By Joanna Kenty, Temple University

In the wake of his acquittal from impeachment charges, President Donald Trump has been trumpeting his power and firing government officials who had testified against him.

Can he do that?

It’s an important question, in light of an argument his legal team used to defend him in his Senate trial. Alan Dershowitz argued that any act by a president seeking reelection was inherently in the national interest. That claim sparked critics’ latest round of allusions to dictatorship, authoritarianism and monarchy. One Democratic senator even called Trump’s acquittal “the coronation of President Trump as king.”

I am a scholar of Roman history and rhetoric, and these comments reminded me of a moment more than 2,000 years ago, when Mark Antony, one of the most prominent and powerful politicians in the Roman Republic, offered the nation’s elected leader, Julius Caesar, a crown.

What happened next shifted the course of history – and shortened the course of Caesar’s life.

A brief history of Rome

According to legend, the Romans had banished their last king in 509 B.C., when they founded the republic and vowed never to be ruled by kings again.

Instead, Roman citizens elected magistrates, led by two consuls, in a republic which offered a model to America’s own Founding Fathers. Sometimes, in times of crisis, they elected a “dictator” to wield sweeping powers (a sort of martial law), for a term of six months, or until the emergency had been resolved and the government could go back to normal.

In the first century B.C., military commanders like Marius, Sulla, and Pompey had upset the equilibrium of this system, amassing extra-constitutional powers with the support of the masses. But Julius Caesar took things a step further. In 49 B.C., he led his Roman army out of Gaul and across the Rubicon River into Italy, and was elected dictator. That kicked off three years of civil war. During the war, he was elected dictator again, for a whole year. Then again, for 10 years. Then in perpetuity, with no term limit. He was elected consul too, with his right-hand man Mark Antony as his co-consul.

‘Where did you get the crown?’

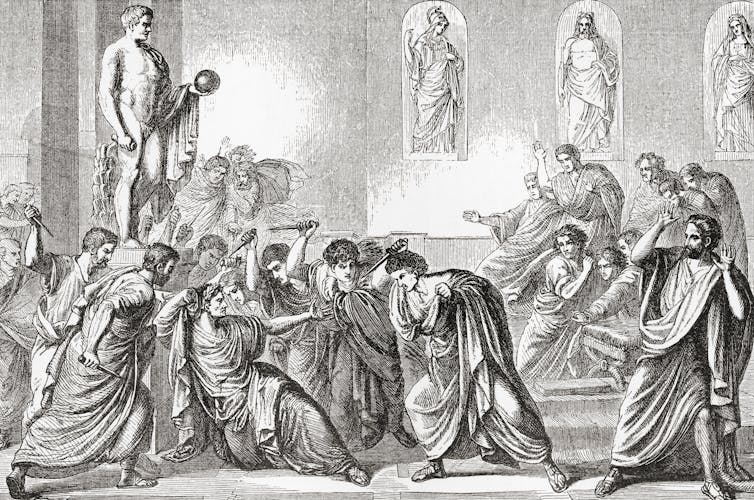

On Feb. 15 in 44 B.C., Caesar, now dictator for life, was back in Rome. He was sitting on a stage watching the celebrations of a purification festival called the Lupercalia. At one point, Caesar’s co-consul Mark Antony approached Caesar’s stage.

Cicero, a lawyer and leading politician of the time – and one of the greatest Roman writers – describes what happened next, as if he were addressing Antony:

“Your co-consul [Caesar] was sitting on the speakers’ stage, wearing the purple toga of a triumphant general, seated on a golden chair, wearing a laurel wreath of victory. You [Antony] climb up, approach his chair … and show him a crown.

“The entire forum groaned. Where did you get the crown? You didn’t just find it lying there, you brought it from home, a premeditated and carefully planned crime. You put the crown on Caesar, and the crowd wailed; he rejected it, and they cheered. You criminal, you advocated for kingship and wanted to make your co-consul into your master, you were the only person to test what the Roman people could put up with and tolerate. …

“Caesar even ordered an inscription in the official record: ‘At the Lupercalia, when the consul Mark Antony offered the kingship to Gaius [Julius] Caesar, dictator for life, by the order of the people, Caesar said that he did not want it.’”

Power by any other name

According to Cicero (a slave owner himself), Antony wanted Caesar to be more than just a consul and dictator for life: He wanted Caesar to be a king. Antony wanted the Romans to be subjects rather than citizens, as slaves are to their master. No glory was too great for Caesar, in his eyes.

But Caesar said he didn’t want that power. Historians are unsure of what was really happening in that moment at the Lupercalia. Maybe Caesar didn’t want to be a king, and devised Antony’s stunt as a way to demonstrate to the people that he respected the republic.

Or maybe he did want to be a king, but the crowd’s reaction changed his mind. Maybe Cicero was just being paranoid or politicizing the event.

If some people wanted Caesar to be king, and everyone thought he had the powers of a king, maybe Mark Antony thought he was just formalizing what everyone already knew: that the republic was no longer subject to the rule of law or the magistrates, but to Caesar.

But claiming new powers with no expiration date was different from claiming the title of king: The title was more symbolic, and maybe more dangerous, because it would represent a judgment about what kind of power Caesar thought he had over Rome. Becoming king wouldn’t have meant just changing the label of the system of government – it would have shifted the basis of Romans’ national identity. They were citizens of a republic, owners of a “commonwealth” (in Latin, “res publica”), free and self-governing – in name, if not always in reality. To be ruled by a king would be giving up that identity.

A threat of tyranny

Ultimately, it didn’t matter what name Caesar put or didn’t put on his power. A month after he refused the crown, Brutus, Cassius and their co-conspirators murdered Caesar in the Roman Senate because they believed he had become a tyrant.

To them, one-man rule by any name was unthinkable, a betrayal of Roman values and the death of freedom. Mark Antony gave the assassins amnesty in exchange for keeping his own power, but later drove them out of the city and seized power as great as any Caesar had held – though it was held jointly with two others, as part of the oppressive Second Triumvirate.

Caesar was clever, a gifted orator and writer, a fearsome military strategist with ambitious plans for Rome. Many Roman citizens seem to have been happy to give up whatever civil liberties they had to celebrate their heroic leader. After his death, they worshiped him as a god.

Perhaps, like some Americans today, some Romans hoped that authoritarianism would solve society’s ills. But to some Roman senators, the name of monarchy – represented by a symbolic crown – was worth dying for, and worth killing for.

Cicero describes Mark Antony as using the Lupercalia incident as a sort of test balloon, to see where the Roman people’s limits were. In a time when we’re inundated with breaking news stories and unprecedented scandals, it may seem silly to worry about names and labels. But in my view, it’s worth stepping back and looking at the big picture.

Is the political system working the way Americans think it is? Are they the free, self-governing citizens they expect to be? It’s not always clear when a new chapter in the history books begins, but a symbolic test in a public forum can reveal changes in what’s politically acceptable.

[Insight, in your inbox each day. You can get it with The Conversation’s email newsletter.]![]()

Joanna Kenty, Postdoctoral Faculty Fellow in Classical Studies, Temple University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.