based upon the Trump administration’s own budget projections into the year 2030, the Federal Budget will be in the red even with a growing macroeconomy. A key concern is the long-term implications for these budget deficits.

With the release of the Trump Administration’s budget, it is projected that deficits will prevail until 2030. Deficits, according to economist John Maynard Keynes, are tolerable if the macroeconomy is in a recession or a depression since government should go into debt to help revive the nation’s economic situation. But the Trump Administration in its budget proposal is not projecting an economic slowdown nor a recession. The Administration projects that the American economy will keep growing. But the Trump Administration is not concerned in the least about budget deficits when it should be worried about the long-term implications of such shortfalls. The sadder part is that the American public and the Congress does not seem concerned about this potentially severe problem either.

Current Budget Deficit Situation

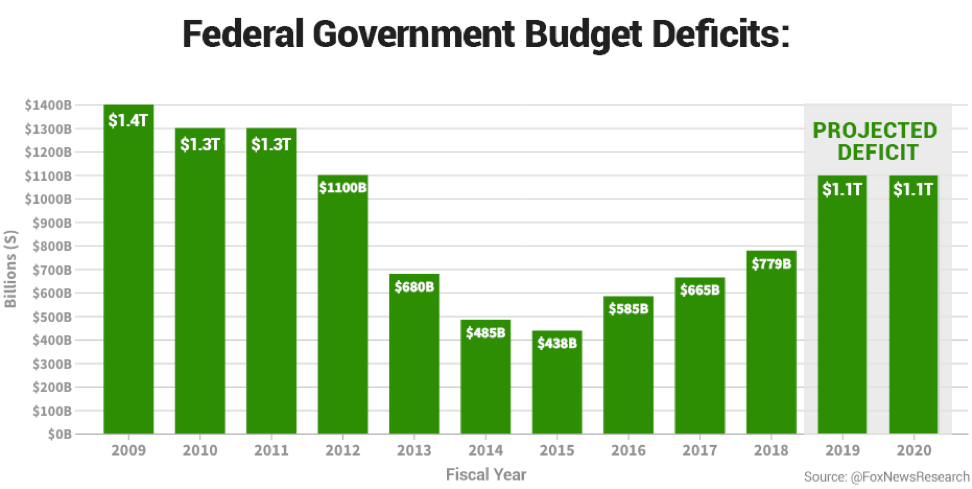

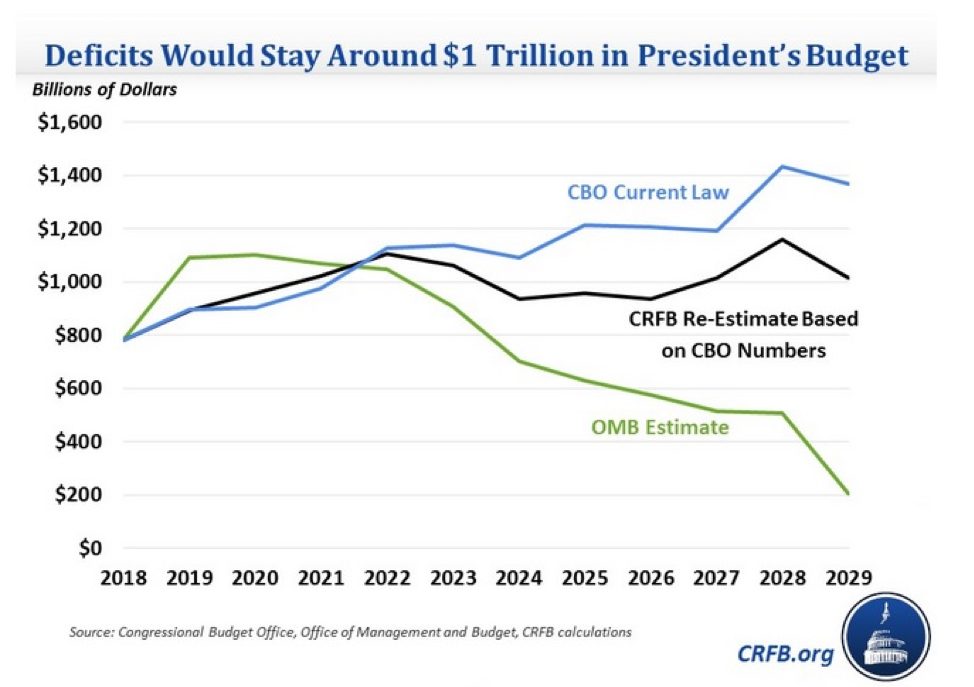

Using the Trump Administration’s recent budget proposal, for each year from 2019 to 2022, the federal budget deficit will be $1.1 trillion for each year. While the Administration is projecting that from 2023 to 2029 the budget deficit will average a little over $577 billion annually, the total amount of the deficits for the next decade will be $7.2 trillion. This means that the federal budget deficit will be $725.9 billion annually from 2020 to 2029. The Trump Administration is also projecting 3 percent economic growth from 2020 to 2029 while the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) is projecting under 2 percent growth annually for the same time period. This extra percentage of economic growth is expected to save the Trump Administration more than $3 trillion. However, this does not take into account extra spending in case of a recession or economic slowdown.

