By Jamil Maidan Flores

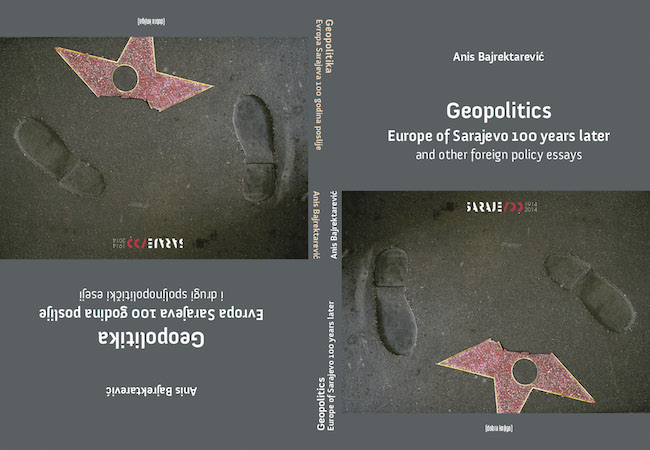

Prof. Anis H. Bajrektarevic recently launched a book titled, “Europe of Sarajevo 100 Years Later: From WWI to www.” Only Prof. Anis, I think, can write a book of that title, just as he’s the only intellectual I know who argues passionately that Google is the Gulag of our time, the prison of the free mind.

His editor tells us that in the book, Prof. Anis makes the case that the history of Europe, perhaps of the world, since World War I has been a history of geopolitical imperative. And that, in the face of climate change, the crisis that grips all of us is not really ecological, as it never was financial, but moral.

Prof. Anis is chairperson for international law and global political studies at the University IMC-Krems, Austria. I’ve been reading some of his recent writings. A native Sarajevan who now lives in Vienna, he doesn’t see one seamless Europe but several.

There’s Atlantic Europe, a political powerhouse that boasts two nuclear states. There’s Central Europe, an economic powerhouse. Scandinavian Europe is a little of both. And Eastern Europe that’s none of either. And beyond Eastern Europe, is a Europe-stalking Russia.

“Although seemingly unified,” he writes, “Europe is essentially composed of several segments, each of them with its own dynamics, legacies and political culture… Atlantic and Central Europe are confident and secure at one end, while Eastern Europe as well as Russia on the other end, (are) insecure and neuralgic, therefore in a permanent quest for additional security guarantees.”

The underachiever of the lot is Eastern Europe, and often the victim of Europe’s turmoil. It bore the brunt of World War II in the 1940s, suffered even more during the Yugoslav implosion of the 1990s, and again today in the Ukrainian civil war.

A fascinating part of Eastern Europe is its southern flank, the Balkans, where the US-led West and Russia are today engaged in a tug of war for influence. In here is the cradle of Western civilization, Greece, which is now in deep financial and economic trouble. If it’s not bailed out of its misery, it just might leave the euro-zone.

I haven’t come across Prof. Anis’s views on the consequences of a Grexit, or a Greek exit from the euro-zone and possibly also from the European Union, but many other thoughtful people have said a lot on this topic. Their views range from, “Oh, nothing much,” to, “This will be Armageddon.”

I side with those who say that if Europe doesn’t save Greece, it will itself be in need of saving. A Greek fall from the euro-zone will have a domino effect, which can happen in slow motion, over the years, but in the end will leave the EU a mere ghost of what it is today. Meanwhile, in its agony Greece could become Russia’s Orthodox altar boy, which would be anathema to the West.

And then there’s the Asian connection: China is already heavily invested in the port of Piraeus in Athens, the hub of Greek shipping and the gateway to Europe for China’s ambitious Maritime Silk Road project. Asean nations are stakeholders in that endeavor.

Meanwhile negotiations between Greece and its European creditors for a 7.2-billion-euro ($8-billion) bailout hang in the balance. Creditors and financial institutions demand fiscal reform measures that are bitter to Greece. We’ll know within days if there’s a deal or not.

Indonesia went through a similar ordeal in 1998 and has since recovered very nicely. So it’s too early to write off the Greek drama as unmitigated tragedy. And, in spite of Pope Francis, Europe isn’t an old woman who has fallen and cannot rise.

It’s a grand old man walking a tightrope between “cosmos” and “chaos,” two favorite Greek words of Prof. Anis.

Jamil Maidan Flores is a Jakarta-based literary writer whose interests include philosophy and foreign policy. The views expressed here are his own.

First published by Jakarta Post on June 29, 2015. Republished with permission of the author