On top of this, the Trump Administration is projecting that the National Debt will rise from $18.087 trillion to $24.77 trillion in 2029. This translates into an annual increase in the National Debt of 3.7% in order to pay for the federal budget deficit. The Administration is also projecting that the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) will rise from $22.41 trillion in 2020 to $34.727 trillion in 2029. The Trump Administration is estimating that the nation’s economy will grow at an average of 5.5% per year in order to help the United States stay ahead of its National Debt situation. But these are only projections and whether they actually come to fruition is really anyone’s guess.

But for the Trump Administration’s current federal budget proposal there have been economic and financial analysis that have placed these figures under critical scrutiny. The CBO has stated that if the Administration’s budget proposal were enacted as planned it would result in budget deficits of $2.7 trillion greater than projected by the White House budget office. The CBO predicts that federal budget deficits will equal almost $10 trillion from the years 2020 to 2029. TheTrump Administration is only projecting budget deficits equaling $7.3 trillion. To make matters worse, the Trump Administration is projecting that it could reduce the federal budget deficit by $4.1 trillion over the next ten years but the CBO contradicts this statement by predicting that deficits would only be reduced by $1.5 trillion.

What is not helping the Administration with the deficit is the Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA) passed in December 2017. The Trump Administration pushed the TCJA as a way to stimulate an already growing U.S. economy and to cut taxes. The Administration felt that by stimulating the American macroeconomy this would result in massive job creation and ultimately more tax revenues. However, this is not occurring. For example, in February 2019 the U.S. government had its largest monthly budget deficit in American history due to a reduction in collection of tax revenues while government expenditures soared to new heights.

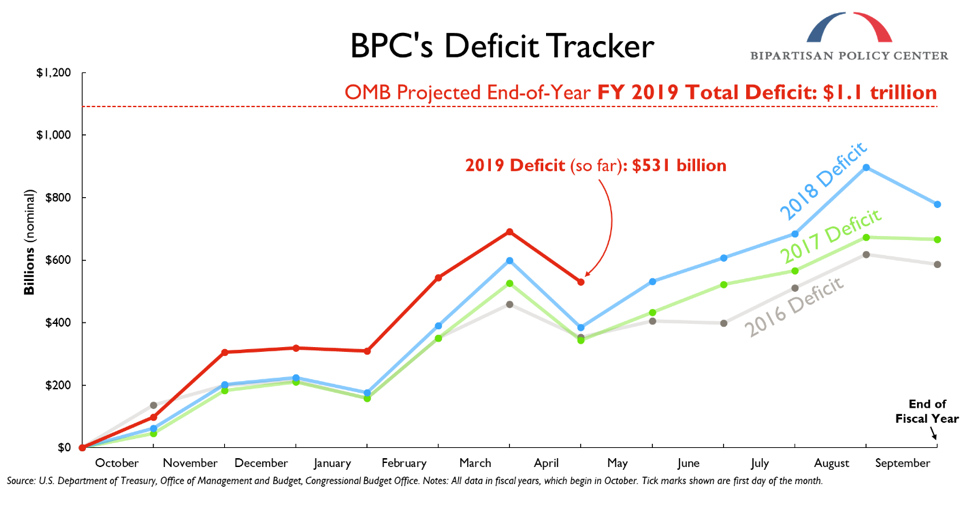

In February 2019, Federal government expenditures were $401 billion while revenues amounted to $167 billion. Even though tax receipts are usually weak in the month of February since American taxpayers are looking for refunds, for February 2019 tax collections were lower than the amount recorded in 2016. This could be part of a long-term trend because the CBOannounced in its latest economic forecast that, “Over the coming decade, deficits. . .[will] fluctuate between 4.1 percent and 4.7 percent of GDP, well above the average over the past 50 years,” averaging 4.4 percent annually from 2020 to 2029. The CBO report should be of deep concern since in the past 50 years, the annual federal budget deficit was, on average, only 2.9 percent of GDP. The situation only seems to get worse: for the first seven months of fiscal year 2019 the U.S. budget deficit increased 38 percent.

Why Budget Deficits Matter

It has been stated in the past, that budget deficits do not matter. That is, they have no impact on the macroeconomy, the national or global economic health, or to such economic components as job growth. While so far that may be holding true, the future economic and financial impact could be another story. There can be several areas in which federal budget deficits will impact the American economy:

Increase in the National Debt: The National Debt has seen significant increases since the end of World War II and under the Trump Administration budget proposal it will continue to grow. The problem is that as the United States continues to borrow money, it must pay back both the principal and interest. This is money that could go to such areas as housing, rebuilding the nation’s infrastructure, job creation, and basic and applied research. But if money continues to go toward repaying the National Debt, other areas that need the funds to help America become competitive globally will lag behind and the U.S. economy could shrink in the long-term. There is only so much that businesses and households can put into the American economy to help it grow. An ever-increasing National Debt means depriving funds for other aspects of the American economy that could have a better return on investment in the next 50 to 100 years.

Interest payments will increase: In order to pay the National Debt, lenders are depending not just on getting their original principal returned but also the interest. In the entire history of the United States, it has never reneged on its debt. The United States, in good times and bad, in depressions and boom periods, has always made good on its debt obligations. Investors or lenders from the United States and abroad can always count on getting their principal and interest on whatever amount of money they have lent to the Federal government. But the problem will eventually occur that interest on the National Debt will be substantial in the future. According to the Trump Administration’s recent budget proposal, the net interest to be paid on the National Debt for the years 2020 to 2029 will be $7.154 trillion or $71.54 billion annually. However, in fiscal year 2018, the federal government has spent more money on interest payments than on departments such as transportation, veterans’ benefits, and administration of justice. But for fiscal year 2019, the amount of interest to be paid back on the National Debt will exceed the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Supplemental Security Income (SSI), and unemployment benefits. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget reported in 2019 that interest payments on the National Debt will increase from $325 billion in 2018 to $928 billion by 2029. It is not unrealistic to see interest payments reach $1 trillion annually if tax cuts increase, tax receipts decrease, and government expenditures continue to climb. This will also mean that the Federal government will make the difficult decision of cutting spending for various programs in order to possibly balance the Federal budget and keep its long-held reputation for meeting its debt obligations.

Higher interest rates: With the Federal government borrowing more due to being able to cover the higher debt amount, this will mean enticing lenders to lend at a higher interest rate. Lenders or investors will need some type of enticement to lend the Federal government more money as the National Debt increases over time. This means that interest payments will increase and that unless the interest is paid for, the Federal government will need to borrow more money to pay the interest. It is a vicious cycle that could potentially keep increasing over time with interest rates going up and the National Debt doing likewise. Even if there is a recession or major economic slowdown in the United States, while interest rates will decrease, the amount of the National Debt will increase since the Federal government will borrow more in order to sponsor programs that will pour money into the macroeconomy and help get it back on the road to economic growth. But the bottom line is that lenders or investors will only lend to the Federal government if they are motivated by higher interest rates in order to be compensated for potentially higher risk.

Crowding out effect: If interest rates on U.S. debt obligations rise, then lenders or investors will forego private investments. The problem here is that private investments in corporations may not be able to borrow money at higher rates since it may not be financially feasible. If the U.S. government raises interest rates on its debt offerings, such as Treasury bonds, in order to attract lenders or investors, private and public corporations may not be able to match these rate increases. In this case, debt offering by businesses may be cost prohibitive and stymie any possibility of borrowing money for research and development projects, business expansion, or hiring more workers. The Federal government should not be in direct competition with businesses for financial capital so it can pay off or maintain its level of debt. Businesses need to borrow money as one way to ultimately help expand the U.S. economy in the long run. Instead, the crowding out effect could prohibit the U.S. economy from experiencing long-term growth.

Does the American public really care?

While the Federal budget deficit is a real problem, the important question is whether the American public really cares? If the average American citizen were asked the significance of the increasing Federal budget deficit, how many would be aware of its financial and economic implications? How many would know how much the Federal budget deficit really is or how it achieved the level it is currently at? Most Americans are too concerned about having a job at a livable wage, putting food on the table, keeping a roof over their families’ head, being able to pay for their child’s college tuition, and affording medical care. The Federal budget deficit, and subsequentially the National Debt, is a very real problem with major long-term economic and financial implications. But the real problem is that too many Americans either do not care or feel that it really does not affect them at all. They will come to realize that this is a wrong assumption.

*This post contains affiliate link(s). Click here for Affiliate Disclosure.